By the time Judy Garland made her first and only concert appearance in Dublin in July 1951, she had been an international star for more than a decade. She had starred in 27 feature length films, performed on more than 200 radio shows, appeared in hundreds of national and international magazines and newspapers, and recorded more than 70 records and albums. The diminutive songstress, whose voice could pack an emotional wallop equal in intensity to a cosmic collision, arrived in Ireland, land of her ancestors, after a six-week sold-out run at the London Palladium.

At age 29, Judy had already been performing for 27 years. Her debut had taken place on the stage of her parents’ Minnesota moviehouse where she and her two older sisters, Mary Jane and Dorothy Virginia, performed in simple song and dance at Friday evening amateur shows. The girls’ parents, Frank Gumm and Ethel Milne, had been a small-time vaudeville duo under the name of “Jack and Virginia Lee, Sweet Southern Singers.” The couple had been performing together for only a short time after their January 1914 marriage when they discovered that they were going to be parents. With a family to support, Frank Gumm decided to forgo his dream of a career in entertainment in favor of the more practical and bought a moviehouse in Grand Rapids, Minnesota.

“My father had a lovely Irish tenor voice,” Judy liked to say, recalling his soft rendition of “Danny Boy” sung to her and her sisters as a bedtime ritual.

The first members of Gumm’s maternal line, the Baugh family, arrived from Ireland in the early 1700s and settled first in Virginia where they ran a successful commission mercantile. Both the business and the family expanded into Kentucky and then Tennessee, where Elizabeth Clementine Baugh met and married William Tecumseh Gumm in the town of Murfreesboro in Rutherford County. After the marriage, William was employed by his wife’s family to manage their business affairs in Tennessee.

Well-educated, polished, staunch Episcopalians, the Gumms enjoyed a well-appointed Southern life. Of William and Elizabeth Gumm’s four sons and one daughter, it was third son Frank who attracted the most attention. While the Gumms were not known as entertainers, Frank was remembered for his rich voice and eagerness to perform. A good student who considered the priesthood for a short time while attending the University of the South in Sewanee, he took part in all of the school’s productions and eventually took his act on the road, eager to carve himself a place in vaudeville.

Frank headed north to the Great Lakes area where he started out as a singer – a popular one – in several small theater houses in Superior, Wisconsin. In 1913, he obtained a position at a large Superior theater. Frank did very well there and he enjoyed his work, especially since it gave him the opportunity to get to know the young female pianist assigned to accompany his performances.

At age 20, Ethel Marion Milne was not only a talented pianist, but a hard-working, intelligent woman unafraid to tackle and break down the conventions that limited women of her day. Ethel was the eldest child of the Irish Evelyn Fitzpatrick and the Scot John Milne. In keeping with the family’s heritage, and in direct contrast to the more staid Gumm family, the Milnes and the Fitzpatricks had been regaling family and friends in America with song, dance and story since 1727.

Judy Garland related how she and her sisters often danced reels and flings with their grandfather while grandmother sang. “I’m Scots-Irish, you know, and my grandparents’ house was filled with the music from the countries,” she told reporters on her Irish trip.

The Milnes originated in Aberdeen, Scotland, moved first to Ireland, then crossed the ocean, settling in Ontario, Canada during the mid 1800s. The family of six children and several other extended relations lived in Canada for several years before emigrating to North America.

The Fitzpatricks emigrated from Ireland to historic Tryon County, New York in 1766. They aided the British during the American Revolution, and, like most other Loyalists in the upper New York area, they moved at the close of the war across the St. Lawrence River to Ontario, Canada.

Hugh Fitzpatrick Jr., Garland’s maternal great-grandfather, one of 18 children, was sent from Canada to Ireland to learn the shoemaker trade. It was there, in 1858, that he met and married Mary Elizabeth Harriot, an orphan raised in a Dublin convent. Soon after their marriage, the couple sailed for Canada and their first child was born there. The couple had a total of ten children, all of whom were baptized in Ontario’s Trinity Episcopal Church, of which the Fitzpatricks were founding members.

During the late 1800s, the railroad was barreling across North America and up into Canada with more and more track being laid every day. Hugh Fitzpatrick sold his property to the expanding Grand Trunk Railroad Company, then packed up his family and moved to the United States, settling in Michigan. The Milne family also moved from Canada to Michigan, where Charles Milne worked for the Great Western Railroad. After meeting in the community, the Milne and Fitzpatrick children, John and Eva, married.

Music was equally as important as education for the Milne/Fitzpatrick family. All played instruments and sang, and the family offered amateur shows within the community and surrounding area. Son Fred Milne recalled, “When we got together, it would be in no time at all that everyone was performing. Songs, dance, storytelling, little skits. The Milnes would perform at the drop of a hat.” Eldest Milne son, John, Jr. would later host his own local radio show under the name “Little Jack McCormack,” during which he would offer audiences traditional Irish melodies and storytelling.

Such was the family tradition into which Judy Garland was born on June 10, 1922. Beginning life as Frances Ethel Gumm, Judy was named for both her parents, who had been anticipating the birth of a boy. Said Judy as an adult, “My parents were hoping for a boy and kept referring to me as Frank, Jr., but I don’t think they were too disappointed with another girl.” Although christened Frances, Judy was always called “Baby,” even in school and by her friends.

Baby’s first four years were spent in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, where she and her sisters performed occasionally at local community events and clubs, as well as at their parents’ theater. The Gumm family was active in community affairs and they were prominent members of The Church of the Holy Communion/St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, where Frank served as choirmaster and Ethel played the organ. Judy recalled, “I loved church music” and “I first started singing in our church choir when I was a little girl.”

In June 1926, the Gumms and their three daughters set out on an extended summer vacation to Los Angeles, California. The family took a roundabout route west by train, stopping in several towns along the way to perform. Frank and Ethel did a revival of their “Jack and Virginia Lee, Sweet Southern Singers” routine and the girls did simple song and dance featuring Baby’s toddler acrobatics. Once in California, the Gumms were so taken with the area’s balmy weather, healthy lifestyle and good economic conditions that the decision was made to relocate permanently to Los Angeles.

Baby and her sisters continued to appear in a variety of amateur and semiprofessional shows in and around the Los Angeles and Hollywood areas, including performances for a local Jewish organization where Baby was asked to sing a traditional Hebrew piece. “How cute,” Grandmother Fitzpatrick remarked “A little Irish girl singing a Jewish song.”

Ethel Gumm was a devoted wife and mother who put her family first. Although she would later be characterized as exploitative and negligent, fact-based details, including those supplied by her daughters, describe Ethel as a loving, kind and open mother, often criticized for being too indulgent. Contrary to what many have said, Ethel did not push her daughters into performing, and there were several long stretches of time when schoolwork or friends took precedence. Said Judy’s older sister Virginia, nicknamed Jimmie, “We lived a terribly normal existence. There was none of that `born in a trunk’ bit. We were one very happy family.”

Both Frank and Ethel Gumm were a popular and well-respected couple who instilled in their children a deep love and desire for music and entertaining.

It was after a summer 1935 engagement at the Cal Neva Lodge (so called because of its location on the border between California and Nevada) that the youngest Gumm daughter, now known as Judy Garland, having taken her new first name from her favorite song of the day by Hoagy Carmichael and her last being given to the sisters by the M.C. at one of their engagements, attracted the attention of a Hollywood agent who promptly made arrangements for her to audition at all the major studios.

“The agent towed me all over, from one studio to the next. They all said the same thing. Get her away from here. There’s nothing I can do with her. You see, I was, to the studios, no age. I wasn’t a child wonder, nor was I an ingénue or a grown up. A teenager was regarded as a menace to the industry and fit only to be stuffed in a barrel until she could be made into a glamour job. They simply didn’t know what to do with me.”

With a little luck and a whole lot of persistence on the part of her agent, Judy was soon auditioned by the MGM studios and Louis B. Mayer, who quickly signed the 13-year-old to a standard seven-year contract. Just weeks after signing with the studio, Frank Gumm passed away suddenly, a victim of spinal meningitis. Judy recalled her father’s death as “the worst event of my life.”

Like the other studios, MGM wasn’t quite sure what to do with young Judy and instead of immediately casting her in films, they started her on the slow track to stardom by having her entertain at studio parties and benefits as well as on radio. Judy’s big break came at a birthday party for the then king of motion pictures, Clark Gable, when she was enlisted to sing a specially prepared version of “You Made Me Love You” in which Judy, representing all the young girls in America so in love with Hollywood’s number one star, sang of her love and devotion to him in the form of a fan letter.

The reworked song became known as “Dear Mr. Gable” and catapulted Judy to the forefront of the attention of MGM’s executive group. Within days a special part for her was written into the studio’s next big production, Broadway Melody. Soon after, Judy began making films regularly and by the summer of 1939, as she received rave reviews for her performance as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, she had completed seven MGM films, including two with co-star Mickey Rooney, and made several recordings for Decca records.

In 1939, Judy Garland was receiving more fan mail than any other star on the MGM lot, as well as much praise and respect from her fellow actors. Veteran actress and leading lady (and also of Irish ancestry) Mary Astor portrayed Judy’s screen mother in two films and expressed fondness for the young actress. “Working with Judy was sheer joy. She was young and vital and got the giggles regularly. There was no use going on with a scene until she got it out of her system.”

Judy’s co-stars from The Wizard of Oz were also quick to commend the young actress. “Everybody on the set loved her,” said Margaret Hamilton, who played the Wicked Witch. “She was just a darling and sweet person. She was a true 16-year-old. Not like some 16-year-olds who act as if they were 60!” Added Jack Haley who portrayed The Tin Man, “Judy was such a doll, a lovely person. You hear stories about her, but I never saw any of that. She was a lovely, happy young girl with impeccable manners. She was a wonderful person and it was a great pleasure working with her.” Ray Bolger who played The Scarecrow agreed, “I had great admiration for Judy both as a person and a performer. Judy had a magic quality, a special presence. She liked to have fun, but once the cameras were rolling she was serious and dedicated. You’ll read stories about how difficult Judy became to work with, but I never saw any evidence of that and I made two pictures with her. She was always so respectful of her fellow performers and the technicians. We never had any problems with her.”

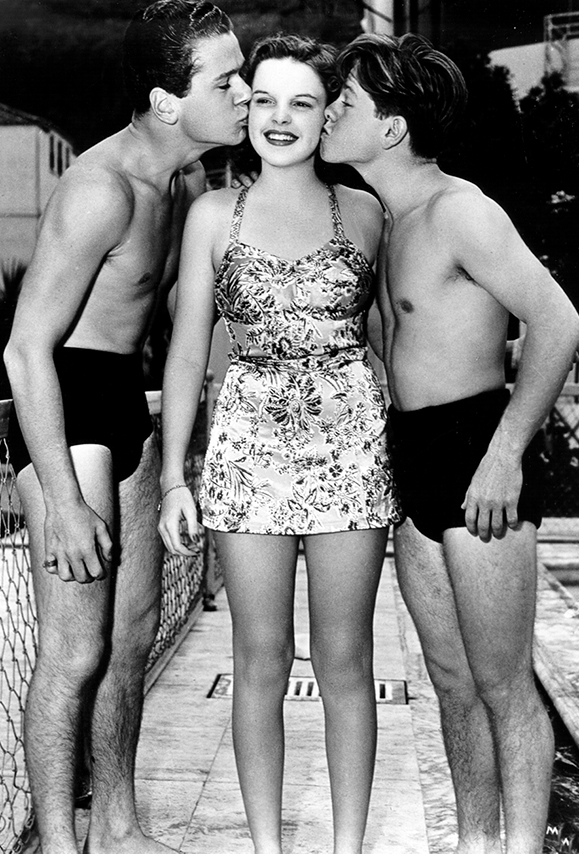

Soon after The Wizard of Oz was released, MGM starred Judy and pal (and fellow Scots-Irishman) Mickey Rooney in Babes in Arms, the studio’s biggest budgeted movie for 1939. The premiere of Babes in Arms on October 10, 1939 also marked the occasion of Judy’s hand and foot-printing at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. The following February 29, 1940, Judy was awarded a special Academy Award for her work in The Wizard of Oz.

At the Academy Award ceremony, Judy sang “Over the Rainbow” which was named Best Original Song. Judy was now the number ten overall box office draw in the nation and the number three female draw as determined by The Motion Picture Exhibitors’ Alliance. These achievements represented a definite affirmation of success, if not of world fame and recognition, for any star, and Judy now enjoyed the status of being one of MGM’s most important stars.

Over the decades stories have depicted Judy as being ruled over by a despotic studio machine that dictated her every move, starved her in order to keep her thin, then fed her amphetamines to keep her working and sleeping pills to gain forced rest. This description appears to be false. Though described as an exploitative stage mother, Ethel Gumm was in fact a formidable force who refused to allow Louis B. Mayer to dictate how she and her family would live their lives. Said Judy’s sister Jimmie, “It was never a case of Mama saying of the studio executives, `You do whatever they say.’ If Judy complained, then Mama went right up and complained.” MGM executives would later recall numerous letters and memos from Ethel, all in an effort to make sure that Judy was content and not overburdened.

Although Judy’s teenage years as an MGM star comprised of much hard work and a busy schedule, they were also marked by just as much of, if not a bit more than, the usual amount of teenage fun. As an adult, Judy herself would say of MGM, “They made us what we are. There were lots of good times, too.”

But at the same time, Judy was growing increasingly disappointed with her film roles. Soon after her 18th birthday in June 1940, she began to bristle at always being portrayed as a “little girl.” MGM was seemingly bent on keeping her in a sort of perpetual adolescence and Judy yearned for roles that were at least a little more mature. MGM obliged by casting her in Little Nellie Kelly, the film version of the 1922 stage hit by George M. Cohan, in which she would get to play, at least for a short time, an adult married woman.

Little Nellie Kelly cast Judy not only in her first adult role, but also in her first love scene. The sentimental story involved a young Irish woman, Nellie, who falls in love with and marries an Irishman, Jerry Kelly, who is not to her father’s liking. The trio emigrates to America where Jerry, played by George Murphy, works his way up the ranks of the New York City police department and Nellie becomes pregnant, but dies in childbirth. The child, a little girl named Nellie, is also played by Judy, and the remainder of the story concerns Little Nellie’s efforts to bring her father and her grandfather together while experiencing her own first love with a man, portrayed by Douglas McPhail.

Brimming with traditional Irish warmth and charm, Little Nellie Kelly featured some of Judy’s best-loved songs, several of which remained staples of her later concert career. Judy recorded “Danny Boy,” “A Pretty Girl Milking Her Cow,” “Nellie Is a Darlin’,” “Singin’ in the Rain,” “Nellie Kelly, I Love You.” Little Nellie Kelly may best be remembered, however, for the introduction of Roger Edens’ composition “It’s a Great Day for the Irish”, written especially for Judy, which would go on to become one of the most popular of all Irish anthems.

Also included in the film is a recreation of Irish immigrants arriving in New York City by ship, passing through Ellis Island and later being sworn in as American citizens. There is also a depiction of the New York City Police Academy and its training program, and a reenactment of the city’s world-famous St. Patrick’s Day Parade and the New York City Police Department Emerald Society’s yearly grand ball.

While the film did not receive a tremendous ovation, Judy drew critical acclaim for her successful transition from child to at least somewhat of an adult role. As the adult Nellie Kelly, Judy appeared in her only death scene, which critics said she carried out with “sensitive skill” and was able to “convey two totally different and believable characterizations.” The scene was so movingly portrayed that the film crew was not allowed on the set during filming so as not to have their sniffles and sobs picked up on the soundtrack. “Nellie” also gave Judy the opportunity to act in her first “real” love scene, although she often joked that, due to co-star (and future U.S. Senator) George Murphy’s much older age, “I kept teasing that I felt like his Tennessee child bride.”

Along with more mature roles came more mature feelings, and in July 1941 Judy entered into a classic “too young” marriage to David Rose, a musician 12 years her senior. Judy in later years said “I don’t know how to explain that first marriage; there wasn’t any real reason for it. I was much too young, but you couldn’t have made me believe that then. Mom tried to tell me; so did everyone else. I thought my superficial knowledge of the world was all there was to know.”

The Garland-Rose marriage lasted just seven months, although the formal divorce would not be finalized until 1945. After her separation from Rose, Judy entered into the busiest period of her career up to that point, filming several big pictures including For Me and My Gal, Girl Crazy and Presenting Lily Mars, while taking part in countless radio shows and making personal appearances. Judy was also the first female celebrity to donate time and talent towards the growing war effort, long before there were any USO, Victory or other organized programs. Although she had always expressed a strong desire to go overseas, Judy’s wartime effort would be limited to the home front, offering more of her time to Uncle Sam than nearly any other star in Hollywood. “They tell me I’m doing my bit, making movies, visiting camps and singing on government radio shows – but I’d like to do more.” And more she did! Judy appeared, sometimes almost nightly, at the Hollywood Canteen, a local social club for servicemen, as well as took part in several cross-country war bond drives and rallies. Judy also visited numerous training camps and military hospitals. This all in addition to her regular work schedule.

The effect of all these projects became evident as Judy dropped weight and started experiencing problems sleeping. In later years, Judy would note this period as the true beginning of her erratic sleep patterns, which necessitated her use of prescription sleeping pills to gain rest, then prescription amphetamines to counteract the sedatives’ effects and to help maintain her figure, which was always a bit on the full side.

“Diets were not for me,” she would explain, “so I stuck to the pills without really knowing their effect on me.” Although she did manage at times not to rely on any type of medication, all of which had been prescribed by doctors, this pattern of pill taking would grow steadily.

It was at this same time that production began on Meet Me in St. Louis, a work destined to change her very existence. Scheduled to direct Meet Me in St. Louis was Vincente Minnelli, an MGM newcomer from the New York stage. Although not immediately taken with each other, by the time Meet Me in St. Louis was completed in April of 1944, Judy and Vincente had fallen in love. Said Judy to reporters, “Vincente is wonderful. He’s the most interesting man I’ve ever known. He knows everything in the world, honestly, it amazes me – he’s read everything and heard every piece of music and been everywhere, but you’d never think it just to meet him, he’s so quiet and rather shy and always making you laugh.”

During that fall of 1944, Judy and Vincente made another film together, The Clock, which was Judy’s only non-singing film role for MGM. The following June in 1945, the couple was married in a ceremony held in the backyard of the home Judy shared with her mother and sisters. A few months later, Judy and Vincente discovered that they were to be parents, and in March 1946, Liza May Minnelli was born.

While motherhood was a welcome joy for her, Judy’s physical and emotional health began to suffer. She lost weight, could not sleep and began to experience panic attacks and loss of self-confidence. For the first time, her work began to suffer, and she sought help on two separate occasions at health facilities in California and Massachusetts.

No longer wishing to continue with the hectic pace and stressful conditions associated with the making of musical films, Judy asked for and received her release from her MGM contract, and in September 1950 Judy Garland and the MGM Studios ended their relationship.

No longer a film or recording star, Judy began to consider her options. She was appearing fairly regularly on pal Bing Crosby’s radio program when she received an offer to appear in concert at the London Palladium. After much consideration, she accepted the invitation and left for Europe by boat on March 30, 1951. At this same time, Judy officially filed divorce papers with Vincente Minnelli and the two parted good friends, still caring much for each other and both completely devoted to their daughter.

Judy’s arrival in London was nothing short of spectacular. Ships in the harbor flashed signals spelling out her name, and there were long horn blasts from each ship just for her. Opening night at the Palladium was stupendous and the entire four-week engagement was sold out soon after the box office opened. Although it was unplanned, Judy extended her concert tour to Ireland and Scotland, lands of her grandparents and great-grandparents. She was happy to be “home.”

In Scotland, when Judy learned that many of the local children were hoping to see “Dorothy,” but lacked the money to pay for tickets, she herself purchased the tickets for them, filling a whole section of the theater with children during one afternoon performance.

Judy’s first Scottish appearance was on May 21 at the Glasgow Empire where she appeared to a “multitude of fans” and was described as “strenuously engaging.” This was followed by a May 29 performance at the Empire in Edinburgh where she was “welcomed with a storm of applause.” Dubbed a “bonny wee lass with a well turned leg,” Judy related stories of her childhood influenced by her “Scots-Irish grandparents” to the audience of more than 4,000, even mentioning the gift of her “fine complexion,” which she said was a gift from her Irish grandmother.

During the Edinburgh performance Judy invited several children in the audience up on stage to join her for an impromptu fling, then “shook the walls of the theatre with her raucous version of `It’s a Great Day for the Irish,’ explaining to the audience that it was a song written just for her for her film, Little Nellie Kelly. Judy also offered “Loch Lomond,” accompanied by a lone bagpiper, and included “Flower of Scotland.” Said the press, “The audience adored her and would have carried her on their shoulders out of the theatre and down the Royal Mile if she had allowed it.”

From Edinburgh Judy returned to London, then went to Dublin for her July 2 concert at the Theatre Royal. While in Dublin, Judy leaned over the windowsill of her room one evening and serenaded a throng of people who had gathered below trying to get a glimpse of her. She gave a press conference at which she welcomed all questions, joked with the audience and even stopped to “have a chat with the girls” who worked at the Metropole. For her Theatre Royal appearance Judy sang the Gaelic version of “A Pretty Girl Milking Her Cow” – “Cailin Deas Cruidte na mBo.”

Although Judy never returned to Ireland or Scotland after 1951, this marked the start of the persona of “Judy Garland in Concert,” as she now turned to concert tours, often one after another.

After filming A Star is Born, Judy toured throughout the 1950s, including two never equaled performances at New York City’s Palace Theatre.

In 1952 Judy entered into her third marriage, with Sid Luft, who also became her manager. Judy and Luft had two children, Lorna and Joseph. From the time they were very young, Judy tried to take her kids with her everywhere, even if it meant hiring tutors or enrolling them in school in various cities while she performed on concert tours or completed films. Though she has been accused of being a poor mother, both Liza Minnelli and Lorna Luft have stated on numerous occasions that Judy “was a fabulous mother.”

In all Judy completed more than 1,100 live appearances. An appearance at Carnegie Hall in April 1961 is still hailed today as one of the all-time great live music events. In addition to winning five Grammy Awards, Judy at Carnegie Hall on Capitol records has never been out of print. Her concert appearances continued well into the 1960s including one where the press said, “Judy still struts her Irish proudly.”

Of Judy’s three children it is her two daughters who have demonstrated that same affinity and predilection for performing that first made itself known in their Celtic ancestors of long ago. In addition to their numerous achievements in American entertainment, Liza Minnelli and Lorna Luft have both appeared several times in concert in Ireland and Britain. And in 1996, Lorna starred in the Irish premiere of Follies at the National Concert Hall in Dublin alongside Ireland’s top male musical star, Enda Markey. She also took her dazzling and critically acclaimed show Hollywood and Broadway – The Musicals to Belfast’s state-of-the-art Waterfront Hall in 1997.

Judy’s daughters have tried hard to make people understand that despite many daunting challenges and sad circumstances that seemed to follow her, especially during the later years of her life leading up to her death in 1969, their mother was a profoundly loving, funny, warm, kind person, who led a life that she herself termed “very happy.”

And like her ancestor, the Dublin-born orphan named Mary Harriott Fitzpatrick, who courageously left the only life she had ever known to build a family and future in an unknown land, Judy never lost her Celtic soul. ♦

Leave a Reply