An excerpt from Dennis Smith’s latest book.

℘℘℘

In the chief’s van, Chief Pfeifer hears the Manhattan dispatcher announce that a plane has gone into tower 1 of the World Trade Center. The chief reaches for the telephone.

“Battalion 1 to Manhattan.”

“Okay,” the dispatcher answers. It is John Lightsey who is working the microphone this shift.

“We have another report of a fire,” Chief Pfeifer says, calmly and resolutely. He knows these are public airwaves. “It looks like a plane has steamed into the building. Transmit a third alarm. We’ll have a staging area at Vesey and West Streets. Have the third-alarm assignment go into that area, the second-alarm assignment go to the building.”

“Ten-four,” Lightsey answers.

He next hears on the radio, “Division 1 is on the air.”

“Ten-four, Division 1. You have a full third-alarm assignment.”

Chief Pfeifer now knows that Chief Hayden is on his way. He and cChief Hayden have been colleagues for a long time, and he is glad this is the deputy on assignment today.

When he reaches the staging area and steps into the street, he sees a large amount of fire and white smoke lifting from the top of the building to the sky. Behind him, Jules Naudet follows with his video camera. Chief Pfeifer pulls his heavy bunker pants over his trousers, and steps into his boots. He puts his helmet on, a leather helmet painted over with white enamel, which has been the traditional style of the FDNY for more than a hundred years. His own has a large front piece that reads, in a large antiqued lettering: battalion chief. There is a shower of debris falling, and he runs through it into the building, straight through to the elevator control bank, where he sets up a command post. He notices that al the twenty-five-foot-high windows that surround the lobby, at least in this northwest section of the building, have been blown out, and people are walking through the frames. The windows were undoubtedly broken upon the impact of the plane, which means the building must have shook violently.

A maintenance worker runs to him, saying, “We have a report of people trapped in a stairwell on 78.”

“Okay, 78,” he answers. People have begun staggering through the lobby, badly burned, while others are running. The firefighters of Ladder 10 appear, as does an officer who reports to the chief.

“I want you to go to 78,” Chief Pfeifer says.

“What floor, Chief?” the officer asks. It is almost as if he does not want to register the floor number, anticipating the length of the climb, the weight of the equipment he has to carry, and the smoke and fire that will confront him there.

“Seventy-eight.”

Just then Chief Hayden arrives. The unspoken transfer of command is passed from Chief Pfeifer, even as they realize they are al in this together. The elevator control bank stands behind a five-foot marble wall, and Chief Hayden and Chief Pfeifer station themselves behind it. As firefighters report in, they speak to the chiefs as customers do over a high counter in a meat market. Civilians are running past the firefighters, leaving the lobby as firefighters are entering it. The firefighters move more deliberately, carrying equipment and hose, for they know they have to conserve their energy to ascend the highest building in the city.

Chief Hayden and Chief Pfeifer are very focused and exacting. Not a voice is raised in any discussion between firefighters and fire chiefs.

chief Bill McGovern of Battalion 2 joins them. About thirty firefighters have gathered, patiently awaiting assignment, hose and tools at their feet.

As their orders are issued they disappear into the building, and other firefighters appear, among them the men of Engine 10. In front of the elevator bank counter, the field communications unit begins to set up a portable command station consisting of a large suitcase-like piece of equipment on four legs, with a magnetic board where the list of entering fire companies can be logged. Just behind them, firefighters are dressing the windows, breaking off the dangerously hanging shards of glass.

Lieutenant Kevin Pfeifer and the men of Engine 33 arrive and report toChief Pfeifer. The chief seems surprised to see his brother now in front of him, for he knew that Kevin had put in for a couple weeks off, combining vacation days and trading of work tours with another officer, to study fro the upcoming captain’s test.

“The fire is reported,” Chief Pfeifer says, “on 78 or 80.” There is none of the normal joking between them. Kevin nods, needing no further information, and then the two brothers lock eyes together for a few moments of shared and worried concern before Kevin leads his men to the stairs. Their names can be read on their bunker coats as they depart: pfeifer, boyle, arce, maynard, king, evans.

Rescue 1 arrives with Captain Hatton carrying an extra bottle of air, followed by Tom Schoales and the men of Engine 4. A group of police officers passes through the lobby and disappears into the stairwell, all with masks, air tanks, and blue hard hats. They are carrying large black nylon satchels filled with their tools and ropes. These are members of the elite emergency service unit of the NYPD.

Chief of Safety Turi has also arrived and speaks with Chief Hayden.

Assistant Chief of Department Callan steps into the lobby and takes command, almost automatically. He speaks into his handy-talkie, “Battalion 7…Battalion 7..”

Captain Jonas and the men of Ladder 6 enter and speak momentarily with Chief Hayden and then to Chief Pfeifer. Just as they take their orders there is a loud crashing sound outdoors. Debris, some large and burning, showers down from the crash floors, hitting the ground with such force that pieces shoot into the lobby like shrapnel. Someone says, “I just saw a plane go into the other building.”

Tom Von Essen, the fire commissioner, appears, but no one goes to greet him. He is on the civilian side of the department, and his counsel will not be sought by the fire chiefs.

It is 9:03 a.m. All of the chiefs have radios to their ears, and they do not seem surprised by the news of the second plane. Maybe it is responsible for all the burning debris outside.

The fire commissioner walks over to the huddled chiefs and listens for a few moments, then moves away. A Firefighter from Rescue 1 is standing before the command post waiting for someone to tell him the location of his company so he can catch up with them. Another firefighter passes with a length of folded hose on his shoulder, ninety feet long and forty pounds .he field com firefighter says, holding a phone, “I have Battalion 2 here.”

Chief Pfeifer takes the line to speak to Chief McGovern, who has now gone up into the building. Chief Hayden says to an officer, “I have a report of trapped people up on 71.”

The deputy fire commissioners are now on the scene and are standing off to the side with the fire commissioner. The firefighters ofLadder 1 move to the command post, receive their orders, and then quickly advance into the building. Chief Hayden is talking in the middle of the group of fire chiefs when he is suddenly interrupted by a loud report, as if a very large shotgun has been fired. Startled, he turns toward the sound and realizes it has come from the impact of a falling body, the first person to jump on this side of the building.

An African-American firefighter nearby looks profoundly pensive as he moves to a wall and scans the lobby.

Deputy Commissioner Bill Feehan stops to assist a group of people in the lobby. One says, “Please take me out of here.” Bill Feehan was once the chief in the department, the highest uniformed rank, but today he knows that he too is on the civilian side. He directs them to proceed in the direction they are going, to keep moving, and reassures them. It is Commissioner Feehan’s way, to keep everyone reassured.

The fire companies keep stepping up to the command post, as orderly as in a parade. They stop briefly as their company officer speaks to one of the chiefs to receive instruction.

Few firefighters are in the lobby atone time now, for they are all quickly and methodically dispatched to their work, going up, up, as high as the sixteenth floor. all the while there is an incessant whistling from the firefighters’ Air Paks, the crashing of debris outside, and the frightful bang, bang, bang as the bodies begin to fall one after another.

Chief Hayden is in a discussion with the chief of safety.

“But,” he is saying, “we have to get those people out!” He doesn’t gesture, he doesn’t flail his arms, but the tension in his voice is noticeable . All the chiefs are by now beginning to appreciate the extent of the terrible scene above them, getting worse by the second.

Engine 16 comes into the lobby as more emergency police officers and EMTs move in and out of the building. A Probationary firefighter, his orange front piece denoting the short period of time he has served in the department, stands alone, waiting for his officer, looking ambivalent, as if he is trying to gauge the dangers that surround him. None of the firefighters remaining on the floor are talking among themselves. as they wait for their orders, every one of them exudes an undeniable apprehension, as if they suspect, each of them, that an almost certain doom faces this group. But for now, all they really know is that this is the toughest job they have ever faced.

A voice is heard, a chief’s command: “All units down to the lobby.”

There is another sudden crash and breaking glass as bodies continue to fall from the very top floors, ninety floors up, traveling at 120 miles per hour. The sound has become a part of the environment, and hardly anyone reacts to it.

A field com firefighter stands before the opened suitcase of the command unit. There is a telephone connected to it, and lined boxes with titles written across the open lid: staging area, address, alarms, r&r, control. In the boxes are white tags for the fire companies in both buildings.

Father Mychal Judge appears, in his turnout jacket and white helmet. He stands off to the side, his hands on his hips, careful to stay out of the way of the huddles. The loud whistling in the background is now coming in series of fours, “scheeeeee, scheeeeee, scheeeeee, scheeeeee.” The whistles come from firefighters’ alarm packs that are going off, what they call the personal alert alarm, designed to locate downed firefighters.

Yelling is the preferred form of communication who are not sharing radio waves. Police officers in shirtsleeves and men form the mayor’s Office of Emergency Management are all about, mostly on cell phones and handy-talkies. On a balcony above them a crowd of men and women moves forward in an orderly way. Where have they come from, a stairwell or an elevator? These are survivors. The bangs of the falling bodies in the plaza are now regular, and almost syncopated.

Father Judge’s lips move in silent prayer as four firefighters pass him carrying a Stokes basket. The Franciscan is so focused in his meditation, so completely one with his inner voice as it is connecting with God, that it appears he is straining himself and that the power of his prayer is outpacing the ability of his heart to keep up. Chief Pfeifer notices that the priest seems to be carrying a great burden in the midst of this disaster, and he is struck by his aloneness, praying so feverishly, like Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. Finally, a man goes over to Father Judge and shakes his hand. “I’m Michael Angelini,” he says. father Judge is pleased to see him, for Michael’s father, Joe, is a member of Rescue 1 and also the president of the department’s Catholic fraternal association.

“Ahh,” Father Judge says, “Your mother and father were recently at my jubilee celebration. I will pray for your family, Michael.” Father Judge taps him on the shoulder. It is the human thing. A handshake is not quite sufficient. Michael leaves the priest’s side, and Father Judge is again let alone with his prayers. He has no one to counsel, no one to console, no one to shepherd. It is only him and God now, together, trying to work the greatest emergency New York has ever seen. It is obvious that Father Judge is trying to make some agreement about the safety of his firefighters.

A Port Authority police officer in white shirtsleeves has the attention, momentarily, of the chiefs. chief Pfeifer tells a firefighter too write Tower 1 across a panel top where they are standing, the elevator control bank. Then Chief Pfeifer begins to call in his radio for 44, when a loud noise is heard, a new and odd noise, a rumble. No, it is a roar. ♦

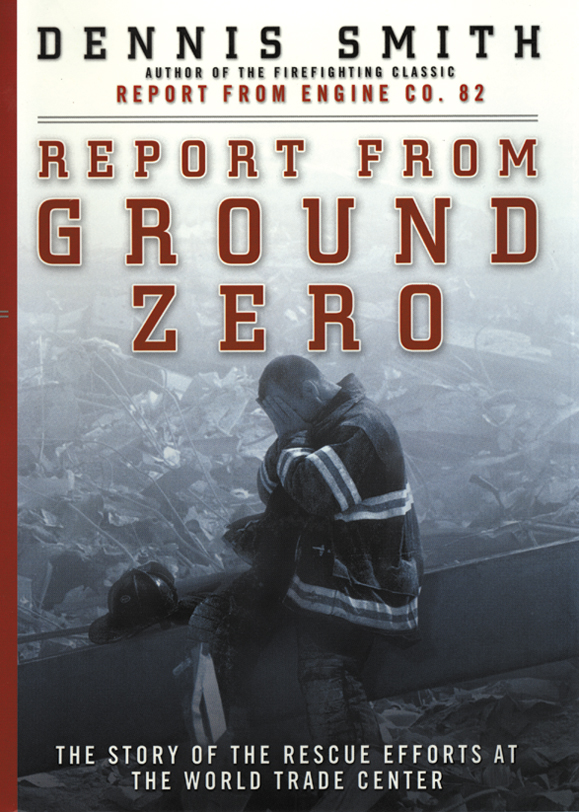

– From REPORT FROM GROUND ZERO by Dennis Smith.

Copyright © Dennis Smith, 2002. Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a division of Penguin Putman Inc.

Leave a Reply