This year marks fiftieth anniversary of John Ford’s The Quiet Man, the favorite movie of many Irish Americans. The native Irish tend to see it with more ambivalence, yet the readers of the Irish Times in 1996 voted it the greatest Irish movie ever made.

The beguiling comedy-drama won Ford his fourth Academy Award as best director, as well as bringing Oscars to cinematographers Winton C. Hoch and Archie Stout for their spectacular Technicolor photography of rural Ireland. Based on a short story by Maurice Walsh that Ford had been wanting to film since the 1930s, The Quiet Man stars the director’s alter ego John Wayne as Sean Thornton, an Irish American boxer who returns to his birthplace in the fictional village of Inisfree (actually Cong in County Mayo) in an attempt to escape his violent life in America and find lasting peace. Maureen O’Hara, at her most ravishing, plays the fiery Mary Kate Danaher, who eventually becomes Sean’s wife despite the tyranny of her loutish brother, Red Will Danaher (Victor McLaglen).

Frank S. Nugent’s delightfully witty screenplay brightens the surface of Walsh’s rather grim story while adding greater intensity to the dramatic subtext of Sean’s guilty flight from his adopted land. A deeply personal film for the director, The Quiet Man reflects Ford’s own retreat from the modern world in the postwar years and represents a catharsis of sorts from his long obsession with combat both as a U.S. Navy officer and as a filmmaker.

After making the film in Mayo and in County Galway, where his people (the Feeneys) came from, Ford wrote his Irish relatives Michael and Sheila Killanin, “Galway is in my blood and the only place I have found peace…. [The filming] seemed like the finish of an epoch in my somewhat troubled life. Maybe it was a beginning.

“Hey, The Quiet Man looks pretty good. Everybody here is enthused and I even like it myself. It has a strange humorous quality and the mature romance comes off well…I think the Irish might even like it.”

Most Irish Americans find as many personal resonances as Ford did in this alluring and sometimes melancholy comedy of an exile’s return. The film’s romanticization of Ireland and its rustic western lands has given an immense boost to the tourist industries of Mayo and Galway for the past half-century.

From the time I first saw The Quiet Man in the 1960s, I was a typical Irish American male harboring a fantasy of going back to my own ancestral home, County Mayo, meeting a spirited Irishwoman like Maureen O’Hara, and living happily ever after in a little thatched cottage. In 1985, part of the fantasy came true when I met Ruth O’Hara, a recently arrived immigrant from Bray who had come to earn her Ph.D. in psychology at the University of Southern California. She accompanied me to Cong and the rains of the Feeney ancestral home in Spiddal to help research my biography Searching for John Ford (published in 2001 by St. Martin’s Press).

But there always remained one stubborn obstacle to the fulfillment of my Irish fantasies: Ruth thought The Quiet Man a deplorable film. I found this amusing, because it echoed in real life the theme of the film, Sean Thornton’s naive expectation that Ireland will live up to his romantic dreams. The comedy, and the drama come when he has to accommodate to the actual realities of life in rural Ireland.

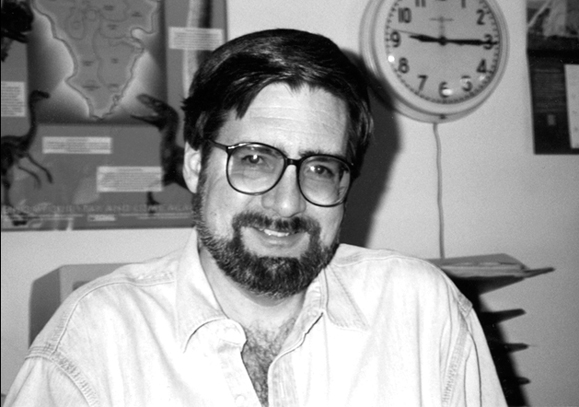

I dedicated my Ford biography to Ruth, “who urged me to write this book and gave me invaluable help and advice at every stage — even though she still doesn’t like The Quiet Man.” An assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, Ruth is a former professor of Irish studies at New College of California in San Francisco, where I now teach film and Irish studies. I recently sat down for tea with Ruth to compare our current views of The Quiet Man for Irish America.

ROH: My view of the film has certainly improved since 1985. There are aspects of it I do enjoy and scenes I think are magical and wonderfully acted. But I do think overall that The Quiet Man is a gross caricature of the Irish and indulges in some of the worst ethnic stereotypes of the Irish, particularly their supposed preoccupation with drinking and fighting. This is not conveyed in a subtle way in the movie so that it might capture the complexities of the Irish personality that perhaps have led to some of these stereotypes. I feel it’s done in a way that plays into the foolishly patronizing notion of the Irish so trenchantly satirized by G. K. Chesterton: “The Irishman of the English farce, with his brogue, his buoyancy, and his tender-hearted irresponsibility, is a man who ought to have been thoroughly pampered with praise and sympathy, if he had only existed to receive them.” The Quiet Man indulges in some of those stage-Irish stereotypes.

JM: When we went to Ireland to research the Ford biography, I made the comment, partly to tease you, that everyone I met seemed like a character out of The Quiet Man. I was taking a picture of somebody’s thatched cottage, and horse manure started flying over the wall — the guy was flinging it at me with a pitchfork. I could see that it was a crude American thing for me to be taking a picture of somebody’s home without asking. But you were embarrassed by the pitching of the horse manure because you said that’s the kind of behavior that reinforces these stereotypes. I was surprised about the extent to which a lot of people in Ireland behaved in ways that were similar to the film.

ROH: Well, I think the stereotypes in the film are appalling. There are aspects of the movie that ring very true. But the fact that Ford captured certain behaviors that people might encounter if they went to Ireland, or certain kinds of Characters, is different from insisting that the movie is stereotypical, because we’re talking about a measure of degree.

JM: When I met you, you said you were shocked by some of the American views toward the Irish.

ROH: Oh, absolutely. Before I left Ireland in the 1980s, I was living in an urban environment that was in many respects no different from the America to which I emigrated — the same TV shows, all modern conveniences, and so forth. I expected that people in America might have a nostalgic and romantic view of Ireland, but I did not expect the extent to which people would ask me, “Do they have proper clothes in Ireland, or do they still wear the old traditional clothes and shawls?” And, “Do they have roads and cars in Ireland?” Today, in the wake of the publicity for the Celtic Tiger and the new pride in the Irish economy, I wonder if I would hear that many questions speaking to the stereotype of Ireland as a backward, rural, peasant environment. John Ford is not the only individual guilty of perpetuating these stereotypes of the Irish. However, I think the success and popularity of The Quiet Man is complicit in continuing and reinforcing them.

JM: The Quiet Man has become the cinematic vision of Ireland for many people.

ROH: Until recently that was very much the case. However, in the last ten years or so we’ve had a significant thriving of the Irish movie industry, which has presented more modern views of Ireland such as My Left Foot, The Commitments, and A Man of No Importance. Although a common thread in all these is the Irish preoccupation with alcohol. And the view of Ireland as a primarily rural and backward country certainly persists. This is reflected not only in movies but even in Thomas Cahill’s introduction to his book How the Irish Saved Civilization, which states that Ireland is in many ways a third-world country. Yet Ireland has been for many years a first-world country with a far higher level of literacy and far lower infant mortality rates than places like the United States. To give Ford his due, when The Quiet Man was made, Ireland indeed was one of the poorer countries in Europe and was struggling with the conditions of poverty and the health issues just mentioned.

JM: That’s a lot to lay on the shoulders of one film made fifty years ago. And it’s about a man going back to Ireland hoping that he can recapture part of his childhood in a rural part of the country that is not as modern even as Dublin was in 1951, when the film was made. While Ford was filming in Cong, the ESB [Ireland’s Electricity Supply Board] was in the process of putting electricity into the town, so that was a somewhat technologically old-fashioned place. When you and I visited there thirty-five years later, the town hadn’t changed much — the buildings were all there and the landscape was much the same. Part of the appeal of The Quiet Man is the feeling that it’s like Brigadoon, it’s the Land That Time Forgot, it’s Shangri-La, it’s removed from things people don’t like about the modern world. There’s a quaintness to the film’s world that is appealing to people, but from the Irish point of view, you take that as more of an insult than a compliment.

ROH: The confusion comes from the fact that because the outward appearance of some place hasn’t changed, such as with Cong, people get the idea that it’s not sophisticated or educated or part of modern society. That’s just not correct. You’re quite right that rural electrification only came into Ireland in the fifties, but there were parts of the United States that were still being electrified only ten or fifteen years earlier. The bottom line is that everybody who lives in Cong would have their modern conveniences. However, there is an aspect of interpersonal relationships, camaraderie, attention to family, community life that still exists in rural areas, not just in Ireland but all over the world, that many feel we have lost in our modern urban society. And one of the things that people always comment on when they visit Ireland is how friendly people are, how warm they are, how engaged they are. The Quiet Man misses this tradition of Irish hospitality since the movie tends to cast it under the umbrella of drink.

What I am concerned about is if you’re portraying a culture as it is not. The Quiet Man gives an image of a group of people in this town as ignorant and unsophisticated. That is not, I believe, an accurate image.

JM: I would defend the film by saying that it’s partly about these mistaken attitudes toward Ireland that you’re talking about. Sean Thornton suffers from the romantic delusion that he can go back in time to a simpler, happier time that he associates with his Irish childhood and that he contrasts to his hellish life in America. When he verbalizes his feelings about Ireland to the local people, they scoff at him. He tells the Widow Tillane (Mildred Natwick), “Ever since I was a boy and my mother told me about it, Inisfree has been another word for heaven to me.” She replies tartly, “Inisfree is far from being heaven, Mr. Thornton.” The humor of the film comes from the constant confounding of his romantic ideas about everybody in the story — they don’t behave exactly the way he expects.

There is a level on which many of the characters are stereotypes, but most of them are also aware they’re stereotypes and they have fun with it. They’re ironic about their social roles, and so is Ford. The Barry Fitzgerald character, Michaeleen og Flynn, is one of my favorite characters in any film. Sure he’s a stereotype of the drunken funny little guy, the town drunk or the town character, leprechaun-ish. But Fitzgerald is a great actor and he does wonderful things with the nuances of the lines. There’s a sophistication in playing with the type that Ford does at his best. It’s not just indulging stereotypical behavior, but commenting on it at the same time. There’s a melancholy to the character too, so he has many dimensions. I think Ford transcends the clich?s and the stage-Irish stereotypes of the characters in most cases.

Not everybody in the film is falling down drunk. Michaeleen and Red Will are indeed portrayed as excessive drinkers. But Sean Thornton is not. And Mary Kate expresses disapproval of drunkenness more than once. The priest (Ward Bond) and the Protestant minister (Arthur Shields) are certainly not prodigious drinkers. It isn’t a society in which everybody is a lush. Even in the pub not everybody is drunk, a lot of people seem perfectly sober. Are you overstating your point because of a couple of characters in the film? Ford loves drunkenness as a comic motif.

ROH: Well, he loves drunkenness particularly among Irish people as a comic motif. In Ford movies such as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon [1949] or Fort Apache [1948], most of the characters who are preoccupied with alcohol are Irish. I find Victor McLaglen’s fight scene in the bar in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon ludicrous. Even if the characters in his films aren’t Irish, Ford indulges in that kind of brawling for its own sake. The Quiet Man could have tolerated some of that, but not as much as it has.

JM: Drink for Ford is a way of breaking down social barriers and making community harmony possible. Rather than seeing drink as a vice or a divisive thing, he usually sees it as a lubricant for getting people together. When Sean and Red Will are friendly because they’re both drinking together, Ford sees that as a positive thing.

ROH: They’re both drunk together. [Laughs]

JM: The wife doesn’t mind.

ROH: No, exactly. I also find Red Will Danaher a two-dimensional part, and that is compounded by the fact that Victor McLaglen is not a great choice for the role. One of the problems for Irish people dealing with the movie is that the lack of realism is further underscored by the fact that many of the characters have very erroneous accents. They have stage-Irish accents. Even Maureen O’Hara, who is a Dublin person and who is affecting a rural Irish accent and not successfully. Barry Fitzgerald and Arthur Shields are very good. But McLaglen is British and cannot really master the Irish brogue without it being extraordinarily stereotypical, a top-o’-the-mornin’ type of Irish accent.

JM: Des MacHale, who wrote The Complete Guide to “The Quiet Man,” takes exception to my view that the characters played by Sean McClory, Charles FitzSimons, Ward Bond, and Barry Fitzgerald are portrayed as members of an IRA cell. The dialogue refers to that quite clearly. McLaglen says, “So, the IRA’s in this too, eh?” And FitzSimons replies, “If it were, Red Will Danaher, not a scorched stone of your fine house would be standing.” Barry Fitzgerald adds, “A beautiful sentiment.” The priest is involved in this cell, they call it “The Committee.” But MacHale claims a priest would never be in the IRA.

ROH: Well, it’s not a topic on which I’m particularly knowledgeable, but I do know that some of our great patriots were priests. Way back in the time of the United Irish and the Rebellion of 1798, “Father Murphy from Old Kilcormac spurred up the rock with a warning cry,” so certainly there’s no question that priests have been involved in activities for Irish independence, not least by providing the Irish with the opportunity to obtain education and access to their religion when these fights were prohibited under British rule.

JM: Ford removed some of the political elements in the Maurice Walsh story, which deals directly with the Troubles. Ford decided to remove The Quiet Man from that situation. I think that’s fine, because the film is about something else and the political situation is a background to which it alludes. The grimness of Walsh’s story tends to work against the love story.

ROH: I think a significant theme of the movie is power and who has power. It’s about power in the ring, about power within the relationship of Sean and Mary Kate, power within the relationship of Mary Kate and her brother, the relationship of power with land and power with money. Another subtext in the film is a certain amount of chastising or concern over the “mercenary” nature of the Irish. Sean comes back with his romantic view of Ireland and he must deal with the hard, cold realities. There is a truth in that. The relationship among power, money, and land is very intricate in Ireland. And so there is obviously a subtext of oppression in The Quiet Man, but the real focus is on portraying this through interpersonal relationships.

JM: People who criticize The Quiet Man often object to the film’s sexual politics. Lord Killanin, Ford’s relative who in effect produced the film for him, pointed out, “It was not very popular here [in Ireland] at first and there were strong objections to the line from May Craig” — she’s the older lady who tells Mary Kate: “Sir, here’s a good stick to beat the lovely lady.” Ford finds this very amusing. The Irish people were offended, and many Americans think this is simply outrageous. I think the sequence is a big play-acting show that Mary Kate stages because she wants her husband to publicly desire her and bring her back. She thinks of him as running away from her brother and she wants him to go through the motions of acting like a caveman. It’s all tongue-in-cheek. But apparently that aspect of the film doesn’t bother you very much.

ROH: Actually, it doesn’t. I take that to be more reflective of Ford’s problems with women rather than reflecting any particular stereotyping of Irish people. It’s confined to a limited point in the movie, and certainly the comment of the lady is outrageous, but one comment in a movie does not ethnically stereotype the Irish.

JM: Ford is also satirizing things about Irish culture that he thinks are outrageous.

ROH: What’s interesting about that scene to me is that Mary Kate is very feisty and actually hits Sean several times. I’m not in any way condoning either character’s behavior, but I see that less as a smear of Irish people than as a reflection of some of Ford’s own preoccupations. In his 1963 movie about the South Sea islands, Donovan’s Reef, there’s an outrageous scene of John Wayne shaking Elizabeth Allen. That has to do with Ford’s personal inability to express emotion except through aggression.

However, The Quiet Man, by portraying such episodes as Mary Kate serving the men and showing her being at the mercy of her brother, is in many ways quite illustrative of how chauvinistic an environment it was in Ireland at that time.

JM: Red Will tyrannizes his sister, and she’s a frustrated, angry person, and while the film pokes fun at Mary Kate’s temper, her temper is justified because she’s treated as a lackey by her brother. It’s a very backward sexual politics that the town lives by.

ROH: Yes, and the film deals seriously with the issue of dowry and the belief that woman’s place is in the home. The Irish Constitution actually specified a strong preference for women to stay in the home.

There have always been conflicts within Irish culture about women — we were one of the first countries to give women the vote, and women have always been involved in Irish politics. But at the same time, until recently there was this view, tied to both the religion and the politics of the era in which we got independence, that women should stay in the home to look after the family, to be the caregivers.

The film is an illustration of the confinements, economically and every other way, that are placed upon her by the society in which she lives how she is under the control of her brother, how he wants her to stay in the house to look after him, which is not uncommon, and how she wants to keep something of her independence within her marriage, as represented by “her things.” However, at the same time I think Ford is also envious, at some level, of the situation between men and women in Ireland at the time. Part of the desire to go back to this romantic previous time represented by Ireland is also a desire to go back to traditional relationships “when men were men and women were women” and they knew their place.

JM: That’s a good point, because Ford’s films do have ambivalence about all kinds of things. And one of the constant themes in Ford is the nostalgia for the vanishing society or the vanished society, coupled with the recognition that it had to change. His attitude toward change is never simple, but in The Quiet Man that ambivalence perhaps is obscured by the visual beauty with which he idealizes this rustic paradise.

ROH: That ambivalence produces the most interesting aspects of the movie. It’s very interesting to get this complex mixture of, on the one hand, criticizing and recognizing and empathizing with the oppression that Mary Kate is encountering, much as Ireland itself was oppressed prior to independence. You can feel a great deal of sympathy in the movie for her. And at the same time there is a yearning for a situation in which the male is the dominant character dragging her across the field.

JM: You said you find some aspects of the film magical. What are you referring to?

ROH: I do think that through the cinematic aspects of the movie Ford beautifully captures the essence of the nostalgia that a returning emigrant feels for Ireland. The scene of Sean walking to the bridge the first night and returning to the cottage with Michaeleen is absolutely wonderful, the scenery is magnificent. It gives you a feeling of homesickness and a feeling for the genuine aesthetic beauty of Ireland.

JM: In visiting Galway, I was struck by how the light constantly changes in a truly spectacular way. Ford and his cinematographers Winton C. Hoch and Archie Stout capture the subtleties of lighting and color. That’s part of the allure of the film.

ROH: That’s absolutely true. And I must say that I do like the romantic aspect of the movie — it’s actually a very sexy movie when you get beyond the Irishness, the American-ness, so to speak, of both Mary Kate and Sean — you actually have some wonderful romantic scenes, such as the love scene in the graveyard. The scene in the cottage the first night is very charged and enjoyable. These scenes represent the best of Ford, and it’s unfortunate that they are interspersed with the broad gross humor and stereotypes that take away from the movie. ♦

Leave a Reply