On July 1st, 1920, my grandfather saved the only no-hitter ever thrown by the Hall of Fame pitcher Walter Johnson. Grandpa played first base for the Washington Senators, and he and Johnson were in Boston to play the Red Sox. When the ninth inning came around, only one Red Sox had made it to first base – on an error – and the Senators were ahead 1-0 with two outs. One more out and Johnson would have a no-hitter.

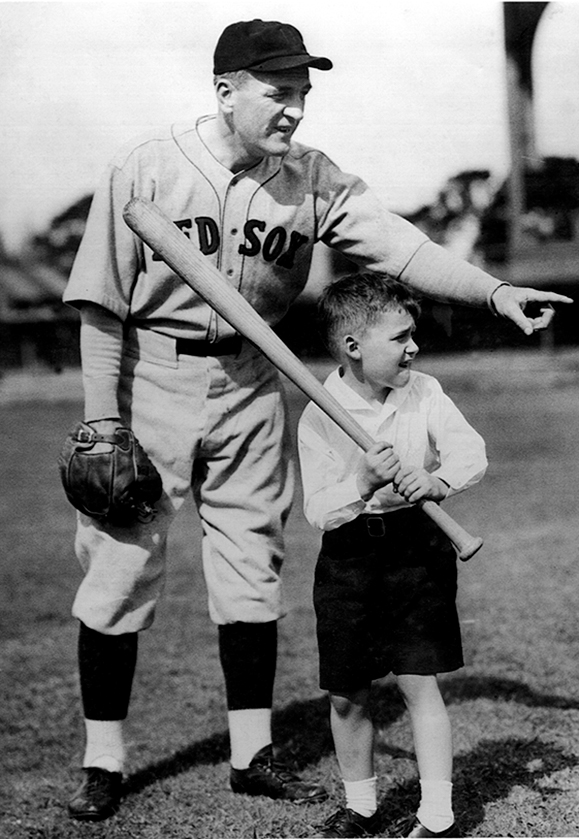

Red Sox outfielder Harry Hooper, left-hander, came up to bat. On Johnson’s second pitch, Hooper pulled the ball towards right field. The ball bounced in front of first base, and appeared to be headed for the outfield when it was stopped by first baseman Joe Judge. As sportswriter Ira Smith described it, Judge “broke to his left as soon as the ball left Hooper’s bat” and “with an almost superhuman effort, he threw himself headlong toward the oncoming ball.” The ball hit Judge’s mitt. While on his back, my grandfather tossed the ball to Johnson, who was covering first, for the final out.

This story and the others about Grandpa’s remarkable 36-year career in Washington baseball are common legend in my family, but whenever it comes up – usually this time of year, World Series time – there’s always a similar rejoinder. One of my brothers or my sister or a cousin will shake their head and say it: “Joe Judge should be in the Hall of Fame.” Everyone will nod in agreement, followed by quiet cursing: those idiots in the Hall of Fame – banning a player of his stature just because of one dumb article.

It’s probably the most quiet scandal in the history of sports, but my grandfather is not in the Hall of Fame because of an article he wrote in 1950 for Sports Illustrated. It didn’t hurt that he was a quiet, unflashy man who didn’t hit a lot of home runs. The closest he got to being Hollywood was when he became – and this is not provable, but I’m certain of it – the inspiration for the character Joe Hardy in the play Damn Yankees.

Although not a flamboyant personality, my grandfather Joe Judge, the son of Joseph Patrick Judge, a farmer from County Mayo who came to the States in 1883, was a brilliant baseball player. In his 18 years with the Senators, 1915-1932, he batted over .300 for nine seasons, led or tied the American League in fielding seven times, hit safely 2,350 times and stole 212 bases. Until 1955 he held the American League record for assists by a first baseman. His lifetime batting average was .298. In 1924 he was on the only Senators team to win a World Series; that same year Babe Ruth named him to his All-American team. Taking into account his years coaching at Georgetown University after he retired from the game, he gave 36 years to baseball.

As for stamina, iron man Cal Ripken has nothing on Judge. Who’s Who in Baseball put it this way, “as a member of the Senators Judge became one of the most popular players that ever wore a Washington uniform. He covered first base through the administrations of Presidents Wilson, Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover.” Until 1990, when tied by George Brett, Louis Wilson and Frank White, he and Sam Rice topped the list of Most Seasons as Teammates – 18. Up to his death at 68 in 1963, a year before I was born, he was known and recognized by virtually everyone in Washington. At a 1953 Old Timers Game, Mel Allen introduced him as “that other Washington Monument.”

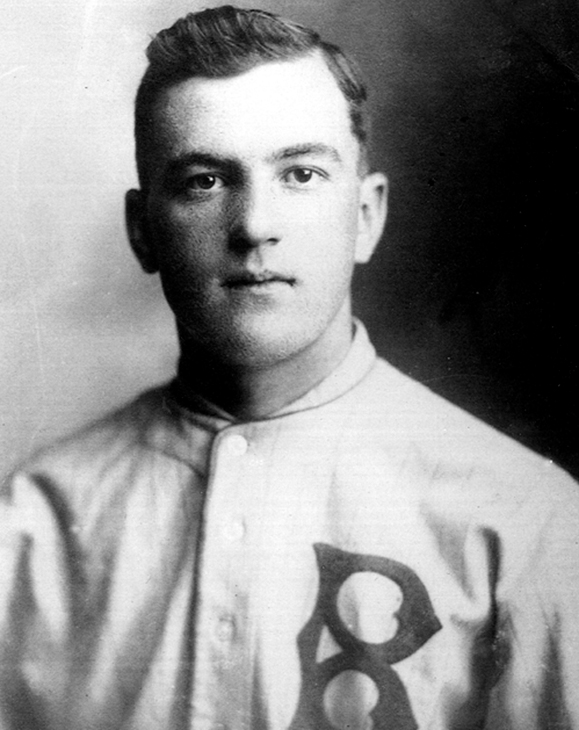

Joe Judge’s career began in 1915, when Senators owner Clark Griffith had traveled to Buffalo to scout a promising center fielder named Charles “Kid” Jameson for the sum of $7,000. After seeing the Bison in action, Griffith insisted that the “young first baseman ought to be thrown in the deal.” Griffith got the 19-year-old Joe Judge for free. However, the Washington papers soon caught wind that a “sensational” young first baseman was going to be playing for the Senators. On September 20, 1915, Judge arrived in Washington on a late train. Umpire Ollie Chill decided to hold up the game for ten minutes so as not to disappoint the fans. In that first game, Judge had two hits and two RBIs.

Grandpa spent most of the rest of his life in Washington; 18 years with the Senators, two with the Red Sox in the twilight of his career, and 19 coaching at Georgetown University. Until recently, his daughter, my aunt Anita, still lived in the house he bought in Chevy Chase, Maryland. She is now in an assisted-living home, but she remembers the Senators’ victory in the 1924 World Series, when she was five years old. “I remember that parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. They went to the White House. Old Calvin Coolidge had his picture taken with them and somebody, I think it was the Hecht Company, gave them all clothes. They went in and got a suit for free. And they’d go into a restaurant and try to pay the bill, and forget it. It was free. I mean, they were treated like royalty. We went to the theater – in those days they had vaudeville. They stopped the vaudeville, stopped everything, put the spotlight on where we were sitting and introduced him.”

He deserved it: he hit .385 in the Series.

Anita also remembers when Griffith Stadium held Joe Judge Day on June 28, 1930, when all ticket proceeds went to the first baseman. Giving a player a day was rare back then, but enough fans showed up to net $10,500. According to the June 29, 1930 edition of the Washington Post, Grandpa Judge was “Showered with coin and gifts totaling $8,000.

“Now Joe Judge knows how highly esteemed he is by Washington fandom. The fans made his day – Judge Day – something long to be remembered in baseball history. Orators praised him. Friends showered him with gifts and the contending clubs contributed handsomely to the purse presented to the player. It was a big time all around.”

After the game the other players brought over a three-tier cake that was so massive they couldn’t fit it through the front door of the house.

Like everyone else who knew him, his daughter Anita describes him as a man who quietly “put his heart and soul into the game” but could be considered “dull” compared to flamboyant types like the Babe. Still, he managed to grow agitated when he wrote a piece for Sports Illustrated in 1959. Titled “Verdict Against the Hall of Fame,” it claims that “the Hall has lost some of its meaning and much of its glory in recent years.” Grandpa Joe slammed players like Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers and Frank Chance, who were immortalized for the poetic ring of their double-play combination (Tinkers to Evers to Chance), and wrote that “Ballads…do not make base hits.” (Tinker’s lifetime average is .264, Evers’ .270). He pointed to other lousy Hall of Famer’s records such as catcher Ray Schalk, lifetime .253, and shortstop Rabbit Maranv who never hit over .300. He blasted players whose behavior superseded their talent: “To be a credit to the game of baseball, a man need not have got off a record number of wisecracks or assembled a record number of feature stories. There are a lot of colorful palookas.”

He went on: “In my day, by the time the infield was finished spiting tobacco juice and licorice and rubbing the ball down with mud, especially on a dark afternoon, that ball would come at you looking like a lump of coal. A great hitter would lay the wood on it regardless of the side it was thrown from or of the stuff on it.

“That same man could steal the base that made the difference. He was fast enough so that the hit-and-run and bunt-and-run were always possible. And when he got back to his position he would come up with the great catch, the great save, the great throw that meant winning instead of losing.

“Today many of the so-called sluggers couldn’t steal a base if they were alone in the park. They are not expected to throw too well or run too fast as long as they can belt the ball out of the park when their one moment of usefulness arrives.

“The idea of being a team member sometimes is lost completely, and what we have is an association of specialist businessmen all investing their specific talents and carefully watching their own special interests, upon which they hope to declare a dividend the following year.”

It’s long been an open secret in the family that my father, Joe Judge’s son and a journalist who worked at Life magazine and went on to National Geographic, was the author of the Sports Illustrated article. The piece does seem too combative for the man everyone describes as low-key. My father was an Irishman who loved a good argument, and his fingerprints are all over the essay. He also used to talk about how Grandpa could have been held back from the Hall and more fame and fortune by the fact that he wasn’t a home run hitter. The rise of home run hitters like the Babe in the early 20s could have overshadowed a more consistent, day-to-day player like my grandfather, who, like other Senators, had a tough time sending balls out of Griffith Stadium. The year the Senators won their first World Championship in 1924, during the regular season they hit one home run in 77 games at Griffith Stadium and it was inside the park. Joe Judge only hit 71 homers, but in a different park, that figure could have easily been double.

Like many old timers, Grandpa’s season fizzled out with an injury and not much fanfare. On May 1, 1931 he took himself out of a game in Boston, and had his appendix removed the following day. He was 36, and the operation effectively ended his career in the majors. He bought a restaurant, Joe Judge’s, which he took no real interest in and sold in the early 40’s. Then he took a job coaching ball at Georgetown University, a job he grew to love. But it didn’t last forever: in 1959 he was forced to retire because he hit 65.

By then baseball had changed. Games were broadcast on television. Grandpa could watch from home and avoid going to Griffith Stadium, which depressed him. My father used to say that towards the end of his life Gramps was exactly like the crotchety old man watching the Nats losing in the beginning of Damn Yankees – razzing the players on his TV and trying to show the generation that pushed him out how to play the game.

In fact, there is compelling evidence that “Shoeless” Joe Hardy, the main character in the late Douglas Wallop’s The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant, which became the show Damn Yankees, is based on my grandfather. Wallop dated and almost married my Aunt Dorothy, Joe Sr.’s youngest daughter, in the 1940s, and she recalled that “he loved baseball, and was steeped in Senators’ history.” For hours he would exchange anecdotes with Joe. (Although she admits Wallop gathered books full of information from her father, Dorothy doesn’t believe that Joe inspired the character.) There are some odd coincidences. Both characters share the same name, and in the film Joe mentions to the other players that he has just “rented a place in Chevy Chase,” where Joe Judge lived. The Devil in Damn Yankees marks September 24, my birthday, as the day Joe must relinquish his soul.

Joe Judge died in 1963, when he suffered a heart attack while shoveling snow. Sportswriters mourned the loss of what one called “the Senators’ all-time great first sacker.” But by then he was largely forgotten. The Senators were about to be moved, JFK was in the White House, and the Beatles invasion was just a year away. The age of celebrity was beginning, and there wouldn’t be any time for a player like Joe Judge. It’s too bad he didn’t get drunk more or maybe get arrested. His reticence, and his one flash of anger captured in print, buried his name. To the shame of the Hall of Fame, it might stay that way forever. ♦

Leave a Reply