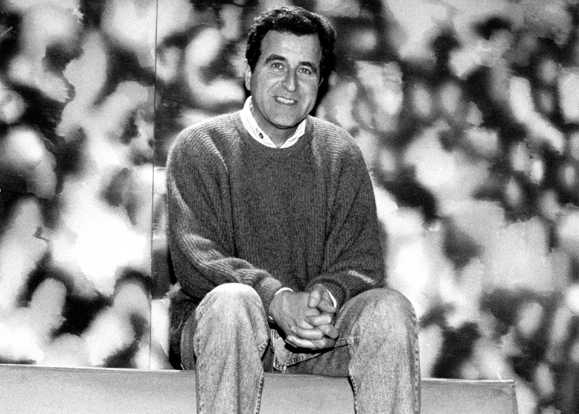

Nicolas Kent, the man behind the Tricycle, the uniquely innovative theater in Kilburn and launching-pad for many of Ireland’s most successful plays, is interviewed by Marilyn Cole Lownes.

℘℘℘

It’s 10 a.m. on London’s busy Kilburn High Road and the Tricycle Theatre, emblazoned with flashing lights, is already open for business and ready for action.

Sandwiched between the austere facade of “The Ancient Order of Foresters” and a music shop, this tiny gem of a theater literally sparkles in a funky carnival way that belies its serious posture in the British theater scene today.

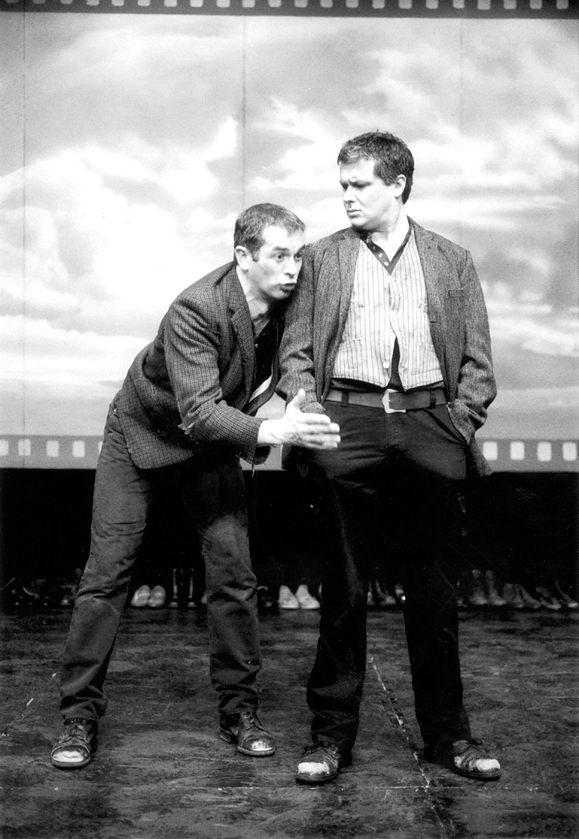

It is famous for its award-winning, often political, Irish and black plays such as Stones in His Pockets — recently a hit on Broadway and London’s West End — and The Colour of Justice: The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry about the trial of those accused of murdering a defenseless black youth.

The Tricycle Theatre reflects its local Irish and black audiences but, more significantly, Nicolas Kent, its brilliant artistic director.

Passionate and progressive, the 56-year-old Cambridge-educated Kent is a man with a mission. His relentless energy, dogged determination and vibrant vision have made the Tricycle the uniquely innovative and successful place it is today.

Sipping cappuccino in the Tricycle’s café-bar, Nick describes his terrain. “This area is referred to as `County Kilburn’ because Paddington station was the first place people arrived at on the Cork-to-Fishguard boat train.” Kent continues, “If they went south they’d end up in Belgravia where they couldn’t afford the housing so they came up here instead. It’s said that they arrived here because one could carry a suitcase in one hand only so far and you’d stop here when you had worn out both hands.”

Nick smiles warmly. “And it’s the only high road in London where the liquor licensing laws are interpreted rather broadly and where you can buy at least 50 different Irish newspapers.”

Looking around at the trendy bar, attractive art gallery and the theater itself with its unusual steel scaffolding balcony structure, one sees that The Tricycle is an eclectic mix that’s both charming and functional. Nick’s artistic flair and entrepreneurial eye seem to come from his parents. “My father was a German Jew who came here before the last war and married my mother. He was gregarious and a successful business man while my mum was English, more restrained. She bought art for Selfridges department store.”

Nick continues, “I spent three wonderful years reading English at Cambridge where I was very much influenced by one of my tutors, Thomas Henn, who was an expert on Yeats and Synge. In fact, he wrote the definitive book on W.B. Yeats, The Lonely Tower. I joined the Amateur Dramatics Club where I put on Synge’s Playboy of the Western World which was not only my father’s favorite play but one that has haunted my career. It not only is a wonderful narrative but contains a marvelous truism, I think. It says that you have to metaphorically kill off your father or the parent inside yourself to achieve manhood. It’s a model of good drama that reaches a universal audience.”

After leaving Cambridge in 1967 Kent went on to work as stage manager and productions manager at various theaters from Liverpool Playhouse to the famous Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh. “I worked with Michael Rudman and with Richard Eyre who was running The Lyceum in Edinburgh at the time.” Nick Kent mentions other leading producers and directors who were working in the provinces at that time. Bill Bryden and Max Stafford Clark were doing interesting new plays and had a definite influence on him. “It was very exciting. That’s when I really got the bug to do new plays,” Nick continues. “I went on to do plays for the BBC television before doing plays on tour for the British Council.

“We took Macbeth to Japan and Korea and Zambia and Tanzania. I joined the British theater and saw the world,” he quips.

The big turning point in Kent’s career came when he worked as a director for the Oxford Playhouse in 1977. “I commissioned Mustapha Matura, the Trinidadian-born playwright, to write a version of Synge’s play The Playboy of the Western World,” recalls Nick. “It was called Playboy of the West Indies and it was a tremendous success from the start. It then transferred to the Tricycle and became that theater’s first sell-out! Then we did it for BBC TV and since then it has been performed at the Lincoln Center in New York and I directed it for the Chicago Theater Festival.”

It was in 1984 that Nick was invited to apply for the position of Artistic Director of the Tricycle. “It was really run down. My predecessor, Ken Chubb, a Canadian, who had originally founded The Tricycle company above a pub in King’s Cross, London, discovered this space in Kilburn which had been a Masonic Hall owned by a lodge called The Foresters.”

Kent explains, “It had fallen into disuse and the local authority in Brent used it as a housing office during the Second World War. Chubb had converted it, basing the design on a structure that he had seen in the Georgian theater in Richmond, Yorkshire, Britain’s second oldest theater.

“He used steel scaffolding rather than the wood of the original 1788 version. The Cottesloe at the Royal National Theatre and Tina Packer’s Shakespeare Theater in Massachusetts have also adopted that same layout,” informs Nick.

“Unfortunately, after four years on the new Kilburn site, the Tricycle had run out of steam and, when I took over, they were giving away more tickets than they were selling. The local council was threatening to take away the financial grant that supported the venue.

“When asked what I would do if the council did take away the grant, I replied that I’d fight to keep the place open, although I wasn’t quite sure how I would do that,” he admits.

“I also promised that unless I doubled the box office figures by the end of the year, I’d resign. The figure is engraved in my mind. We went from 54,000 pounds to 115,000,” Nick happily recalls. He attributes his success to several factors, crediting his predecessor with some of them.

“We tried to take more account of our audience’s interests. This is the most multiracial borough in all of Europe, so I tried to reflect this community’s complexion as much as possible — to stage Irish plays, black plays, Jewish and Asian works, too.”

Kent continues, “After three years I felt confident that things were working out, and, then, disaster struck!” Nick cautions, “Never build a theater next door to a timber yard. The yard caught fire and it spread to us and the whole place burned down in 1987. We lost it completely and because of the economizing of the local council they had not updated the insurance so we were only covered for about a quarter of its value. We had to rebuild the Tricycle.

“We’d just put on James Baldwin’s The Amen Corner which we’d transferred to the West End, London’s Broadway, and the play that replaced it was, ironically, entitled Burning Point,” Nick adds with a wry smile.

“It was the biggest fire in North London for years and we had to spend the next two years raising money to rebuild the Tricycle. At the same time we did do productions in other theaters to keep our team together and our name before the public.”

Undaunted, Kent raised over a million pounds to rebuild the venue, even adding to the space. “We built the new James Baldwin studio which gave us a separate site for community activities and children’s theatrical workshops.

“We reopened with an August Wilson play brought over from the States. We also did a Brian Behan play, he is Brendan’s brother. We had already done Brendan’s The Hostage before the fire. We’ve formed alliances with a number of Irish companies, like Druid, who came over with At the Black Pig’s Dyke, a wonderful political tragedy which Gary Hines directed. Then we did A Love Song for Ulster, a six-hour trilogy of plays about Northern Ireland. We did Seamus Heaney’s A Cure at Troy, the Nobel Prize winner’s only play, and it was a great success.”

Analyzing the undisputed critical and popular success of so many of his Irish plays, Kent says, “The magic of the Irish is great storytelling. When we did J.B. Keane’s Sive, the Irish Ambassador in England came to see it and afterwards he made a speech about the impact of Irish theater on the English stage. He told us some things that I didn’t even know, like that between the years of 1780 and 1850 2,800 plays were performed in London and at least 1,800, that’s about two-thirds of them, were Irish.

“So it’s completely wrong to say that this present invasion of Irish drama is a new thing in Britain. Sheridan was Irish, Goldsmith was Irish, as was Wilde.” He explains, “We may have colonized Ireland but they have been the ones who colonized our stage.

“Recently there has been a renaissance of Irish play-writing stemming partly from the Troubles.” Nick theorizes, “Also, in the late ’80’s the Tricycle was a theater on the front lines because of the work we were doing. It was political to some extent because I always wanted to reflect our local audience’s viewpoints and concerns, and at that time we were right in the middle of two wars that very much concerned them.”

Kent explains, “There were two wars of independence going on. The first was in Ireland for the Irish Nationalists, not that we were taking sides in that battle. The other war was against apartheid in South Africa. We brought over work from the Market Theatre in Johannesburg. We wanted both our black audiences and our Irish audiences to be able to see plays about their respective political struggles.

“You’ve got to see our Saturday matinee audiences. They’re quite elderly now, and I always say that it’s made up of people who were around the Post Office in Dublin in 1916, elderly Marxist Jews who just love theater, and rather senior members of the ANC (African National Congress) who were stranded here during apartheid and decided to stay when it collapsed.”

Nick grins. “We love them because, while many other older theatergoers might go to sleep, our oldsters have brought lively inquiring, challenging minds.

“With the peace process in Ireland and the collapse of apartheid we’ve been left with a bit of a vacuum,” declares Kent. “We had done Love Song for Ulster before the peace process started, which was good because it actually was a play that looked at the division of Ireland from a 1923, not from a 1916, perspective. This was a good thing because it was a Belfast perspective — a predictive play, projecting forward to today.

“Now, because of the changes in Ireland and South Africa there are interesting new dramas coming out of both societies adjusting to the peace process. We’re hoping to do the new Gary Mitchell play called As the Beast Sleeps, which is about the UDF, the extreme loyalists and how they’re coming to terms with the ceasefire. These are people who were robbing banks and setting up illegal drinking clubs to raise money for the armed struggle. They don’t need to do that now, so the play is concerned with how they restrain their members and keep them from stepping out of line and discourage them from continuing to rob banks. It’s a very violent play about the clash of ideologies — gang against gang.

“Also, with Ireland’s booming economy, it’s beginning to look at itself socially now, whereas, in the past, it tended to look backwards in its drama. Look backwards to the relevance of the struggle of 1916. Now, it’s a society that suddenly has to cope with black immigration, an agricultural society having to deal with urbanization. Ireland is now a part of Europe and it has to face integration. All these new factors are fascinating to Irish playwrights and audiences.

“And it’s the same with South Africa. Will the Rainbow Coalition and the Truth Reconciliation Commission work? Will they be able to avoid retributive justice and stick to restorative justice? You are watching new societies in action. What’s happening now is that in both South Africa and Ireland, people are having to learn to work within a peace process and to bury old enmities, to try and find new ways to go forward together.

“I think the peace process will be advanced by the EEC, which will diminish the extreme importance placed on nationalism. Although we’ll definitely have McDonalds everywhere, people will still assert their own unique culture and language, too. That’s why we’re getting devolution in Scotland and Wales. Gradually power is going to the grass roots level.

“There may be a unified super-state of Europe but people will still want to assert their own special cultural identity. One way that this happens is through the theater and its way of storytelling.”

Nick emphasizes the relevance of this to the Tricycle, “And that’s what the Irish are profoundly good at, what they share with the Caribbean and African communities. That’s why The Playboy of the West Indies worked so wonderfully well as a translation from the original Irish setting, because it’s classic myth-making, a cornerstone of both cultures. They both love language. In a way, both are working in a second language that has been imposed on them — English. Perhaps it is like when someone gives you a gift, you feel the need to make it your very own, to rejoice in it. Then again, when the gift is forced on you, you may feel the need to corrupt and pervert it, turn it back on itself and use it even better than the people who originally owned it.”

Nick concludes, “I think that both cultures have actually enriched the English language.

“We’ve had a long relationship with Marie Jones,” one of the Tricycle’s favorite playwrights. “We did her adaptation of Gogol’s The Government Inspector which she set in Ireland, and her play A Night in November with Dan Gordon, which was also a success in New York. Then we did Marie’s Stones in His Pockets which she started in The Lyric in Belfast. After we launched Stones in London it transferred to the West End and also went to Broadway. It won the Olivier Award in London and a Tony Award in New York.

“The play I’m most proud of is The Colour of Justice which was about the Stephen Lawrence inquiry,” says Nick. “It changed people’s conceptions. It was about the murder of Lawrence, a black teenager, and the inquiry which followed after the five white suspects had either been acquitted or not even charged by the police at the trial. The paperback book of the text got onto the best-seller list, the first time a play has ever done that.

“It’s close to my heart because it’s about the two things I feel most strongly about — social justice and racism,” Kent states. “I suppose that’s why I’m drawn to the Irish, because my father escaped persecution by the Nazis by coming to this country. He was an asylum seeker at that time, so I can’t bear to think that there should be any restrictions on asylum seekers today. What I abhor most is racism,” Nick is adamant.

“Everything we do here at the Tricycle is meant to celebrate the cultural diversity of Britain. People in the States forget that while they’ve had over 250 years to live as a multi-cultural society, we’ve only had about 50 years to live with that — it’s difficult, of course, but we’re getting there.

“I’ve always found that there’s a very good relationship between the Irish and the black communities in this area. The Irish come to see the black plays and vice versa. They are so fast they tend to know the joke, to catch themselves on and to come for good craic,” he laughs. Industrious and innovative as ever, Nick declares, “We’ve been busy adding a children’s painting studio, a rehearsal room and a cinema. When we opened the cinema three years ago, with film star Emma Thompson as our patron, we held an Irish film festival in conjunction with Ireland’s Ballygowan Festival, screening 50 Irish films in one week; that’s become an annual event and it is now sponsored by Ballygowan.”

Nick reveals, “My goals for the immediate future are to put the cinema in profit and to commission nine writers to give us some more good new plays.

“It’s lovely to be cherished as an individual and, in a way, what I try to do with this theater is to cherish certain distinct cultures, to make people proud of themselves. Whether it’s a black or an Irish play, people can feel that they are showing off the best of their cultural creativity.

“That’s what I like to do,” concludes Nicolas Kent, adding, “And it’s fun!” ♦

Leave a Reply