Daniel “Rusty” Staub, 57, is more than just a baseball legend to New York firefighters and police. The ex-Met has been operating the New York Police and Fire Widows and Children’s Benefit Fund since 1985.

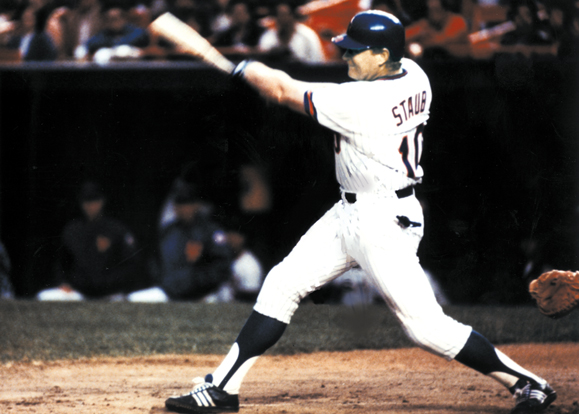

Staub, who hit 292 career home runs in 23 seasons with five different teams, including two different stints with the New York Mets, started the fund after reading a newspaper account of a police officer who was killed in the line of duty.

“We are the first line of defense for families,” he says from his home in Florida (Staub had to evacuate his apartment in downtown Manhattan on September 11). “Usually within 24 hours we have ten thousand dollars in the hands of the family, who don’t need the added burden of financial worries at such a sad time.” The Fund also makes a yearly payment to families, and it’s not just to offer financial support but “so they know that someone cares,” says Staub.

Staub knows firsthand what it’s like to lose a family member in this way. His Uncle Marvin, a motorcycle cop, was killed when Staub was a youngster, and he recalls how much hardship the family suffered later. “Back in the forties and fifties there was nothing in place to take care of the families,” he recalls.

Nicknamed Le Grande Orange, because of his bright red hair, Staub, who has been to Ireland many times, traces his Irish lineage through his mother’s dad, Alonzo Morton, who he says was a gifted tile-setter. “He was as Irish as you could get,” Staub recalls. “He liked a few drinks and he lived until he was eighty.”

The son of a schoolteacher, Staub grew up in a New Orleans neighborhood with the families of firemen and police, and he says he has a natural “affinity” for those in the public service.

His involvement with the NYPD began when he met Patrick Burns, a cop who worked with the 19th Precinct near Shea Stadium, when Staub first came to play with the Mets. “I would see Paddy on the street and say hello,” he recalls, “and occasionally I would talk to a problem kid for him.”

During that time Staub supported PAL (the Police Athletic League) and sought to improve the working conditions for police officers by supplying bulletproof vests. Amazing though it seems now, providing such protection was not the norm back then. “Until the big boys down town supplied vests [bullet-proof] we tied to ensure that every precinct had at least one vest,” Staub recalls. Through Staub’s initiative, the Detroit Tigers made a presentation of vests to the NYPD.

His involvement with the police department took an even more serious turn when he founded the New York Police and Fire Widows and Children’s Benefit Fund. He recalls how it happened. “I was in my restaurant one day in 1985 and I read a newspaper article on a police officer who was killed in line of duty. He left a couple of kids — the oldest was five. And I kind of got mad at myself that I hadn’t done more.”

Staub called up his old friend Patrick Burns.

“Paddy came along with Tom Reilly, then treasurer of the UFA [United Firefighters Association], and it was decided that we would start a benefit fund for the widows and children of police officers and firemen killed in the line of duty.

Staub and his organization have raised millions for the fund, and impacted thousands of lives. “When the fund started, we had 451 widows still alive, including the widow of a guy on the bomb squad who was killed trying to defuse that bomb at the World’s Fair,” Staub recalls.

Now, in the wake of September 11, the organization is raising money for the widows of those police and firefighters killed in the rescue mission at the World Trade Center. The Mets, with whom Staub has kept close connections, donated a day’s pay.

“On September 11, we lost 405 people including emergency service and Port Authority Police. And we now have two widowers in the group also,” Staub says. On June 18, the fund, now more important than ever, will hold their 17th annual picnic at Shea Stadium, and on November 19 they will host their 16th dinner in New York. ♦

Leave a Reply