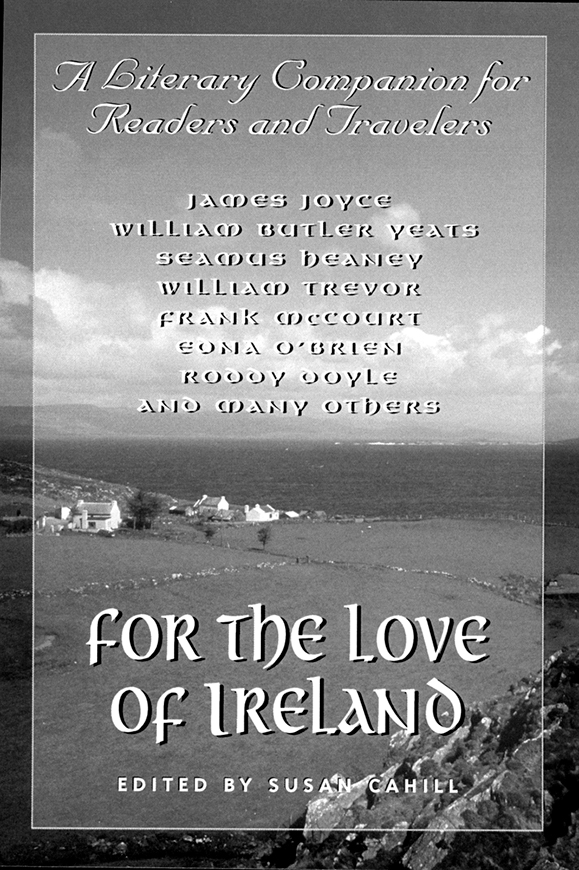

Author Susan Cahill tells what prompted her to write For the Love of Ireland: A Literary Companion for Readers and Travelers.

I grew up in New York City in an Irish-American family whose patriarch on my mother’s side fought to keep Ulysses out of the Queensborough public libraries and later grand-marshaled the St. Patrick’s Day Parade.

As a graduate student in David Greene’s course in Modern Irish Literature at New York University, I listened to Professor Greene read aloud from Ulysses through the 15 weeks of one spring semester during the war in Vietnam. I liked best the Cyclops episode (it’s in my book), the parts spoken by Joyce’s un-heroic hero, Leopold Bloom, the wandering Jew of North Dublin. In my imagination, he was from Queens and he rode the Flushing / Times Square IRT.

Greene read with pleasure, annotating a bit here and there, about Joyce’s Dublin and what we’d find left of it if we made the pilgrimage. He mentioned Sandy-mount Strand, Davy Byrne’s moral pub, the hill of Howth where Molly Bloom said her Yeses and the two hundred potential pilgrims in the lecture hall could feel his affection for the place.

To me Ireland was Joyce and Joyce was Dublin. And at the tail-end of our late ’60s honeymoon that my husband Tom and I spent mostly in Italy, we tried to get a flight into Dublin. But our plane landed in Cork, and for three days of howling freezing rain, we found ourselves driving not east back to Dublin, but southwest and then up the west coast. We’d seen the Apennines and the Amalfi Coast in Italy, and climbed the Lorelei Rock above the Rhine in Germany, but nothing prepared us for the Beara over the Healey Pass, the Macgillycuddy Reeks on the Iveragh, the Conor Pass on Dingle, which Paul Theroux calls scarier than the Khyber Pass.

The fog rolled in, out, and over, like waves from the sea; rainbows arced out of nowhere.

The man that I married has a thrilling singing voice and he accompanied nature’s wildness with such authentic Irish songs as “Whiskey in the Jar” and “The Holy Ground,” taking his hands off the wheel to clap to the refrain “Fine girl you are!” I was a long way from my Irish-American St. Patrick’s Days of “You’re Irish and you’re beautiful and you’re beautiful `cause you’re Irish.”

At twilight on the fourth day, as we descended into Quin in County Clare, a rainbow was covering the village.

We made friends with the couple who ran the B&B beside the Abbey, the best-preserved Franciscan foundation in the country, and we have been back to visit many times since. Once, having had the security of a contract from Scribner’s to write our Literary Guide to Ireland, we stayed for a year. The husband became our second child’s godfather; the wife my friend, and, in 1999, my guide through parts of Clare and Limerick, reciting Brian Merriman’s Midnight Court in Irish as we trailed through his and Biddy Early’s neighborhood, doing research For the Love of Ireland, which I chose as the title for my book because it expresses the state of affection which I hope to bring my readers.

The main characters are Irish writers, the Irish landscape, and the connections that both my husband, Tom and I have made with them over the course of 30 years. Having walked, climbed, driven, gotten lost, and lived in Ireland, I’ve discovered for myself how closely the writers’ descriptions match the places travelers can still find today.

Again and again Irish writers find beauty in the name of a place – Inishowen for the Anglo-Irish novelist Joyce Cary, Sligo for Yeats, Ballyferriter on Dingle for the playwright John Millington Synge, Labysheedy for poet Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill. In a country so roiling with contradictions, the attempt to say anything definite about its cultural contexts is as challenging as, say, finding William Trevor’s Nire Valley under a hailstorm in June throughout which the sun still shines and the road signs get blown in the wrong direction. (“Now why would you say `wrong,’ Missus?”)

Knowing Ireland’s multiple identities, the writers represent a full range of them. In a wide range of moods, swinging from delight to cool-eyed criticism to rejection, these visionaries and incomparable wits alert you to any foolish generalizations: they also express their often-comic acceptance of Ireland’s instabilities. Their poems, short stories, and memoirs resound with multiple sensibilities, ancient and modern, fierce and gentle, a pagan and Christian mix – the ground, I think, of Ireland’s seductiveness.

People who take this book on the road will, I hope, appreciate that the selections highlight Ireland’s most dramatic settings – the Dingle Peninsula, the Cliffs of Moher, the North Antrim Coast (or Giant’s Causeway), Connemara. But the plain places are here, too, thanks to the extraordinary writers who’ve found gold amidst the ordinariness – Frank McCourt and Kate O’Brien’s Limerick, novelist Brian Moore’s and poet Maeve McGuckian’s Belfast. Where would Swift, O’Casey, Joyce, and Beckett have been without “dear dirty Dublin”? Some hidden places – the Blackwater Valley, southwest Mayo – are personal favorites (the former loved as well by Elizabeth Bowen and Dervla Murphy, the latter by Grace O’Malley, the rebel Pirate Queen, and Michael Longley). I put red flags of warning on some destinations that are glutted with coaches and tourists in high season. For the most part, though, overcrowding (except around the cities) is not yet an Irish problem. The Anglo-Welsh travel writer Jan Morris loves Ireland especially because it has preserved its pastoral society, which, she says, has been destroyed almost everywhere else in Europe.

In 1999, I found the most absolute solitude in Yeats’s Glencar in Sligo, around Heaney’s Bellaghy in Derry, Slemish mountain in Antrim where St. Patrick the slave boy tended pigs, the Fanad peninsula in Donegal, and in the loneliest place in Ireland, northwest Mayo where Synge set The Playboy of the Western World. Not a cell phone in earshot or an SUV to force your compact into a ditch.

To attempt to name a unifying theme among the writers is to risk exhaustion or absurdity or both. As critics have observed of Samuel Beckett, there is, in centuries of Irish poetry and prose, a counterbalancing of the comic and pathetic, the yes and the no, hope, and despair. (“Almost always,” Yeats believed, “truth and lies are mixed together.”) Representing Ireland’s high tolerance for ambiguity, Irish writers, male and female, allow neither the comedy nor the tragedy of life, neither optimism nor pessimism to become absolute. Until recently, the harsh fact of Irish poverty, with all its consequent suffering and failure, showed itself in every county, in all four provinces. Yet always the writers, taking a cue from their magical landscape (where rain and sun pour forth simultaneously), perform a kind of magic on their unpromising material: they transform the bitter facts by the power of their poetry. In the plays of Sean O’Casey, Brian Friel, and Sebastian Barry, this pattern of redemption by language might pass as a unifying theme. Clearly, it passes the test of longevity. From the beginning, literature, above all other arts, has flourished here. ♦

Susan Cahill, Ph.D., is the editor of many highly praised anthologies, including Desiring Italy, For the Love of Ireland, Wise Women, The QPB Anthology of Writing by Women, and Women and Fiction.

Leave a Reply