Christmas is one of those words that immediately brings thoughts to mind. First, and foremost in these troubled times, is the hope for peace on earth. Hard on the heels of our heartfelt sentiments come the tumbling images of gifts and feasting.

Deluged by jolly Santa Clauses, decorated evergreen trees, and twinkling light displays during the holiday season, it’s easy to forget that the roots of Christmas lie in pagan mid-winter solstice celebrations. The sun’s light and heat were feeble, and people beseeched their deities to protect them during the hard, lean winter.

We can thank the Romans for initiating the tradition of giving gifts. They called the time Saturnalia in honor of Saturn, king of all the Roman gods. He taught the people of Earth how to fashion gold into coins resembling the sun in the sky, and the Romans exchanged gifts of coins in his honor.

When Christianity superseded the old ways, the Church sought to erase pagan celebrations by naming December 25th the Feast of the Nativity. It made sense. Winter solstice celebrations honored the sun gods. The Christ Child was the Son of God and the Light of Redemption. For Him, the lion would lie down with the lamb, and in His name Christmas became a symbol for peace in the land.

Celebrating the darkest days of winter with lavish meals is a custom that’s as old as civilization itself. Winter was once a fearful time. Many months would pass before crops could again be harvested. Without a cache of food, many people would die and only the strongest livestock would survive. Common sense dictated that weak animals should be slaughtered. After sacrificing them to honor the sun god, most of the meat was salted and dried for later use, but there was plenty for a feast.

Since the Celts measured their wealth in cattle, beef was the central element of the solstice feast. During the Middle Ages, returning Crusaders brought exotic spices from the East and spiced beef became a fixture of the Christmas meal. When Cortez returned from his New World expeditions bearing samples of the foods he had found in the Americas, turkey soon became the favorite feast bird in Europe. Today it shares the Irish holiday spotlight with beef and goose.

When did goose enter the picture? It’s been there since the beginning. Archaeological remains show that Slavic, Scandinavian, and Celtic people domesticated the goose concurrent with the Egyptians — approximately 1600 B.C. as shown by carved stella portraying the magistrate Schetep-Ab sitting at a table laden with assorted poultry. It was the Celts, however, who began the tradition of serving goose at winter solstice celebrations.

Eliminate the ease of ever-present everything at modern supermarkets, and goose makes solar feasting sense. Geese are migratory, coming and going with the seasons. When the wild birds paused on their long flight to feed, canny Celts found them easy to trap, and domesticated geese became part of a household’s livestock.

Goose eggs, which were bigger and richer than those of any other fowl, were prized as special treats. A story attesting to this occurs in The Banquet of Dun na nGedh and the Battle of Magh Rath which dates from the 7th century. King Donall needed some goose eggs to serve at a feast in his new fort on the banks of the River Boyne, but the only ones his servants could find belonged to a saintly hermit who lived exclusively on goose eggs and water-cress.

Ignoring the pious man’s need for his daily meal, the servants stole the eggs, but when they were served to the guests on silver platters, the plates turned to wood and the eggs to common hen’s eggs. This so insulted some of the Ulster guests that the feast turned into a fierce battle.

Eventually, gaggles of geese ranged freely over the countryside since even a poor family could afford to raise several geese which were less trouble to maintain than cattle. An Irish adage states, “Everything about a goose is used except the honk.”

As today, goose down and feathers filled pillows, mattresses and comforters, but that was just for starters. Hollow feather quills shaved into fine points made fine writing implements; like pencils they could be sharpened again and again until they became too small to grasp. A quill’s sturdy hollow structure made it a good float that alerted an angler as soon as a fish began nibbling on the line. Housekeepers used feather clusters as dusting tools, and cooks used the wings to sweep flour from their griddles. Goose fat was prized for the flavor it imparted to fried potatoes, but its uses ranged from chest rubs for curing colds and salves for easing the ache of sore muscles, to polishes for rubbing on iron pots and stoves to `bring up the shine.’

Best of all, spring-born goslings reached maturity just as the weather turned chill and the specter of winter loomed on the horizon. The timing made roast goose perfect fare for three celebrations: Michaelmas (September 29), St. Martin’s Eve (November 11), and Christmas.

All summer, geese had ranged in fields and meadows feeding on tender green grass and grain shoots. Once the fall harvest ended, they foraged amid crop stubble. Roasted `green’ geese were exceptionally tender and considered a great delicacy, whereas the season’s later `stubble’ geese had a more robust texture and taste. Frequently `green’ geese were kept caged for two weeks prior to slaughter and fed only milk and potatoes, which ensured that the meat would be pale, tender and even more delicately flavored.

Michaelmas, the day set aside to honor St. Michael the Archangel who defends the innocent against evil, marked the beginning of goose season, and was known as Fomhar na nGean — the Goose Harvest.

It was also the day for tenants to pay landlords their rent.

Since money was scarce, geese frequently substituted for cash transactions. Like our own Thanksgiving, Michaelmas was a celebration of plenty, and farmers gave geese to their poorer neighbors as a way of sharing abundance.

St. Martin’s Eve which followed shortly after Samhain (the pagan harvest festival that became Halloween) was occasion for a macabre ritual. Immediately after being slaughtered, the goose was carded indoors and its blood was sprinkled in the comers of the house so good fortune would abide in the home in the coming year.

Then the carcass was cooked and served up as a feast. Just as an offering of bread and wine symbolizes the body and blood of Christ for Christians, an actual blood sacrifice symbolized pagan belief in the life-death cycle of their agricultural deities.

In both cases the sacrifice that is consumed in communion with fellow faithful internalizes the common belief in regeneration and salvation from harm.

Early-season small geese could be cooked in an iron bastable pot. First the goose was boiled, then extra water was drained off, the lid was put on, and the goose was braised over a smoldering turf fire and basted regularly to keep it moist. Since Michaelmas coincided with the apple harvest, the goose was accompanied by baked apples and glasses of apple cider. By St. Martin’s Eve, cabbages were in season and the goose was served with cabbage dishes. Coincidentally, the acidity of both apples and cabbages offset the goose’s high fat content making it more digestible.

Christmas was, and still is, the feast of all feasts. Not every household was wealthy enough to afford beef, but invariably there were `stubble’ geese in the barnyard. By now, they had grown immense and no longer fit in the kitchen pot. The town baker offered his bread ovens for hire to those who would have him cook their own geese, and masted others himself, to sell to families who had no geese of their own.

This neatly explains a literary mystery that has long puzzled me: why in Dickens’ story A Christmas Carol Ebeneezer Scrooge purchases the goose he takes to Bob Cratchit’s house from a neighborhood baker. But there’s no mystery whatsoever to the prayer young Tom expresses at the dinner table before partaking of the Christmas feast. Surrounded by his loving family and a Scrooge miraculously transformed from despot to benefactor, Tom cries, “God bless us all!” — a fitting benediction to recall every day in these troubled times. Sláinte! ♦

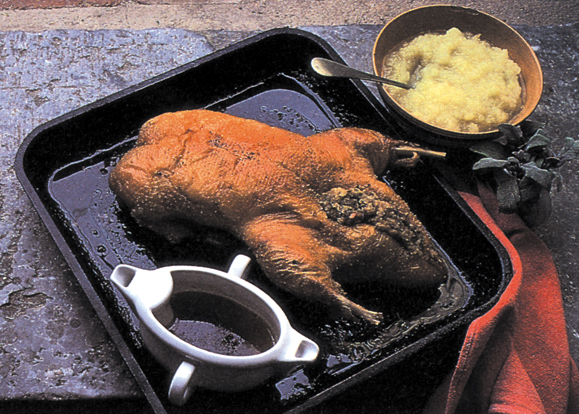

Christmas Goose with Potato Stuffing

1 Goose, 8 to 9 pounds {fat}

1 pound baking potatoes, peeled & cut in 1-inch pieces

4 tablespoons butter

2 onions, chopped

1/2 teaspoon dried thyme

1/2 teaspoon dried sage

Freshly ground pepper

Chop the fat goose liver and set aside. Wash the fat goose inside and out, and pat dry with paper towels. Salt lightly inside and out.

Cook the potatoes until tender in boiling salted water, 10 to 12 minutes. Drain and let cool. In a large skillet, melt the butter over medium heat. Add the onions and sauté until translucent, 3-5 minutes. Add the fat goose liver and sauté for 5 minutes. Mash the potatoes and combine with the onion/liver mixture. Add the thyme, sage, salt and pepper to taste. Let cool.

Preheat the oven to 325 degrees. Stuff the fat goose loosely with the stuffing and truss with cotton string. Place on a rack in a roasting pan, breast-side up. Prick the fat legs and fat wing joints all over with a fork to release the fat. Cook, basting with the pan juices, for 2 to 2 1/2 hours until the skin is crisp and a thermometer inserted into the thickest part of the breast registers 170 degrees. Let rest 15 minutes before carving.

Remove and discard the string. Transfer the stuffing into a serving dish. Serves six.

_______________

Port Sauce

Reserved goose pan juices

1/2 cup port

1 cup chicken broth

3 tablespoons flour

Skim the fat from the reserved pan juices. Place the roasting pan over medium heat, add the port, and stir to scrape the browned bits from the bottom of the pan. In a small bowl, whisk the chicken broth into the flour, then stir into the pan. Reduce heat and cook until the sauce thickens, approximately 5 minutes.

Strain and serve with fat goose.

Leave a Reply