They were busboys and bankers, grandmothers and newlyweds, firefighters, soldiers, tourists and priests. More than 2,500 of them died at their desks, or running down stairs, or clearing the way for others. Maybe a couple of dozen of them, on a plane over Pennsylvania, died swinging their fists. But on that cruel morning of September 11th, the morning of the most devastating terrorist assault ever on American soil, the only thing the 2,500 plus had in common was that they were dead.

Quickly, there were demographic trends. The Cantor Fitzgerald brokerage lost nearly 700 employees, a third of its total. Marsh &McLennan lost 295. Windows on the World restaurant, on top of 1 World Trade Center, lost 75 workers and 93 guests, talking business over bagels and coffee. And of course, the firefighters of the FDNY, while helping to evacuate some 25,000 people from the Trade Center, lost 343 of their “brothers.”

Americans were the target, and of course other nationals also perished. At press time the Irish government named more than a dozen of its natives among the dead in New York, Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania. Based on family names and individual stories, there are many hundreds of American dead with Irish heritage, including Americans who through parents or grandparents had become Irish citizens. The website www.IrishTribute.com, set up in reaction to the September 11 attacks, estimated that perhaps one-sixth of the dead were in some way `Irish.’

“September 11, 2001 may well go down as the bloodiest day in the history of the Irish people,” the website claims. “An estimated 1000 people who were of Irish descent or of Irish birth were lost in the violent events on that day.”

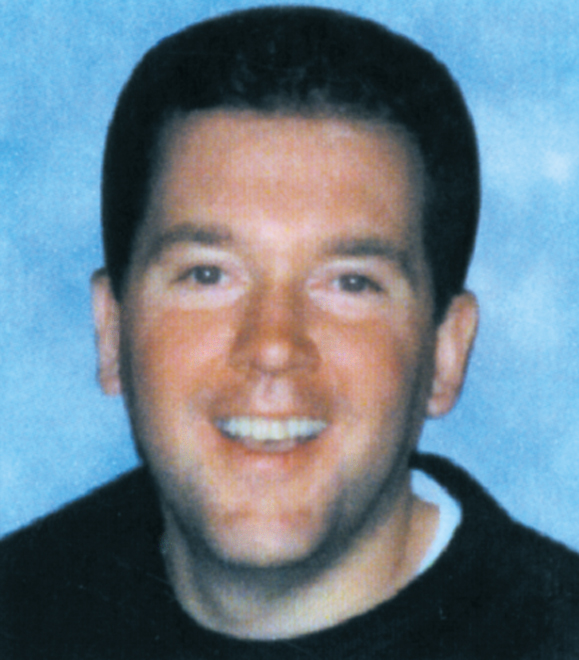

On that warm and sunny Tuesday morning, Tommy Foley was closing out the overnight shift at Rescue 3, in The Bronx. At age 32, Foley was already a ten-year veteran of the FDNY. It was the job he dreamt of since childhood, when he would visit the Harlem firehouse of a family friend, Firefighter Bob Conroy.

“Tommy Boy — that’s what I call him, ever since he’s a little kid,” Conroy said, still using the present tense. “I can still see Tommy Boy running around the firehouse in Harlem, running around and getting filthy dirty. It’s all he ever wanted to do.”

At 8:52 a.m., the call came in. Emergency in Lower Manhattan. An airplane or a helicopter or maybe even bombs, tearing through what New Yorkers call the Twin Towers. Instead of ending his shift, Tommy reached for his boots.

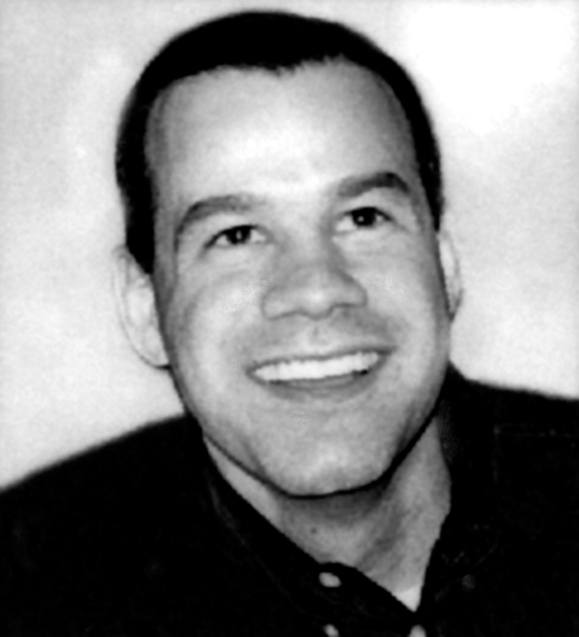

Across the city, the scene was repeated. The first airliner hit just as scores of firefighters were either coming off duty or arriving to work, thus maximizing the number rushing downtown. Mike Cawley wasn’t even on duty that day with his regular outfit — the `Elmhurst Eagles’ of Ladder 136 — but instinctively he raced to the Towers with another unit, Rescue 4. A 32-year-old bachelor like Foley, Cawley had been what firemen call a `buff ever since he was a kid, happily covering shifts for firefighters who had families, and racing toward smoke and flame even when he was off-duty. On a September 11 when he could have stayed away, Cawley of course could be no place else.

Meanwhile, AnnMarie McHugh had been at her desk inside Tower Two since early that morning. When not working for the EuroBrokers firm, the 35-year-old native of Tuam, County Galway, was busy planning her wedding, just a month away.

Over in Tower One, Mike Armstrong had even less time left before his `big day.’ The 34-year-old son of immigrants from County Longford, worked for the Cantor Fitzgerald brokerage firm alongside the Lynch brothers, Farrell (39) and Sean (36), whose uncle represents the Sligo-Leitrim constituency in the Irish Senate. Armstrong, a Manhattan native who was so outgoing and gregarious that his many friends long ago nicknamed him `Posse,’ was getting married to longtime girlfriend Cathy Nolan on October 6th.

At Logan Airport, the McCourts waited on standby. Ruth Clifford McCourt, a 44-year-old businesswoman who left her native County Cork as a teenager, was taking four-year-old Juliana on a vacation to Los Angeles. Mother and daughter found seats aboard United Airlines Flight 175.

Shortly after takeoff, of course, Flight 175 was yanked from its flight path by hijackers. As Ruth McCourt’s plane hurtled towards Lower Manhattan, it’s likely she never knew that her own brother, Ronnie, was attending a business meeting in the very same skyscraper where she and her daughter would meet their fiery end. Ronnie Clifford would escape the Trade Center without serious injury, only to learn later that one of the two planes that brought the Towers down contained his sister Ruth and niece Juliana.

Panic spread like brushfire across the country, and Navy Commander Robert Dolan was among those called to quell the flames. The 40-year-old husband, father and Little League coach often addressed his military colleagues with speeches that quoted everything from Shakespeare to Monty Python; he was equally adept commanding naval fleets that resemble floating steel cities. On the morning of September 11, Dolan was in his office on the first floor of the Pentagon’s D Ring, among a group hearing reports on that morning’s attacks in Lower Manhattan. At 9:43 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77 exploded through Dolan’s window.

“Bob Dolan was the best and brightest this country had to offer to the altar of freedom,” Lisa Dolan would later write about her husband of nearly 19 years. “We pray his rest is peaceful, although ours cannot be.”

The final plane to be hijacked that morning was United Airlines Flight 93. Because its passengers learned by cell phone that the morning’s previous hijackings were suicide runs, they obviously deduced there was nothing to lose from being brave. As Flight 93 rumbled through rural Pennsylvania, passenger Thomas Burnett spoke to his wife in California.

“I know we’re all going to die,” said Burnett, a 38-year-old father of three. “There’s three of us who are going to do something about it.”

By nature of the phone call to his wife, then, Burnett was among the lucky ones. With so few survivors pulled from the ruins, and hospitals across New York relatively empty because the dead so outnumbered the physically wounded, there were so many who never got the chance to say goodbye, never got the chance to say “I love you.”

Martin Coughlan also got to make that final phonecall. Shortly after 9 a.m., the 53-year-old carpenter from Cappawhite, County Tipperary, managed to call home from his jobsite on the 96th floor of Tower One. “There’s been a bomb in the building,” Coughlin told his wife, “but I’m OK, and tell the four girls I’ll be home for dinner.” Many days later, Coughlan’s remains were found.

One hundred and six stories from safety, Eamon McEneaney also called his wife. The 46-year-old vice-president at Cantor Fitzgerald was a heralded survivor of the 1993 World Trade Center attack, when he calmly covered the mouths of co-workers with wet towels and led human chains down the stairs. On September 11, the father of four left a message at his wife’s office: a plane had hit the building, he was on the way out, and he loved her. McEneaney never made it out.

Unlike McEneaney, John O’Neill managed to escape. The 50-year-old former FBI man had been named the Trade Center’s Director of Security just two weeks before. He made it from the 34th floor to the street, from where he called his son to report that he was safe. Then O’Neill reentered one of the Towers, joining the human sacrifice that was under way in the name of evacuating others.

In Spring Lake, New Jersey, the McAlarys leapt for joy when their son and brother Bryan phoned to say he had escaped unharmed from his Trade Center office. They were soon horrified to learn that Bryan’s older brother James — a 42-year-old broker — was in the Trade Center that day for a sales meeting. “Jimmy Mac,” as he was known to all, never came home.

The McAlarys were but one of many sets of brothers at the scene that day. At the base of the Towers, Michael Moran of Rescue 3 spoke by cell phone with his big brother John, a 43-year-old Battalion Chief — they were brothers by blood and `brothers’ by profession, among the fraternity of the FDNY. “I told him to be careful,” the younger Moran would recall weeks later, at a memorial service for John. “I didn’t see him there that day, but now I see him all the time.”

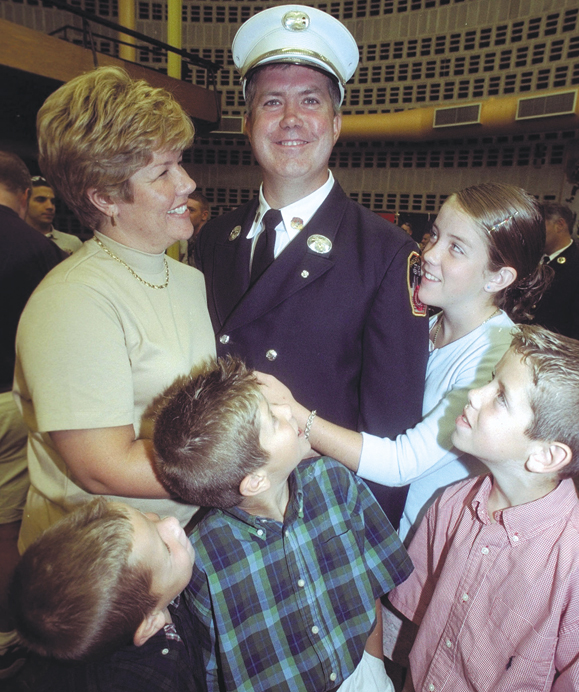

Maureen Haskell, a Fire Department widow, sent three of her four boys — Kenny, Timmy and Tommy — to the FDNY. Timmy, 34, was on the 60th floor of Tower One when the floor dropped beneath him. Nearly two weeks after the attacks, Maureen listened as Kenny gave a eulogy, Timmy’s remains lay in a casket, and Tommy was still in Lower Manhattan, one of thousands lost in the mountain of steel and smoke.

“We need to pray for Tommy’s safe return…I’m sure he’s fine,” Kenny told those who gathered to bury Timmy, in Seaford, Long Island. “Tommy’s probably sitting comfortably down there in a large void, wondering — what’s taking us so long?”

Kenny Haskell vowed to retrieve his brother, as did Danny Foley, who seven years ago had followed his above-mentioned elder brother Tommy into the FDNY. Danny worked around the clock with rescue crews searching for the brother that he idolized, and nearly two weeks after the attack he addressed mourners at St. Anthony’s in Nanuet, New York: “It took ten days, but a promise I made to my family was kept, when I brought Tommy home.”

Danny recalled the nights spent talking across bunk beds to his older brother, discussing what he called their common interests: football, fishing, becoming a firefighter, and girls. In later years, he recalled joking about his big brother’s pin-up pose in a firefighter’s calendar, a charity fundraiser that led to modeling jobs and appearances among `eligible bachelors’ in People and also the `Top 100 Irish Americans’ list published by this magazine. “I knew someday I wanted to be just like my big brother,” Danny recalled. “He’s always been a hero to me, and now he’s a hero to people around the world.”

Bob Conroy, the family friend who earlier recalled the young Tommy Foley running around a Harlem firehouse, and would later become the Foley brothers’ FDNY mentor, echoed the sentiments of so many families and friends when he said, “I only wish I could see him one more time — just one more time to tell him how much I love him.”

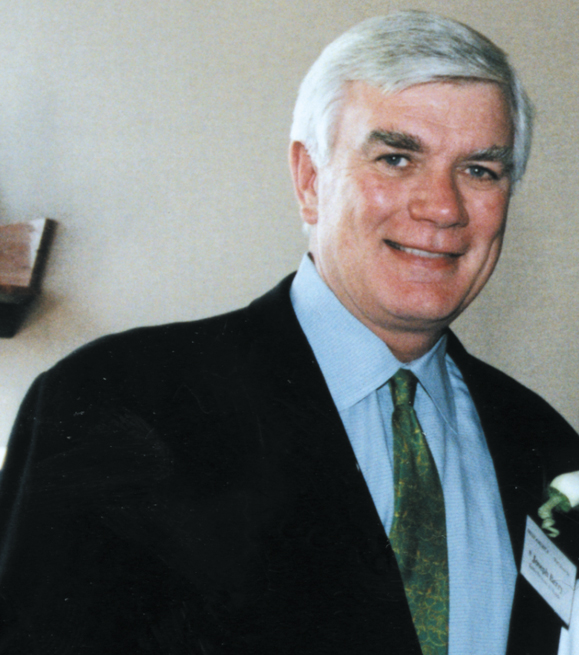

Foley was not the only September 11 victim to have previously appeared in the pages of Irish America magazine. Of the more than 70 employees lost from Keefe, Bruyette &Woods, two were former honorees among the Irish American `Wall Street 50′ — Chairman &CEO Joe Berry and Executive Vice-President Joseph Lenihan. Another victim from the same firm, Chris Duffy, was the son of `Wall Street 50′ honoree John Duffy. Berry, Lenihan and the two Duffys were among those who attended Irish America’s Wall Street 50 reception on July 11, an event that was held annually at Windows on the World restaurant. At the top of Tower One, the breathtaking view from Windows on the World was the ideal setting to toast the many achievements of the Irish and their descendants in the U.S. As of September 11, that skyline view has been lost forever, but of course the accomplishments of people like Berry, Lenihan and the Duffys remain.

The accomplishments of others were never recorded and may never be known. The unborn second child of Damien Meehan will never know daddy first-hand, how he grew up playing Gaelic Football with five brothers in Good Shepherd Parish, Upper Manhattan. How among the Donegal Meehans of Upper Manhattan, Damien was the first to enter a `safe’ profession — becoming a financial foot-soldier on Wall Street, instead of a fireman or a cop. How on September 11, 2001, the 33-year-old reported to his desk at Carr Futures in Tower One and then disappeared; vanished forever.

In Northern Ireland, they will never know of the woodwork yet to be crafted by 21-year-old Brian Monaghan, who had emigrated to the Meehans’ neighborhood in Upper Manhattan. Joint ceremonies at Good Shepherd Church, Inwood, and St. Patrick’s Church, Belfast, recalled the hurdles young Monaghan and his family had overcome to date, and all the promise the young carpenter had left to give.

In Dublin, they memorialized Richard Fitzsimons, who traveled to the Irish capital from Lynbrook, Long Island, just weeks before, to dance at his niece’s wedding. In New Jersey, they play `The Minstrel Boy’ just a little bit quieter now in memory of three fallen `Irishmen’ of sorts from the Port Authority Pipe Band — Steve Huczko, Liam Callahan and Richard Rodriguez. In the Bronx, a widow cries because her husband and the father of her two baby girls, 31-year-old cafeteria worker Israel Pabon, left for work at dawn after a minor domestic squabble the night before: “We never got the chance to talk…”

The sacrifice is staggering, the waste of life too much to bear. In Woodside, Queens, and Breezy Point, Brooklyn, families of cops, firemen and brokers with Irish names are forever wounded. There are Brooklynites like Captain Timmy Stackpole, who just weeks before had laughed while being named `Irishman of the Year’ at the Coney Island Irish Fest, and there are Bronxites like Ann McGovern, who bragged of a recent hole-in-one on the golf course. A vice-president at the Aon Corporation of Tower Two who had recently become a grandma for the fifth time, McGovern had many accomplishments and perhaps even more loved ones who gathered to mourn at St. Brigid’s of Westbury, Long Island. From the altar, Ann’s husband summed up perhaps the most important lesson learned by untold thousands since the attacks of September 11.

“Don’t be afraid to tell people you love them, when it could be the last words spoken,” said Larry McGovern, near a poster-sized photo of Ann with her youngest grandchild, Liam. Cocking his head to the church roof, McGovern said in a cracked voice: “I love you.” ♦

Leave a Reply