On July 18, 2001, Dorothy Marie and Gwen Hennessey of the Sisters of St. Francis of The Holy Family, left their fellow sisters and friends to report to Pekin Federal Correctional Institute in Illinois. They were sentenced to six months for a November 2000 protest at the School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia.

Founded in 1946 and funded by U.S. taxpayers, SOA trains Latin American soldiers in combat, counter-insurgency, counter-narcotics and commando operations.

Opponents of the school say it trains them in outright murder and inhumanity.

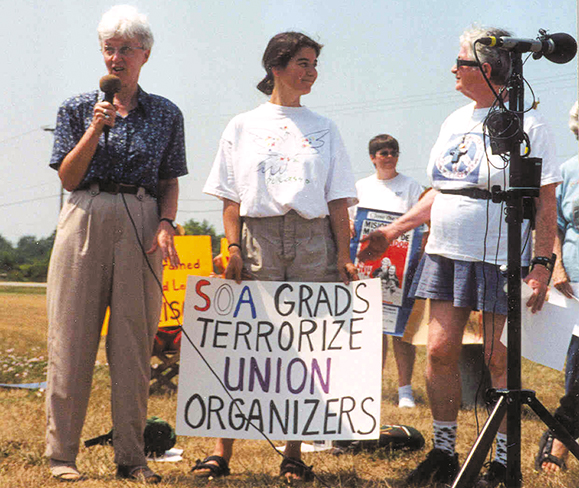

For 11 years, protests, fasts and vigils have taken place in the U.S. and Latin America, calling for the closing of the school, with the combined jail time served by all SOA protestors being 30 years, and the average sentence of six months. Last November, 10,000 gathered at the school’s gate and 3,000 marched in a symbolic funeral procession for the many civilians and missionaries who have been slain as a result of the actions of SOA graduates. Then they crossed the line onto federal property. A total of 26 protestors, 13 men and 13 women, were arrested, tried and convicted. Four were nuns; the Hennessey sisters are two of them.

Sister Dorothy Marie is 88 and Sister Gwen is 68.

Gwen Hennessey.

Dorothy Marie Hennessey.

This was their fourth protest outside the school. Receiving a `ban and bar’ on their first march in 1997 meant the sisters were not to set foot on a United States military reservation again for five years. They were prepared for consequences when they returned to the school for 1998’s march. Nothing happened. Nor did it in 1999. But in 2000 the law caught up with them. Those with previous `ban and bars’ were given jail time and $5,000 in fines.

Sister Dorothy, offered house arrest because of her age, turned it down. “We formed a bond with the 26 other SOA protesters. I am not an invalid,” she stresses, speaking on the phone from Pekin Correctional Institute. “I will serve my time with the others.”

An invalid she certainly isn’t. In 1986 she took part in a walk across America to protest the Cold War. Aged 73 at the time, she found the most inspiring part of the nine-month trek, in which she walked up to 24 miles a day, was the people she met: “I was coming from a sort of cloister to mingle with so many people and so many ideas.”

Sister Gwen is no novice in activism either. Her participation in a sit-in in Senator Charles E. Grassley’s office to protest funding to the Nicaraguan contras landed her in county jail for a few hours in 1987. She ultimately served a sentence of 20 hours community service, something Sister Gwen probably would have gladly done anyway.

The sisters’ infectious good nature – they even joke about the prison food having “too many carbs” – could cut through prison bars, but both turn serious when talking about the SOA.

They point to trials and investigations that conclude that SOA graduates are responsible for some of the most horrific human rights violations in Latin America. Manuel Noriega of Panama might be the most notorious of the 60,000 to pass through its gates but there are many others. The words `kidnapping,’ `torture’ and `gang rape’ run rampant through the rosters of SOA graduates on the SOA Watch website. In Haiti in 1988, armed men broke into a church during mass and opened fire. A total of 12 parishioners died and 77 were wounded before the church was drenched with gasoline and set on fire. The Americas Watch Report states that witnesses identified two participants as deputies of then mayor, Colonel Romain. Romain publicly justified the act. In another atrocity, the United Nations Truth Commission Report concluded that in El Salvador SOA graduates were responsible for the El Mozote massacre of 900 civilians.

The list is long, and the sisters and many more, are convinced that the connection that these men have with the School of the Americas is more than coincidence or a few bad apples.

The school was closed on January 17, but quickly reopened as The Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHISC) as a result of the Defense Authorization Bill for Fiscal 2001. The measure passed when the House of Representatives defeated, by a narrow ten-vote margin, a bipartisan amendment to close the school and conduct a congressional investigation. But opponents aren’t buying the new name. Even SOA supporter the late Georgia Senator, Paul Coverdall, called the changes `cosmetic.’

“Different name, same shame,” Sister Gwen insists. “They might rename it or move it, but we want it closed for good.”

So do others. In May, representatives Jim McGovern, Joe Scarborough, Connie Morella, Christopher Shays, Lane Evans and the late Joe Moakley introduced Bill HR 1810 to close WHISC and establish a joint congressional task force to assess U.S. training of Latin American military.

Meanwhile, protests continue throughout the continent, with another `funeral march’ at Fort Benning scheduled for this November. The sisters say they’ll be wishing they were there.

Gwen, who cares for nuns with Alzheimer’s at the convent, stresses, “I would like to emphasize what a tremendous inconvenience this [being in prison] is. But we have to put it in perspective with the many who have suffered and died in Latin America.”

Dorothy is concerned about the other inmates. “There are women here at camp and their children are growing up without them. One woman is here because her friend was doing drugs and she knew. We need to get rid of the conspiracy drug law. And the 10-year mandated sentence for first-time offenders is unjust.”

The Irish saints had passion, courage, and tenacity; the Hennessey sisters have one thing more: each other.

Their close bond is evident to all with whom they come in contact with, as is the pride they take in their Irish heritage. Their friend, Franciscan Sister Rita Geodken of Dubuque says, “Oh, they love their Irish heritage. They are intensely proud of being Irish and Catholic.”

The sisters, whose great-great-great-grandparents on their father’s side, were natives of Co. Cork, grew up on a farm in Iowa.

In Sister Dorothy, the desire to enter the religious life came while she was still a teenager: “I was the oldest of 15. No one had ever done anything like this, but I knew somehow…I was not pushed, but tempted. Finally I accepted.”

“It was the pastor’s fault,” she says as to why she chose the Franciscans: “he had cousins in that order.” Maybe God had more of a reason. Sister Rita points out that their Franciscan community’s main focus is issues of justice and that “the spirit of God is leading them to live a life of justice.”

The spirit runs deep in the Hennessey family.

Another sibling, Miriam, also a Franciscan sister, was killed by a car in 1990, as she crossed the street to work at a homeless shelter in Davenport, Iowa.

The example of her older siblings influenced Gwen to enter the religious life, and it was through their brother, Ron, a Mary Knoll priest serving in Guatemala in the 1960s, that the sisters first heard of the brutality in Latin America. A friend of assassinated Archbishop Romero, Father Ron was in the church when San Salvadoran military fired on mourners at Romero’s funeral. Those responsible were SOA graduates.

When they ask why, with so many reasons for closing the school, the government still wants it open, the sisters say they always receive the same answers: that it is necessary to train these military men if the U.S. hopes to win the war on drugs.

But according to SOA Watch and Witness for Peace delegates who traveled to Putumayo, Colombia, the U.S.-funded aerial spraying known as fumigation is devastating the Colombian people. Their food and air poisoned, side effects range from skin rash epidemics to birth defects. It is only part of the $1.3 billion U.S. military aid package to combat drugs in Colombia. Ten thousand Colombian soldiers, those using these funds, were trained at SOA.

Sister Gwen’s opinion is that the U.S. government “needs to focus on the kingpins in this country who want the drugs, not the farmers. They need to stop destroying their land and crops in an attempt to destroy drugs. They’re starving the people.”

The War on Drugs has been long and debate over it heated. As the pressure continues to rise on those involved, no one answer has led to a solution. Drugs continue to permeate the U.S. and make their way into the hands of new and younger users.

But the Hennessey sisters, the rest of the SOA 26, and the thousands who protest believe there are more effective, more just, more humane methods than those being taught by the School of the Americas.

When they are released on January 14, Dorothy and Gwen look forward to continuing their vocation in justice and compassion for as long as they are able.

They surely have enough spark to carry on through more than a few fiery years. ♦

Leave a Reply