Elizabeth Frances Martin talks to artist Elizabeth O’Reilly.

“At first, it was hard for me to paint back in Ireland. Once you have left a place, it can be painful to return. It took me many years to break that barrier.” Growing up as the second youngest of nine children, Irish-born artist Elizabeth O’Reilly determinedly managed to fit painting into her life from the very beginning. With a family home down in West Cork, summers were spent by the sea, and O’Reilly developed a passionate commitment to capturing the land around her on painted board.

Driven from the start, after graduating with a teaching degree in 1978, she taught school in Dublin while taking evening art classes at NCAD. In 1986, she and her future husband decided to join the many Irish then immigrating to the United States. Married and ensconced in Brooklyn, O’Reilly taught school in New York, entered the Brooklyn City College MFA program and graduated in 1992.

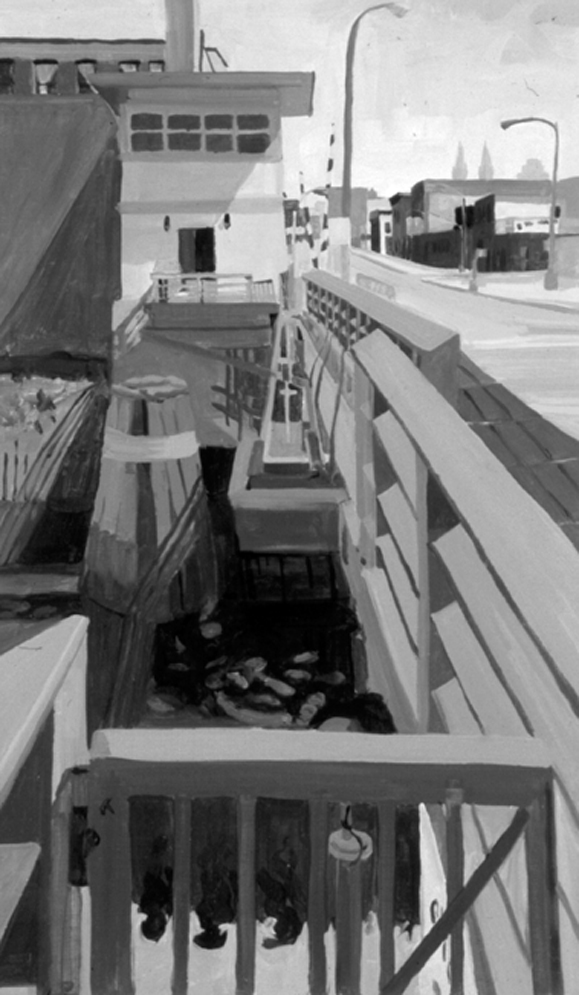

O’Reilly’s work has been exhibited widely throughout the United States and Ireland. She is an enthusiastic recipient of numerous artistic fellowships and residencies, including a particular favorite, the Ballinglen Foundation in Ballycastle, that enables her to spend extended time painting in the west of Ireland four or five times each year. Her regular haunts include Counties Mayo, Clare and Donegal. When she isn’t traveling, this earnest and ebullient artist is likely to be found working in the industrialized area alongside the Gowanus canal in Brooklyn, hardly a typical painter’s pastoral respite. “With the Brooklyn work, I see a familiar thread that reaches back to many of my Irish paintings. This area has fallen into disuse, and I find myself painting vestiges of the past, things that have been discarded. What intrigues me is seeing nature take back the bridges, the weeds coming through…I love the canal’s man-made colors, especially the strange greens and bright blues of Carroll Street.”

With an upcoming show at the George Billis gallery, located in Manhattan (November 6 — December 8), and representation overseas by the well-esteemed Taylor Gallery in Dublin, the recognition factor attached to O’Reilly’s name in artistic circles is definitely on the rise. Most recently, she was the subject of a documentary film sponsored by the Arts Council and TG4, the Irish language channel, titled, `Ealaiontoir Thar Saile, An Artist Abroad.’ The October 2001 Cork film festival debuted the piece and it is scheduled for broadcast on TG4 in January 2002. The film takes a collage-like approach to recording O’Reilly’s work process by juxtaposing footage of the artist in action with closeup shots of the finished, painted compositions. In essence, the director’s vision enables viewers to look at landscape first from their own perspective. Then, by focusing on the actual painted image, the viewer is invited to try and glean an insight into O’Reilly’s particular vision. “When working outdoors, I am very careful about how I decide what I’ll be painting. I’m completely absorbed and focused. I find myself looking and looking, and all of a sudden, I see what interests me and I’m ready to paint. Where some people might see a beautiful beach, for me, that beach become shapes, forms and colors that I’m trying to capture and put together both formally and emotionally.”

Bordering between realism and abstraction, stylistically, O’Reilly’s work resists easy classification. Never one for exact mimesis, she persistently delights in pushing herself to simplify and abstract from nature. “The more I can consciously eliminate details and distill reality, the more successful it is to me.”

O’Reilly is reputed for thoughtful and carefully wrought paintings that evoke an intangible spiritual essence of Irishness. Her paintings often hint of loss, the transitory nature of life and the unique historical relationship that exists between Ireland and the land. In talking about Dunpatrick head, a favored destination for the artist, O’Reilly recounted, “I go there often, no matter what the weather is, it is always beautiful. All I need is for the light or the weather to change and things can get pretty wild out there…I’m interested in seeing and capturing how things change, things so often are not what they seem.”

Undoubtedly there is an emotional connection between the artist, her subject matter, and her manner of representation. For O’Reilly, an initial emotional connection that frames her work may quickly become a concentrated exercise in formal concerns. This visual transformation is made manifest in some of her Irish paintings that refer to the concept of leaving Ireland, which are based both on her personal experience and those of the well documented waves of Irish leaving that continued through the 80s. “The fact that I’m an immigrant informs my work, I can see it in my choices as to what I paint, what draws me in and attracts me.”

O’Reilly’s work can be positioned within the long tradition of Irish painters drawn to the west for inspiration. Never one to idealize or invent for the purposes of a pretty view, O’Reilly’s vision of the west captures the inherent, natural beauty of Mayo which even today resonates with the palimpsest scars of the famine. “I see history everywhere in the landscape, even in the potato drills on the field. That formation may look like a pattern to an outsider. However, to an Irish person, that `pattern’ may signify the collective emotion of these large, numerous families that were so desperately dependent on a crop, and the horror of the devastation that followed…I’m fascinated and awestruck by the landscape in Ireland, it’s amazing and wonderfully wild. By attempting to paint what I see around me, I feel closer to both the history of the country and my own history.” ♦

Leave a Reply