In my father’s town, Carndonagh, County Donegal, Ireland, market day still goes on in a muddy field, behind “the diamond,” the town center, a ritual preceding memory. I walked down to it just the once, because he wanted me to see it.

Young cows and bullocks and sheep and pigs mill about in the damp, gray early morning. The steam rising from their manure piles and urine puddles put out a rich odor overpowering the incense of cigarette smoke and the taste of peat in the damp air. I didn’t stay long. I didn’t know it then, that this collection of men in their ancient work caps, trousers tucked into rubber boots, bargaining quietly in their musical brogue are history, not recreating, but ongoing.

My mother’s people, a Doherty clan, also are of the Isle of Doagh. In the little museum that was a Protestant church I once studied a map drawn in the 1600s, when the Duke of Chichester was charged with administrating these northernmost unruly fields and people. The Duke could not have been a favorite of the English King. On it is lettered “Fighart, land of Doherty.” Before the sand bar was vomited up by the sea in the late 1800s, creating a “road to the isle,” Fighart was desolate and isolated. It is still almost barren, bare of trees which cannot grow because the wild winds of the raging Atlantic which enfolds it will not allow it.

I call my mother’s people “the fish people” because of the whiteness of their skin and their hair of the palest blond or red, but more, because of their eyes, so little pigmented are they with blue or gray. Only I of the six siblings am of my father’s people, dark and of Spanish blood.

My cousin Paddy did not marry. He rarely set foot off the Isle of Doah. His sisters and brothers went early to England to make a living. As soon as they could, most came back to Donegal or to the town, but only one back to the Isle. Paddy grew a couple of cows and grazed a few sheep, kept a pig a year. He had chickens and a root garden and for sweetness, the berries like our blueberries that grow wild. Sometimes, on a dark night when he knew they hovered serenely under its surface roil, he would pluck silver salmon from Trowbreaghy Bay. He lived with his mother and father until they died and then stayed on that spit of land that rolls down to the Bay and beyond which Malin Head rises up against the Atlantic.

“Did you ever want to see Dublin, Paddy? Or come visit America?”

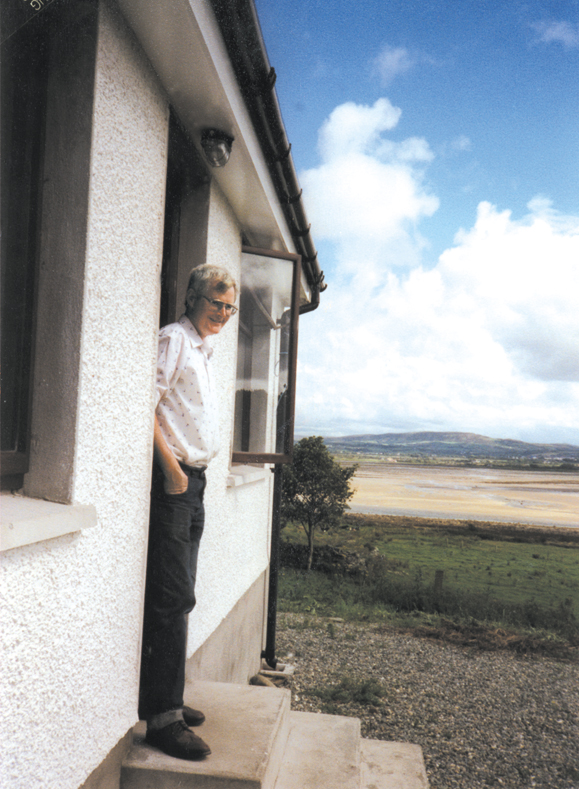

“Sure, why would I ever leave the Isle? I have everything a man could need. Why, this is a bit of heaven. Did you ever see a more beautiful sight?”

He would smile at us Yanks, and fling out his arm, presenting his view to us as a rich man would display his gold, for our admiration, and what he said was true.

On Market Day, last week, Paddy went into Carndonagh with two bullocks, stood leaning on the fence in talk with a neighboring farmer. A truck drew up, the fellow lowered the tailgate, and among the few young bullocks he let into the enclosure was one who had a yen for freedom. He made a desperate dash for it, straight through Paddy and his companion. His friend is fine, such things are common events on Market Day in Carn, but Paddy went down with great force, striking his head and never again becoming conscious.

For sure, Ireland in its remote regions is a place left behind by time — when we fly to Ireland it is that Ireland we seek. Of all my Irish cousins, Paddy was the truest link with what was.

They have harvested the organs of the young man Whose flesh and blood and soul had their origin, literally in centuries on this piece of land.

I wonder, will those who get life from his flesh, in their mind’s eye ever see the long-held view of the Bay, taste the peat smoke in the clean salt air of Fighart, experience the flashing arc of leaping salmon on a moonlight night. Will they inherit with his substance the essences that are centuries bred into Paddy as were his pale skin, his red-blond hair, his eyes of silver-blue? ♦

Leave a Reply