A look at Warren Allen Smith’s Who’s Who in Hell.

Warren Allen Smith, whose great-grandfather was an Irish-American named Curran, has, with tongue firmly wedged in cheek, we suspect, compiled a 1200 page compendium with the fascinating title Who’s Who in Hell. One might think he’s rushing things a bit because the book lists atheists, humanists, naturalists, freethinkers, agnostics and others of that ilk who are still very much alive. If one labors under the delusion that all Irish are either militantly Catholic or Protestant, one is in for a bit of a shock, as the evidence presented in Smith’s tome shows that quite a few could easily be labeled as practicing non-believers, shall we say “the unfaithful.”

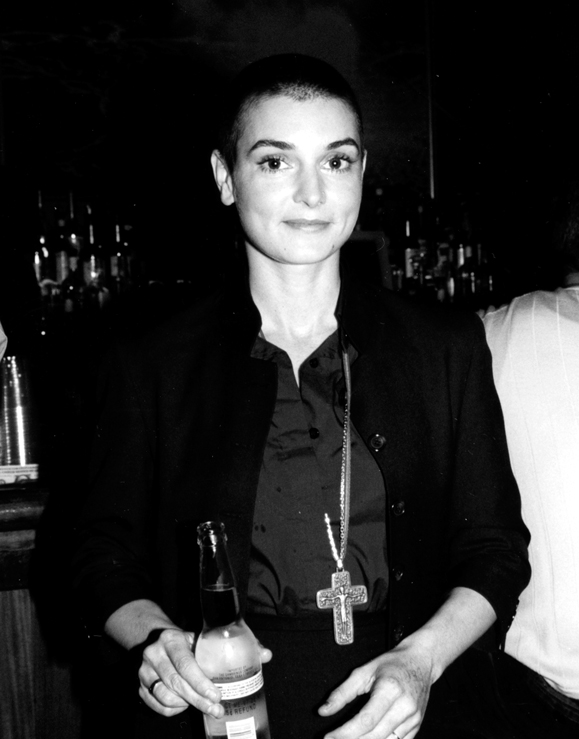

Before we examine their self-expressed doubts, let’s consider some of the names that grace the members’ board at Smith’s club. There’s Eugene O’Neill, Frank O’Hara, Bernardo O’Higgins. Conor Cruise O’Brien, Sean O’Casey, Sinéad O’Connor, Adam Duff O’Toole — and that’s just a few of the Os.

Who, you might ask, is Adam Duff O’Toole? It’s quite in order that we look at O’Toole’s credentials first as he had presumably been “down there” the longest, since 1327 when he was burned to death at Hogging (now College) Green in Dublin. Raphael Holinshed, from whom Shakespeare borrowed much historical material, wrote that O’Toole “denied obstinatelie the incarnation of our savior, the trinitie of persons in the unities of the Godhead and the resurrection of the flesh, as for the Holie Scripture, he said it was but a fable; the Virgin Mary he affirmed to be a woman of dissolute life…” So much for the late and unlamented Adam Duff O’Toole, burned at the stake.

Now, let’s look at some of the more recent dissenters. Sinéad O’Connor, the shaven headed pop star, enraged Catholics when she tore up a picture of Pope John Paul on the Saturday Night Live television show. Ah, but then in 1994 the situation changed, a priest helped her kick her marijuana habit, and she told The Irish Times that he had restored her faith in the Church. Surely this latest development should earn her exclusion from the book, but, perhaps, she’s only in there so we can see how close she came to joining the ranks of the doomed.

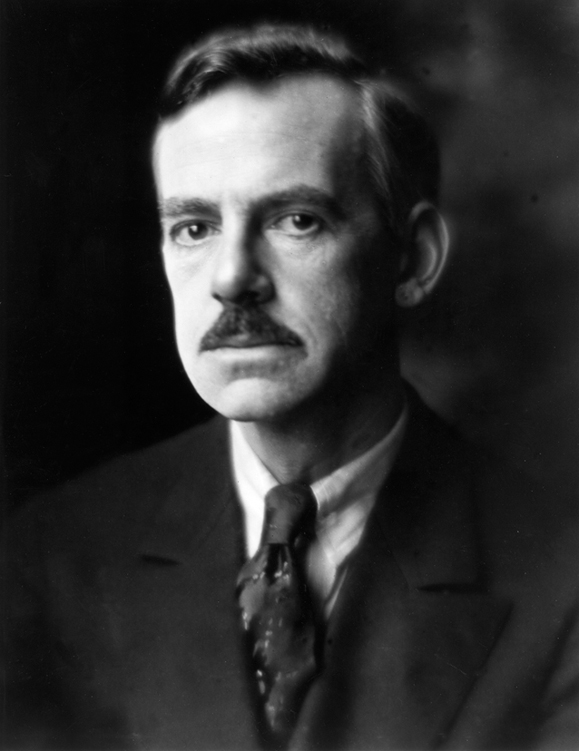

Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953), one of the foremost playwrights of the 20th century, was born in a hotel in New York City and attended a Catholic boarding school and Princeton University. In his play The Dynamo, in which he portrays the defects of an age which has witnessed the death of an old God and the failure of science and materialism, O’Neill clearly showed that he has rejected his Catholic faith. In 1936, O’Neill won the Nobel Prize in literature. According to his biographer, Louis Schaeffer, O’Neill told his wife, Carlotta, about two months before he died, “When I’m dying, don’t let a priest or a Protestant minister or Salvation Army captain near me. Let me die in dignity. Keep it simple and brief as possible. No fuss, no man of God here. If there is a God, I’ll see him and we’ll talk things over.” Close to the end O’Neill cried out, “I knew it! I knew it! Born in a hotel room, and goddamn it, dying in a hotel room.”

Séan O’Casey (1880-1964), the playwright best known for his plays Juno and the Paycock and The Plough and the Stars, was a Dublin-born Protestant. One of his plays provoked nationalist riots when it was performed at the Abbey Theatre in 1926. That was the year O’Casey moved permanently to England, remaining alienated from Ireland. According to Who’s Who in Hell, his various works have been grim, satirical and not always kind to the Irish people. According to British novelist George Orwell, O’Casey was “very stupid” and possibly a member of the Communist Party.

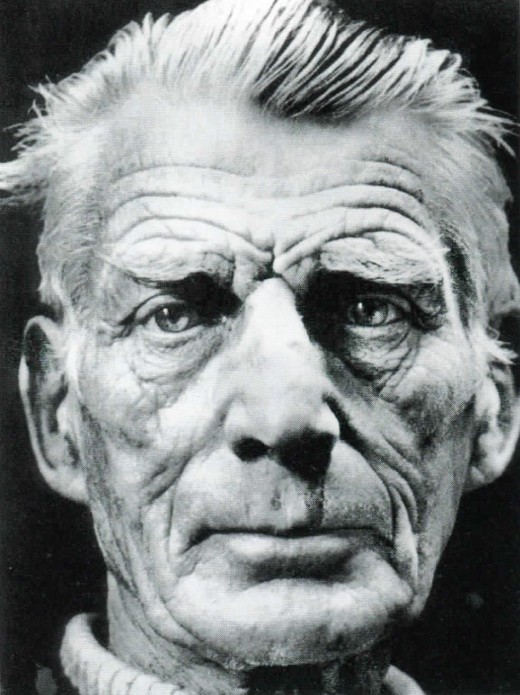

Two more of Ireland’s best known playwrights warrant inclusion in Who’s Who in Hell: Samuel Beckett and George Bernard Shaw.

Samuel Beckett (1906-1989), one of the greatest modern writers in English, was an unbeliever. He was born on Good Friday to affluent Protestant, Anglo-Irish Dubliners. His biographer, Lois Gordon, tells of Beckett’s friendship in the 20s with James Joyce. They liked each other, took long walks, smoked cigars, drank and enjoyed such repartee as “What do you think of the next life?” “I don’t think much of this one.” A friend said Beckett, who had begun to drink heavily and refused to hold a job, told him, “All I want to do is sit on my arse and fan and think of Dante.”

According to the Irish poet John Montague, Beckett included “God bless” in his greetings, an “uncanny salutation, a familiar Irish phrase made strange by his worldwide reputation for godlessness.” Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature after the success of Waiting for Godot. At the play’s end, the joke seems to be on the audience who assumes that Godot is God. But God is not there in any form, and this is one of Beckett’s purposes. “If Godot were God I would have called him that,” Beckett said in a little known statement.

Murphy, the eponymous character from Beckett’s first novel, made a special request in his fictional will. He asked, “With regard to the disposal of these my body, mind, and soul, I desire that they be burnt and placed in a paper bag and brought to the Abbey Theatre, Abbey Street, Dublin, and without pause in what the great and good Lord Chesterfield calls the necessary house, where the happiest hours have been spent, on the rights as one goes down into the pit, and I desire that the chain be pulled upon them, if possible during the performance of a piece, the whole to be executed without ceremony or show of grief.” Except that when his friend Cooper lugged the ashes but stopped off at a pub, a fight ensued and the bag of ashes scattered so that “…by closing time the body, mind, and soul of Murphy were freely distributed over the floor of the saloon; and before another dayspring greyened the earth had been swept away with the sand, the beer, the butts, the glass, the matches, the spits, the vomit.”

Unlike Murphy, Beckett’s own funeral and burial were traditional; bit of an anticlimax. Wonder what Beckett would have thought of that?

Beckett’s pal James Joyce, the famed Dublin-born novelist (1882-1941), was an outright freethinker. Joyce was educated at Jesuit schools. Disliking what he perceived as the narrowness and bigotry of Ireland (“that scullery maid of Christendom”) and Irish Catholicism, he spent most of the rest of his life on the Continent. The photographer Andres Serrano tells the story that Joyce, sitting for a painter who said he wanted to capture Joyce’s soul, was told, “Forget the soul. Just get the tie right.”

And George Bernard Shaw (1885-1950), let’s see why he’s right in the roasting with the others. Well, for a start, Shaw boldly proclaimed himself “…like Shelley, a socialist, and atheist, and a vegetarian.” Shaw had a 25-year exchange with a nun, Dame Laurentia McLachlan, during which both tried and failed to convert the other. She never forgave Shaw for his blasphemous picture of Jesus as “the conjurer” in his fable, The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God. Although he would never allow himself to be called a Christian, he can be classed as an unbeliever only in the sense that there was, as he said at the end of his life, no church in the world that would receive him, or any in which he would consent to be received. Shaw has written, “The fact that a believer is happier than a skeptic is no more to the point than the fact that a drunken man is happier than a sober one. The happiness of credulity is a cheap and dangerous quality of happiness, and by no means a necessity of life. Whether Socrates got as much out of life as John Wesley [the founder of Methodism] is an unanswerable question, but a nation of Socrateses would be much safer and happier than a nation of Wesleys.”

On the last day of his life, an hour before he died, and when visited by a friend, Ellen O’Casey, Shaw said wryly, “Well, it will be a new experience anyway.”

Then there’s James T. Farrell (1904-1979), author of the Studs Lonigan trilogy. Farrell wrote his own humanistic views in the Partisan Review of March 1951. “I was a Catholic until I was 21. I don’t have any violent feelings about it, and if people want to believe, it is their business.”

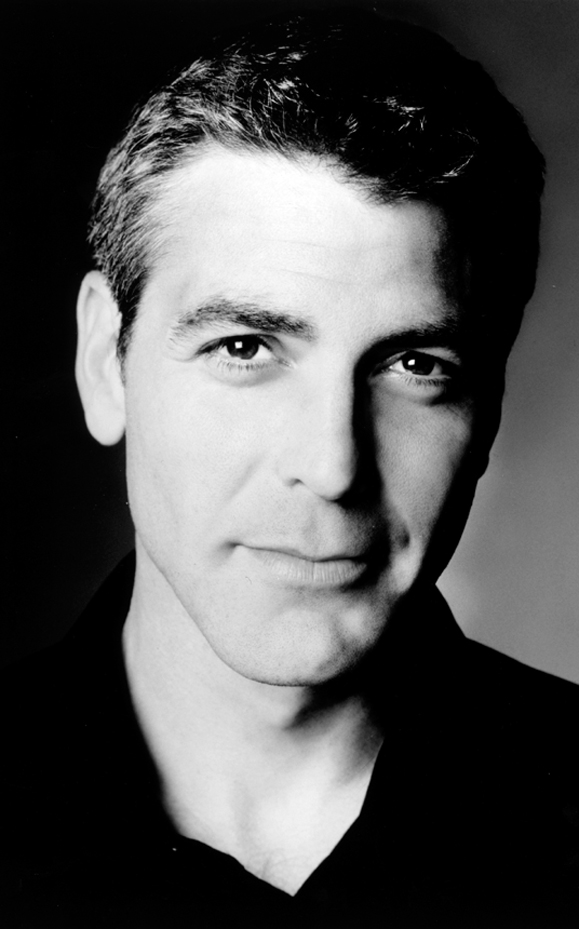

One hopes there’s a theatrical venue in Hades as there certainly will he no shortage of actors to cavort there. Just the ones with an Irish link would, alone, make splendid company. There’s George Clooney (b.1962) who was quoted in the Washington Post saying, “I don’t believe in Heaven and Hell. I don’t know if I believe in God. All I know is that as an individual, I won’t allow this life — the only thing I know to exist — to be wasted.”

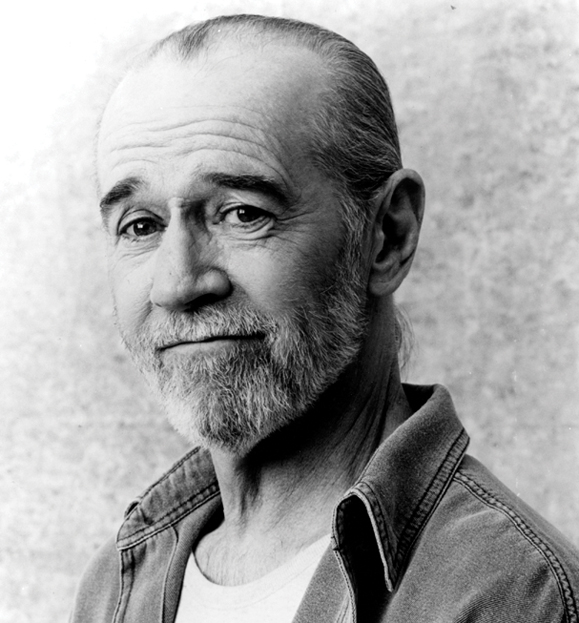

For comedy we might turn to George Carlin (b. 1937) who has appeared on numerous major television shows. The author of Sometimes a Little Brain Damage Can Help, he is often critical of the devoutly religious in his humor. “Religion is just a mind control,” he has stated. In Brain Droppings, another of his books, Carlin says, “I’ve begun worshipping the sun for a number of reasons. First of all, unlike some other gods I could mention, I can see the sun. It’s there for me every day. And the things it brings me are quite apparent all the time: heat, light, food, a lovely day. There’s no mystery, no one asks for money, I don’t have to dress up, and there’s no boring pageantry. And interestingly enough, I have found that prayers I offer to the sun and the prayers I formerly offered `God’ are all answered at about the same 50-percent rate.”

Carlin became the first recipient of the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s “The Emperor Has No Clothes Award.”

Sean Penn (b.1960), who received an Academy Award for Dead Man Walking and was married to Madonna, seems to have been granted what most men would consider a pair of most ambitious prayers. Nevertheless, he has gone on record as being an agnostic (George magazine, December 1998).

Ronald Reagan Jr. (b.1958) is the son of the 40th United States President. When Ronald was interviewing the murderer Charles Manson for a media program, Manson asked him if he believed in God. “No, I do not,” Reagan responded.

Actress Amanda Donohoe played the part of a pagan priestess who belonged to a snake-worshipping cult in Lair of the White Worm. In one scene she was asked to spit venom on a crucifix. Asked by Interview about the scene, Donohoe responded, “I am an atheist, so it actually was a joy. Spitting on Christ was a great deal of fun. I can’t embrace a male god who has persecuted female sexuality throughout the ages. And that persecution still goes on today all over the world.”

Author Mary McCarthy (1912-1989) described the Dickensian, nightmare of her youth in Memories of a Catholic Girlhood. Although McCarthy was convent-educated she stopped considering herself a Catholic once she left her paternal grandparents’ home.

Along with McCarthy in Who’s Who in Hell we also have Ellen McBride, Eamon McCann, Mildred McCallister, Betty McCollister, Wendy McElroy, Mary McEvoy, Todd McFarlane, Lewis A. McGee, Phyllis McGinley, Christopher McGowan and William McIlroy amongst a host of Irish.

Here’s a couple more “McDoubters”: Emmett McLoughlin who was a priest but left the priesthood and became a freethinker and wrote a book, Crime and Immorality in the Catholic Church (1962). And, how about S.J. McNeese who wrote An Appeal to Reason, or Sanity versus Faith (1924)?

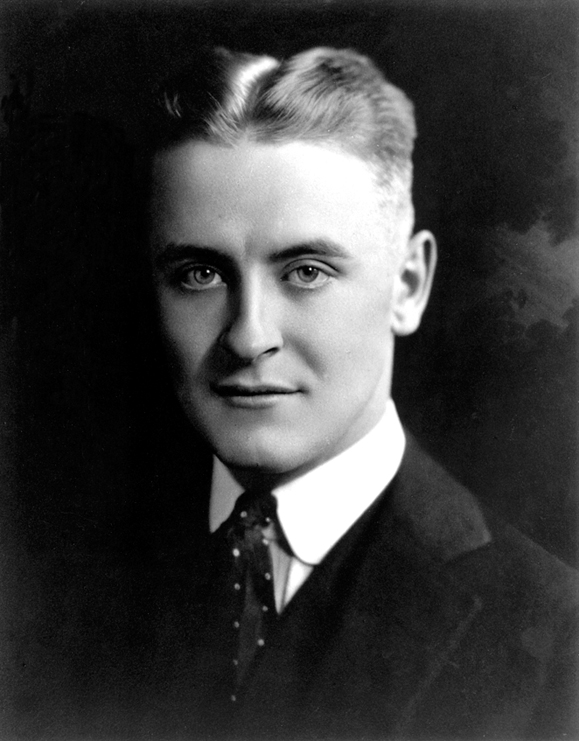

Another author, F. Scott Fitzgerald, was born Catholic and is labelled an unbeliever. He once wrote to daughter, Scotty, “Be sweet to your mother at Xmas…” That his faith is questionable is further supported by the fact that his handwritten will speaks of “the uncertainty of life and the certainty of death.” Fitzgerald got to check out that statement earlier than most — he died at the tender age of 44 in 1940.

Frank McCourt does not have his own separate listing in Who’s Who in Hell but his iconoclastic observations about the afterlife rate his inclusion under that heading. The author of Angela’s Ashes says, “My hereafter is here. I am where I am going, for I am mulch. It’s a great comfort to know that in my mulch-hood I may nourish a row of parsnips.”

The important thing to remember is that these people are not all atheists. Some are nondenominational theists. They all have this in common: they do not associate themselves with a church or organized religion and they do consider themselves freethinkers.

By the way, if you are interested in this sort of thing, there’s an Association of Irish Humanists, 5 Ailesbury Gardens, Ballsbridge, Dublin 4. There’s also a quarterly published in Cork calleid Church and State. Editor is P. Maloney, Box 159, Cork.

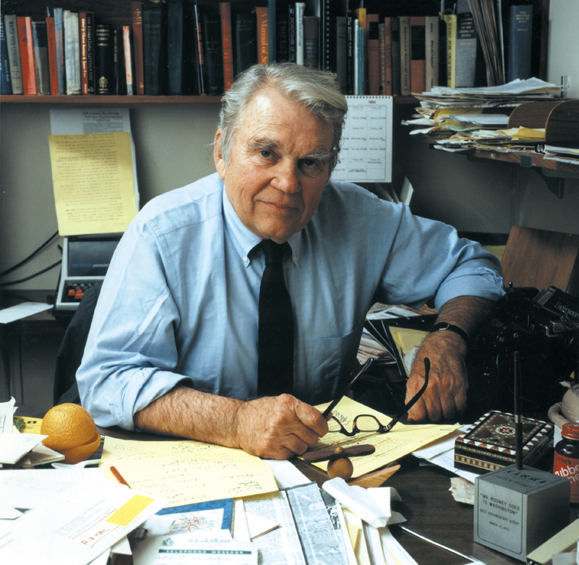

Like 60 Minutes we should close with a few words from Andy Rooney:

In a 1996 interview with Arthur Ungber in TV Quarterly Andy Rooney (b. 1919) was asked if people really knew him. He replied, “The only thing I hide from people, that I have never said so far as being blunt and honest goes, is that I am not a religious person. I’m not sure the American public would accept from me that fact. I don’t think that would please them or that it would attract a lot of people to me. And I take the position that it is a sort of personal matter, so I do not make an issue of it.”

The commentator from CBS’s 60 Minutes told Sam Donaldson on ABC’s Prime Time Live that he was “…critical of anyone who ever claims to know whether or not a god exists.”

Trust Rooney to be quite funny on the subject. “My wife’s from the Midwest. Very nice people there. Very wholesome. They use words like Cripes. `For Cripes sake!’ Who would that be — Jesus Cripes? Son of Gosh? Of the Church of the Holy Moly? I am not making fun of it — you think I want to burn in Heck?” Alas, he has already made it into Who’s Who in Hell.

These are just a few of the Irish in the pages of Warren Allen Smith’s Who’s Who in Hell, published by Barricade Books and available for a mere $125 at your local bookshop. Open it anywhere, it’s quite fascinating. How come George Washington and Abraham Lincoln are both included in its pages? Are you in it?

One thing is sure. With company like this, Hell won’t be a boring place to be. ♦

Leave a Reply