Brian Rohan visits Croke Park and finds it utterly changed, except for the heartbreak.

℘℘℘

Twenty years ago, it seemed only politicians and priests had plastic molded seats. Twenty years ago, under-12s were thrown over the turnstiles, no tickets necessary. And 20 years ago the concession stands definitely did not sell “Chicken Tikka on Pita Bread.”

From my seat behind the Canal End goalposts, it seemed the only thing Croke Park 2001 has in common with Croke Park 1981 is the potential to break your heart.

As the international headquarters of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), Croke Park is home for the indigenous Irish sports of huffing and Gaelic football. Located on Dublin’s Northside, it has been the setting for almost every GAA championship since before the founding of the Irish State. It has no parallel in American team sports, whose championships are played in different stadiums and cities every year. If your team is traveling to play “Croker” in the autumn, you know you’re in for a big day.

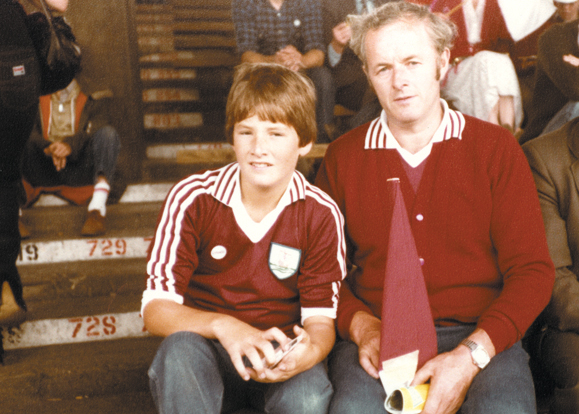

This was first explained to me early on a Sunday morning in September 1981, as we drove east from Galway to Dublin. In parts of rural Ireland, the GAA is a cult, and our family worships the ancient game of hurling (there are references to the sport in pre-Christian writings). It is a whip-fast combination of field hockey and gang warfare in which your team of 15 heroes bash 15 others (and a leather ball) with wooden sticks.

The cult works like this: If you suffer enough rainy Sundays along sidelines in Athenry, Ballinasloe and the west Bronx, your 15 hurlers might just bash through to the final. And you might be lucky enough to find yourself in a car one Sunday morning, on the way to Croke Park. Forget about Lourdes, Medjugorje and Knock — a September Sunday in Croker will cure what ails ya.

To a young “Yank” like myself in 1981, the importance of the trip was initially difficult to comprehend. We had moved to my parents’ native Galway from New York earlier that year. The relocation was motivated in part by their love for Galway hurling, a love perversely strengthened by the annual failure of Galway hurling. Like the Boston Red Sox or the Chicago Cubs, Galway hurling’s pre-1980 hopelessness — only one All-Ireland victory ever, in 1923 – made its devotees that much more psychotic.

The devotion to one’s county team is heightened by the fact that the GAA’s athletes are amateurs. My American sporting heroes — Graig Nettles, Bucky Dent and Reggie Jackson of the New York Yankees — were millionaires whose homes were far from my own. But the superstars of Galway hurling are farmers and builders, uncles and cousins. When they traveled to play games in New York they didn’t stay at the Plaza, they stayed at our apartment. So supporting the home tribe meant more than just cheering for the shirt.

So why was the Galway team so unfortunate? Every year they had decent teams, and every year they failed. Bostonians accept that the Red Sox are doomed because they sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees. The accepted legend in our house was more metaphysical: Many years ago, the Galway hurlers were running late for a Sunday game, so they decided to leave Mass early. Since then, we were told, the team was cursed. Cursed!

Finally, in 1980, the curse was broken. In the parish hall of a Bronx Catholic church, we listened to Croke Park erupt. In those days GAA-crazy immigrants gathered round loudspeakers hooked up to a telephone. At last! Galway had won the All-Ireland at Croke Park. Was it the start of a new dynasty? My folks, perhaps fearing another heartbreak, were not at Croke Park to witness the event — they were stuck on the wrong side of the Atlantic.

Less than a year later, by an amazing coincidence, the moving vans arrived outside our house.

The following September, dreams of a dynasty were quashed. In the concrete stands, I watched tears fall from the eyes of my grandfather, my uncles and my parents, as Galway was beaten by a neighboring county, Offaly. We shuffled out of Croke Park and reconvened at a nearby pub, which was to have hosted the victory party. A roomful of farmers sat with pints of Guinness in absolute silence, as if mourning a death. When a neighbor stood to sing “Green Fields of France,” the farmers erupted in tears. A heartbreak had once again come down from Croker.

Over the next two decades, I would learn more about Croke Park. The 14-acre site has been used by the GAA since the late-1890s, eventually taking the name of one of the Association’s early patrons, Thomas William Croke, a Tipperary Archbishop. The stadium was a center of sorts for the cultural and political revolution taking place in what was still British territory. “Foreign sports” like soccer and rugby were (and still are) banned from Croke Park, in the interest of re-birthing ancient ones like hurling and Gaelic football.

The 1916 Easter Rebellion failed to free the country but it did provide better viewing for Croke Park match-goers, as the bombed-out rains of what is now O’Connell Street were dumped at one end of the playing field to build a sloped spectator terrace. To this day that affectionately loved terrace — the standing-room-only equivalent of the bleachers at Wrigley Field — is called “Hill 16.”

“Bloody Sunday” put Croke Park on front pages around the world in 1921, during the War of Independence. Angered by assassinations carded out by Michael Collins’ IRA guerrillas, the British Army’s Black &Tans invaded Croke Park on the day of the Gaelic Football Final, guns blazing. Thirteen were killed, including the Tipperary captain Michael Hogan. A seating area built in 1924 was named “The Hogan Stand” in his honor.

Seven decades later, after years of sporadic Croke Park building, Ireland was stuffed with Celtic Tiger cash. Tens of millions of pounds were spent in the 1990s renovating and modernizing the park. The result is a massive blue-steel stadium that resembles a modern sports complex in American suburbia. The Cusack Stand, built in 1937, has been replaced by the 25,000-seat “New Stand,” complete with 47 “hospitality suites.” Publicity material boasts: “The premium level contains excellent facilities such as restaurants, bars and conference areas, all of which contribute to making this new development one of the most impressive stadiums in Europe.”

Picture Credit: Ray McManus/SPORTSFILE

Other areas are still being rebuilt, and the concrete terraces I first sat on in 1981 have been fitted with molded plastic seats. The new seats are comfortable but limit the stadium’s capacity: kids are no longer allowed in free, to squeeze in next to their fathers. The all-time high attendance for Croke — more than 90,500 adults for the 1960 football final — will never be matched again. In three years, when construction is scheduled to finish, attendance will be capped at just over 79,000.

Many of the changes are welcome, especially the excellent GAA museum that houses memorabilia, records and interactive displays. But long-time fans have complained that Croke Park has gone too far, as evidenced by the number of corporate-held seats and escalating ticket prices. The 10,000 denizens of the standing-room-only Hill 16 section have reacted angrily to rumors of an invasion by plastic bucket seats.

Most disturbing to some is the apparent plan to sell off hallowed areas to corporations. In the same way that Denver Broncos fans resist the change from Mile High Stadium to Inesco Field, GAA fans have denounced plans to attach corporate names to the rebuilt Cusack, Hogan and Nally stands. The names attached to Croke Park areas and also GAA trophies mostly derive from the names of long-dead Irish rebels — some fans have accused the GAA of a plot to cleanse Croke Park of any such Fenian names, to make the GAA more acceptable to the Celtic Tiger.

And what about the food? The independent fan website An Fear Rua, a popular base for criticism of the new Croke Park, issued the following attack on, among other things, the Chicken Tikka: “One imagines they eat nothing else in the Homes of Tipperary and the Hills of Donegal. Is it any wonder, in a country which is nowadays awash with money, that the wonderful institution of the flask of tea and the `hang sangwiches’ consumed off the bonnet of the car, is still widely observed at GAA venues all over the country?”

What of the heartbreak, then?

This season, as the Galway hurlers bashed their way into another post-season, I was back at Croke Park with family members who were there in ’81. We jumped for joy at the semifinal, when Galway managed an astonishing upset by beating the defending champs, Kilkenny.

Then, of course, came the final. On yet another beautiful Croke Park Sunday in September, the Galway hurlers were crushed in the All-Ireland final by Tipperary. For the fans, there were tears, beers and a familiar drive home — back out, once again, into the west.

Thankfully, some things remain the same. ♦

Leave a Reply