The evolution of Martin McGuinness – from high school dropout and IRA man to political leader seeking an end to violence and, finally, his emergence as Northern Ireland’s Minister for Education.

If it’s fair to judge the effectiveness of a politician by the depth of his opponents’ dislike for him, then the Sinn Féin MP and Assemblyman for Mid-Ulster, Martin McGuinness, must be a very effective politician indeed.

Even more than Gerry Adams, McGuinness appears to drive unionists, as well as British conservatives, into a frenzy of irrational rage. The Ulster Unionist security spokesman, Ken Maginnis, now Lord Maginnis of Drumglass, once called him the “terrorist godfather of all godfathers.”

The blue-eyed McGuinness appears totally unfazed by this barrage of criticism. A buoyant self-confidence protects him like rhino-hide. Which is just as well. If he had a tendency to self-doubt, he’d be in a psychiatric ward.

What is often overlooked when people take sides over his personality and his contribution to the last 30 years of Irish history, are his undoubted skills as a negotiator, administrator and communicator.

The stereotypes “McGuinness the Mop-Top Boy General” and “McGuinness the Brutal Gunman” can obscure the reality that he is a self-taught, purposeful and formidable politician – arguably the most sophisticated in Ireland.

The stereotyping also denies him the right to be human. A devoted family man and non-drinker (the most he would enjoy would be a glass of red wine once every two or three months), he spends every available moment with his family at home in Derry.

In May this year [2001], when he announced he would be giving sworn testimony to the Bloody Sunday Tribunal (as the IRA’s second-in-command in the city at the time of the killings) there was a torrent of abusive invective in the British press.

The London Times thundered “his journey from apprentice butcher to Minister for Education is spectacularly bloody. And he knows it. He graduated with amazing speed from supplier of sausages to Bogside families to the director of a devastating terrorist campaign.”

When he was appointed Minister for Education in the Stormont power-sharing executive, another British paper called it “a form of political child abuse.”

Born in 1950 in Derry’s Bogside, where there was cross-generational poverty, unemployment and discrimination, he still lives in the area, in a rented terrace house with his mother living just around the corner.

He attended the Christian Brothers’ “Brow of the Hill” primary school. “Most of the teachers were good and decent people, but there were one or two who were extremely aggressive and hostile. Those who were bad were mental, to tell you the truth,” he says.

In 1965, the young McGuinness went for a job as a garage mechanic. He says the interview consisted of two questions: “What’s your name?” and “What school did you go to?” After the school’s name labeled him a Catholic, it was “Out the door.” It’s been called the most expensive rejection in Irish history.

He went on to work as a butcher’s assistant in the city but, in August 1969, he was among the hundreds of young Catholics from Derry who picked up stones and petrol bombs and engaged the RUC in the epic `Battle of the Bogside.’

But the blatant job discrimination didn’t make McGuinness a republican, that came after the 1969 beating to death of Sammy Devenney in his own home, and the 1971 RUC shooting of two young men, Dessie Beattie and Seamus Cusack, close to McGuinness’s home – two deaths he still recalls frequently.

McGuinness watched as 21-year-old Beattie bled to death at the bottom of his street, in a city where gerrymandering and systematic discrimination had corralled an entire community into a deprived and excluded ghetto outside its walls.

Within a year he is said to have taken effective control of the IRA’s Derry Brigade (after many of its leaders were interned without trial) through determination and sheer force of personality.

An informer who was a member of the Derry IRA at the time later told a British newspaper, “He demanded total commitment and support from subordinates, and he got it. He wouldn’t say a lot at meetings, but he was very quick to grasp the key points.

“And believe me, once he’d made up his mind. that was it – he might be all smiles but nobody ever crossed Martin twice.”

According to Tim Pat Coogan’s book The IRA, McGuinness was involved in the targeting of Derry’s commercial heart, making it look as though it had been “bombed from the air.”

Unlike the IRA campaign in Belfast, however, there were few – if any – attacks with loss of civilian life. One activist at the time recalls that, if McGuinness was worried about possible non-combatant fatalities, he would abort an operation rather than take a risk.

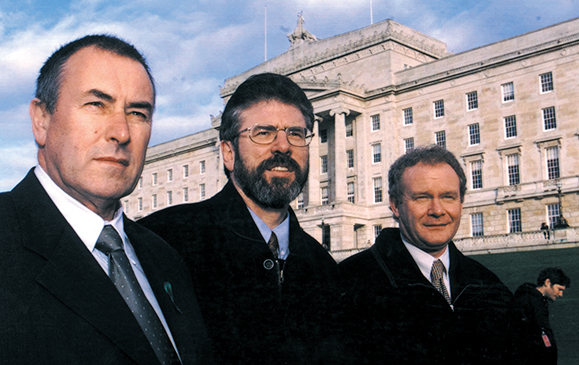

In 1972, five months after “Bloody Sunday,” he was part of an IRA delegation (which also included the young Gerry Adams) that was secretly flown to London for talks with the then Northern Secretary, Willie Whitelaw.

The IRA gave the British three years to get out. They were shown the door. On the RAF flight home, the M15 officer, Frank Steele, who had helped arrange the talks, engaged McGuinness in conversation to see if there was any political flexibility.

McGuinness told Steele that in order to come to “a sensible agreement with the unionists, the IRA would first have to get rid of the British.” The way to do that, Steele remembers him saying, was by violence. “As proved all over your empire. You will get fed up and go away.”

McGuinness was arrested across the border in Co. Donegal six months later and charged with possession of 250 lbs. of explosives and 4,757 rounds of ammunition. In court he admitted IRA membership.

“For over two years I was an officer in the Derry Brigade of the IRA and very, very proud of it,” he said. “We firmly believed we were doing our duty as Irishmen.” He got six months.

He was one of those fortunate individuals who, while they can hardly be said to have enjoyed prison life. did his time in jail relatively easily. He was convivial and an accomplished, if competitive, foot-baller. It didn’t gnaw at his soul, although he missed his family dreadfully.

Having served his time, he returned to the front line before being arrested again across the border in 1974 and sentenced, a second time, for IRA membership. He got 12 months.

Also in 1974, he married Bernadette Canning, and subsequently became father to two girls and two boys. He is now a grandfather, of Tiarnán, a two-year-old boy. The McGuinness family remains very close and very private.

Back in the 1970s, despite his growing family, McGuinness’s involvement in the republican movement continued uninterrupted. He is believed to have become the IRA’s chief-of-staff and also rose through the Sinn Féin ranks to become its lead negotiator in secret talks with the British in the early 1990s.

It was McGuinness whom the MI5 officer, Michael Oatley, secretly met in Derry in 1991 in the encounter that marked the beginning of the peace process. “I thought him very serious and responsible and I didn’t see him as someone who actually enjoyed getting people killed,” Oatley later said.

“I found him a good interlocutor – rather like talking to an army officer in one of the tougher regiments like the Paras or the SAS.” The subsequent secret contacts between MI5 and the IRA’s Army Council that ultimately led to its ceasefire were also conducted through McGuinness.

After the ceasefires and the talks leading up to the Good Friday Agreement and the setting-up of the Stormont power-sharing Executive, McGuinness was made Minister for Education – a job he is widely regarded to have performed exceedingly well.

His department is now undertaking a major consultative exercise on what, if anything, should replace the “Eleven-Plus” examination, which streams children into academic tiers prior to second-level education, and which former ministers preferred to ignore as a political hot potato.

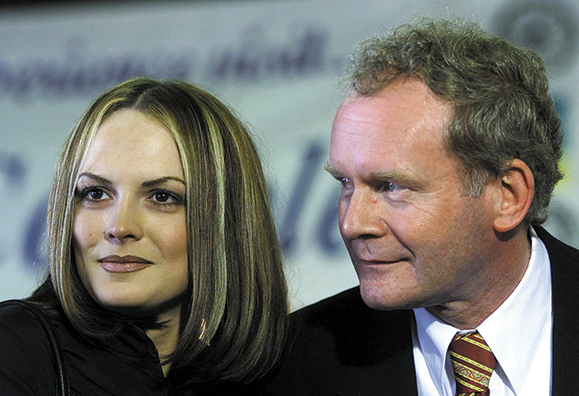

After June’s stunning increase in the majority he commands in his Mid-Ulster constituency (multiplying it five-fold), he was photographed with his daughter, Grainne, a strikingly beautiful young woman. A rare corner was lifted on McGuinness’s private life and there was considerable surprise expressed in some quarters, indicating a certain public prejudice, as though the children of Sinn Féin leaders should, in some way, be physically unattractive.

Whatever one’s views on his politics, few would disagree that the republican movement has been fortunate to have a politician of his shrewdness, determination and principles at its heart.

How did you feel when a lawyer for the British soldiers at the Bloody Sunday Tribunal, quoting an informer, claimed you had admitted firing the first shot?

It wasn’t a surprise. The British are capable of almost anything. I knew the focus would be on the British Army, on the Parachute Regiment, on Edward Heath (the Conservative British Prime Minister at the time) and that when the full truth emerged, they would come out of it pretty badly.

I knew they would stoop to every trick in the book to try and justify what the Parachute Regiment did. They would have to implicate republicans. Because I was the best known republican in the city it was always bound to come to my door. It was a very ham-fisted attempt to implicate me.

My first thoughts were for the relatives of the people killed on Bloody Sunday and the people of Derry, what would they think? But I needn’t have worried. They saw through it immediately, that it was nonsense and just the British grasping at straws.

The people of Derry are very intelligent and tuned-in and they quickly realized what was happening.

In May this year, you agreed to give eye-witness evidence to the Tribunal, as the second-in-command of the IRA in the city at the time. It was the first time a senior IRA figure had made such a public admission. Why did you do it?

I made the decision months ago. I settled in my own mind that I would, and wanted to, give evidence as a citizen of this city and as someone who was on the march. Almost immediately, I recognized that questions would be asked about what position I held on that day. In no circumstances was I going into the witness box to tell lies about any of that. It would have been a disservice to the people of Derry, to the families and to myself.

Did you seek the approval of the IRA?

No, that’s absolutely 100 per cent wrong. I discussed it with close colleagues and with my family and made my own decision. For me it can’t come quick enough. The sooner the better – I have no concern at all about who is questioning me on behalf of the British. I am looking forward to appearing at the Tribunal and telling the truth.

You are a Catholic, the church preaches against violence. How did you square that up with your role in the IRA?

Well, I look at the fact that the RUC went into the house of Sammy Devenney and beat him and he died of his injuries. I look at the fact that British soldiers shot dead Seamus Cusack and Dessie Beattie within 24 hours, both innocent Derry men.

There was massive violence being used to oppress the people of Derry yet there was no IRA in the city at that time. I saw myself as part of a people’s uprising, from children up to those in their 80s, involved in the making of petrol bombs and missiles that could be thrown at the RUC.

In the minds of us all, we were defending ourselves. It was the most natural thing in the world to do.

What about when there was no rush of events, when you had a chance to think about what you were doing? The Pope himself begged the young people of Ireland to turn away from violence when he visited Ireland.

I was in the Phoenix Park with my wife and daughter, who was two at the time, and I also heard very clearly what the Pope said in Drogheda. I was part of a struggle, so obviously decisions had to be made as to whether or not there was a justification for continuing to resist what the British were doing in this country.

Throughout many centuries in the world, there have been conflicts and there have been Catholic chaplains who have ministered to soldiers. I suppose in the end it comes down to whether you think in your own mind that it was a just struggle.

Did you ever have to wrestle with your own conscience?

Well, I think that anyone who has a conscience has to wrestle with it and rationalize and decide how to live their own life. In the course of the late 1960s we lived through a very determined effort by the British government to defeat the battle for equality, justice and civil rights.

We were faced with the British Army, the RUC and the UDR (Ulster Defense Regiment) – forces that were absolutely dedicated to defeating the struggle for freedom. As a young nationalist coming from an area like the Bogside, there were only two things you could do.

One was to sit there in the house and watch the television and never come out the door. Or go out onto the streets and be with the people struggling for their dignity and integrity.

Being part of that struggle, you begin the process of militarily, through violent means (for want of a better expression) opposing the forces of the state.

If you hit a soldier on the head with a stone, if you threw a petrol bomb and it landed between two or three RUC members – you decide that this is a just struggle and those people are wrong.

I recall vividly many elderly people infuriated at British raids on their houses, who would go to confession and would tell the priest how they had attacked the British Army, sworn at the British Army, thrown stones at the British Army.

They would then come out of church and say that the priest had told them that was fine.

Why did you not join the SDLP (Social Democratic & Labor Party – the other nationalist party)?

I didn’t see them as a united Ireland party or that they could accommodate the desires of the young people of my generation who believed the way forward was an end to British rule.

I believed then that, had nationalists been given equality, the SDLP would have settled down within the confines of what some people call the United Kingdom. I didn’t see my future there but in an independent, sovereign, 32-county republic.

If you were Minister for Health and, hypothetically, a law was passed allowing abortions to be carried out, could you administer that law?

Let’s be very, very clear. I am opposed to abortion as a means of birth control. If it were necessary to save the life of the mother, society has a duty and responsibility to face up to that.

But if there was a law that allowed abortion virtually on demand, as there is in Britain, would you resign?

I would have to go with my conscience. I am opposed to abortion. But this is not a Catholic thing, this is me as an individual. I don’t believe I have the right to shove that down anyone else’s throat but as a Minister I would have a massive difficulty with it.

You left school at 15, does that make being Minister for Education more difficult?

I had a very wide-ranging education after I left school. I often say I’m a graduate of UCB – University College, Bogside. I’ve effectively educated myself over the course of the last 35 years.

I really don’t like bullies at all, and the presence of those one or two at school was a very demotivating experience. There were some good, some mediocre, and some very, very bad teachers.

One teacher who was great was Seamus Deane (author of Reading in the Dark and currently Keough Professor for Irish Studies at Notre Dame University, Indiana). He was gentle, kind and never raised his voice at all, an ideal teacher who was very highly thought of.

I liked geography, looking at maps, learning about capital cities. We were a class of about 30, and some were interested in learning and others weren’t. I learnt that smaller classes are better.

Was the strap used at all?

Yes.

Was It used on you?

Maybe once, but what was worse was seeing it used on other boys.

What part of being Minister do you enjoy best?

Going to schools and meeting children.

Do you ever feel worried about your own security, visiting schools in Protestant areas?

Not at all. If you felt like that you would never leave the Bogside in the morning.

So you take a fatalistic approach?

No, not at all, I want to live to a ripe old age, but I am quite willing to do the job I have been given.

What are your favorite films and books?

It’s been that long, the last movie I saw was Michael Collins. I like the black-and-white version of the Thirty-Nine Steps. I’ve always wanted to go to the Scottish Highlands.

I also like Into the West, Gabriel Byrne’s film. As for books, I liked Richard Llewellyn’s How Green Was My Valley. I like reading [poets] Seamus Heaney, Patrick Kavanagh, and Paul Durcan.

And your favorite place in Ireland? Outside your constituency?

It has to be Donegal. I spent most of my summer holidays there, my mother’s from Donegal and my grandparents had a farm five miles from Buncrana at a place called The Illies.

I recited a poem about Eddie Fullerton (a Sinn Féin councilor, murdered in his Buncrana home by loyalists) on the Late Late Show and it’s about the Cranna River that runs through The Illies.

The next morning I went into the Royal Irish Academy to present prizes to schoolchildren from the North and they had laid out for me a map of the area with the twin bridges.

I go to Gweedore as well and up around Bunbeg. I fish in different places, in the Doochary River in Donegal and also in Mayo, Lough Mask, and in Lough Caragh in Kerry just outside Waterville.

I sometimes feel guilty when I’m standing in a river fishing that I’m not with my family. But I know there are days when I need to do that, in fact, my wife says to me that I should, and she’ll be very forcible and tell me to go fishing!

We walk a lot together. Obviously for security reasons we pick different routes, although I’m not preoccupied by that. It’s the way the world has taken me. Mostly we take the car to Donegal and walk on different beaches.

Recently, we left the house at ten in the morning to walk three miles, and we walked 12 miles to the Donegal border and back along the railway line by the Foyle. It’s brilliant – you can do it without seeing a single car.

Do you have friends with whom you don’t discuss politics?

My wife, my children, my mother.

How have you personally borne up under all the pressure?

(Sigh). I think what drives me on more than anything is being very, very conscious that I am going forward with the hopes of 25,000 Mid-Ulster voters. People place so much hope in their political leaders, to make sure they get equality and justice and peace.

What was your darkest moment? Have you ever despaired?

Bloody Sunday was a dark day, Enniskillen was a dark day, there have been many, many dark days – the killings at Loughgall of IRA volunteers.

Has there ever been a moment when you thought the peace process wasn’t going to work?

I actually believe that we have constructed a process (long pause for thought) which can’t fail. I think that we have done something very powerful on this island over the course of the last ten years. I actually think there are far too many good people in favor of the peace process and the Good Friday Agreement for it to fail.

That doesn’t mean the Good Friday Agreement won’t fail. I know there are powerful forces out there. Before the process, the big battalions in the British media told the world that republicans were the problem. The 1994 cessation forced many people who had heard that message to reevaluate it.

Decommissioning has been a barrier to implementing the Good Friday Agreement. You say David Trimble has willfully misinterpreted that clause in the Agreement. Did he understand what he was signing up to at the time?

Of course he did. The section is very, very clear. The governments spoke to all of the parties individually. Our contribution was reflected in the wording agreed upon. The Ulster Unionists lost the argument. They could not have been under any doubt. If they did, they are very poor negotiators.

Jeffrey Donaldson (Ulster Unionist Party representative) walked away because he realized what that part of the Agreement meant. David Trimble is a constitutional lawyer. Of course he knew what it meant.

Once I knew, within hours of the Agreement being made, that David Trimble had extracted a letter from Tony Blair giving assurances on decommissioning, I knew there was going to be trouble.

What about a South African-style Truth Commission?

The reports from South Africa on that have been particularly mixed, so I think it would need thinking about. We need to be cautious, although in a society where there has been a lot of hurt inflicted, many people do seek the truth.

I certainly think it should be considered. It would need to be approved by all the parties to the conflict, including the unionists and the British government.

What about press and political criticism of you personally? Does it bother you?

I read An Phoblacht, The Derry Journal, The Mid-Ulster Mail, The Irish Times, The Observer, The Irish News, The Derry News and Ireland on Sunday. I don’t read The Daily Telegraph, I wouldn’t know from one day to the other what was in it. I don’t read The Sunday Times. I just work on the basis that they are so opposed to us that every day is a hatchet job, so it doesn’t affect me.

I know someone is writing a book about me at the moment (Liam Clarke, Northern Ireland correspondent of The Sunday Times). That will be a hatchet job. I have had no input into it whatsoever.

I’m told he and his associates have been interviewing people they believe are friends of mine. But I’m satisfied no friend of mine would speak with them.

That sort of thing comes out every week, so it will just be the same stuff in the form of a book. I think that in the world that I live in you have to take a very philosophical and sensible approach.

What is it about your personality that has enabled you to keep calm amidst all the madness of the last 30-40 years? Someone once said you had a soldier’s mentality.

I think that’s a much too simplistic analysis, absolutely. I’m much more political than that. I am just an ordinary person in extraordinary circumstances. I was working in James Doherty’s shop in Derry when the RUC were battering people in the Bogside.

Before the British Army came to Derry I would always have regarded myself as a very quiet, inoffensive person. It’s easy for me to say that, but anyone who knew me then will confirm it. I was the kind of person, if there was a fight, I would get in the middle and try to stop it. (Laughs)

If I could have written the script for the last 30 years, I wouldn’t have written down what we have all been through. I would much rather have lived an ordinary life, I didn’t choose this life.

What started you writing poetry?

Sometimes a thought comes into your head and you try to put it down on paper. I haven’t written that many, maybe a dozen or so. They’re no threat to Seamus Heaney.

Do you ever sit down and write your thoughts into a laptop, like Gerry Adams?

I don’t use a laptop, I don’t know how to, but I am going to learn because I think it would be useful. Mostly if I want to put something down, I write it – I feel more comfortable with that.

Have you managed to be a good father to your children, despite prison, politics and so on? Do you ever feel guilty that you didn’t spend enough time with them?

I do feel guilt, absolutely, but when I’m there I try to be the best father I can be and I have a great relationship with my children and with my wife and grandson. But I think many republicans experience that feeling of guilt – we lead very difficult lives.

Right throughout the second half of the `70 and `80s, you were also bringing up children. How did you manage it?

My wife bore the greatest burden with great difficulty and deprivation – but I tried to do whatever I could. No matter where I was I nearly always managed to get home late at night. My family has always been very important to me but so has the community.

Derry is a community that has been through some terrible events and there’s a closeness about it, and a great understanding there. When you go back to a community like that, it’s like a family with its arms wide open.

Have your children ever blamed you for choosing the republican movement over them?

None of my children have ever said that but it doesn’t mean some of them don’t think that. Children who are part of families who are part of a struggle, when they grow up, can rationalize and make judgements about whether it improved their community and, by extension, themselves. So my children understand the work I participate in and the huge importance of the peace process.

They are not in Sinn Féin or in any way involved politically. They are very normal children. My family has probably seen less of me now, because of the peace process, than they did at the height of the Troubles.

Do you think they’re proud of you?

Only they can answer that. I certainly hope they are. ♦

Note: This interview was published in 2001. Martin McGuinness died on March 21, 2017. He was 66. There is a very good documentary about his life that you can view on TG4 (Ireland’s Irish language station). It’s a mix of Irish language and English spoken but you can watch with captions. If you are new to TG4 you are in for a treat as it has fantastic programming and it’s FREE. You can watch the McGuinness documentary HERE

I was fortunate enough to have been on a first name basis with Martin. He was one of the most outstanding individuals I have ever met. Bar none.