“When anything absurd, forlorn, or desperate was to be attempted, the Irish Brigade was called upon.” – George Alfred Townsend

“Oh, God, what a pity! Here come Meagher’s fellows” was the cry in the Confederate ranks. Nevertheless, the Rebels kept up the relentless fire. Captain John Donovan, in the 69th New York, called the combined cannon and rifle fire “murderous” as gaps opened in his unit’s ranks. Still, the Brigade pressed on, men dropping in twos, threes, and in larger groups.

A strange sound was heard above the screams of the wounded and the exploding artillery shells. The Rebels were cheering the bravery of the Brigade. General George Pickett, best known for his charge at Gettysburg, wrote after the battle to his fiancee, “Your soldier’s heart almost stood still as he watched those sons of Erin fearlessly rush to their death. The brilliant assault on [Marye]’s Heights of their Irish Brigade was beyond description. Why, my darling, we forgot they were fighting us, and cheer after cheer at their fearlessness went up all along our lines.”

[Patrick Kelly]’s men swept rapidly through the waist-high wheat in two ranks, with their green regimental flags flying and their weapons at “right shoulder shift.” Lieutenant Colonel Elbert Bland of the 7th South Carolina remarked, “Is that not a magnificent sight?” to his commanding officer as he watched the Irish Brigade closing on his position.

No brigade in the Civil War was more distinguished by its ethnic character than the colorful, hard-fighting Irish Brigade.

Repeatedly hurled into the hottest part of the fighting, these units, consisting mainly of Irish immigrants and Irish Americans, played key roles during some of the most decisive battles of the war.

Originally the Irish Brigade consisted of three regiments from New York City, the 63rd, 69th, and 88th New York. Later, the 116th Pennsylvania from Philadelphia and the 28th Massachusetts from Boston joined.

They were united under the command of Thomas Francis Meagher, who had been sentenced to death for his part in the failed Young Irelanders Rising of 1848. His sentence was reduced to exile, Meagher was transported to Tasmania where he was able to arrange for his escape to America in 1852.

At the start of the Civil War Meagher raised a company of infantrymen and joined the 69th New York State Militia at Bull Run Creek in Northern Virginia.

This first major battle of the Civil War, in the summer of 1861, was an abysmal defeat for the Union troops. The 69th acquitted themselves well but sustained very heavy losses, and when their leader, Colonel Corcoran, was captured, the unit was mustered out of service. However, many of its members later joined the 69th New York Volunteer Infantry and helped form the foundation of the Irish Brigade.

Like Meagher, many of the officers and soldiers of the Brigade were followers of the Fenian, Movement, whose goal was to liberate Ireland from the shackles of the British colonists.

Sadly, many of the battles in the Civil War pitted them against their fellow Irishmen who had immigrated to the South and were soldiers in the Confederate Army.

One of the stories in the book The History of the Irish Brigade goes as follows:

At Malvern Hill, Virginia, the Brigade covered the army’s withdrawal after the slaughter. However, the company commander of the Confederates directed the firing of his men with such daring that the Brigade was pinned down.

Sergeant Driscoll, one of the best shots in the Brigade, raised his rifle and took aim. The rebel officer fell and the Confederates broke away.

“Driscoll, see if that officer is dead – he was a brave fellow,” said the Irish captain.

Sergeant Driscoll complied, but as he turned the officer over he saw that it was his own son who had moved to the South before the war.

Ordered to charge a few minutes later, Driscoll rushed on in frantic grief, calling on his men to follow. He was shot down a few minutes later. His men buried father and son in one grave, set up a rough cross, and went on with the fighting.

The Irish Brigade’s reputation for hard fighting became legend during 1862 as they took part in the bloodbath of the Seven Days, and at Fair Oaks, Gaines’ Mill, Savage Station, and the above-mentioned Malvern Hill, where a Confederate general was heard to remark “Here comes that damned green flag again.”

The Brigade suffered heavy losses at each encounter and there was more to come. The Battle of Antietam, also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg, was the bloodiest single day in American history. During twelve hours on September 17, 1862, some 26,050 Americans fell on the fields of battle. In the very center of this storm stood the men of the Irish Brigade.

Antietam Creek runs north to south and into the Potomac River just north of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. On that afternoon it marked the point at which Confederate General Robert E. Lee planned to invade the Union. As he pulled his scattered army together, the Union Army of the Potomac attacked at dawn at the northern end of the battlefield.

By late morning the combatants on that end of the field lay exhausted or dead and the fighting shifted to the center. Finally, towards the end of the day, the battle shifted to the south. It was against the center of Lee’s lines that Colonel Meagher led the original three regiments of the Irish Brigade at a little after 10:30 in the morning.

The Irish Brigade marched steadily forward behind their three fluttering green silk banners, distinguished by gold Irish harps and the fighting mottos of “Faugh A Ballagh” translated as Clear the Way, and “Who Never Retreat from the Clash of Spears.”

Equipped solely with smoothbore muskets at a time when most of the rest of both armies had rifles (which allow for longer-range fire) Meagher’s plan was to close in and then blast away at a range at which even the smoothbores could not miss.

Their approach carded them up a long slow rise towards a crest in the middle of a farmer’s field. As the Irish crested the ridge they were met with a fierce blast of musketry. The shattering fire came from a line of Confederate infantry partially protected in a slightly sunken road just beyond the crest of the rise. Rather than fall back or retreat, the Irish stood their ground and traded shot after shot at point-blank range with the Alabamans to their front.

Accounts from survivors talk of the battle rage that came upon some men to the degree that when they ran out of bullets they began throwing rocks at the enemy that were dealing the Brigade such punishment. At the end of the fighting on this part of the line, almost two hours later, the Irish Brigade marched away leaving some 550 men dead on the field.

The sunken farm path where their opponents lay stacked in heaps has been known ever since as “Bloody Lane.”

Antietam so damaged the Brigade that two more regiments, the 28th Massachusetts and the 116th Pennsylvania, also mostly Irish, joined the Brigade before the next engagement, just three months later.

On December 13, 1862, the Union Army once again attacked the Confederates. This time Lee was not scrambling to reassemble his far-flung divisions, he was dug in and waiting for the Union assault.

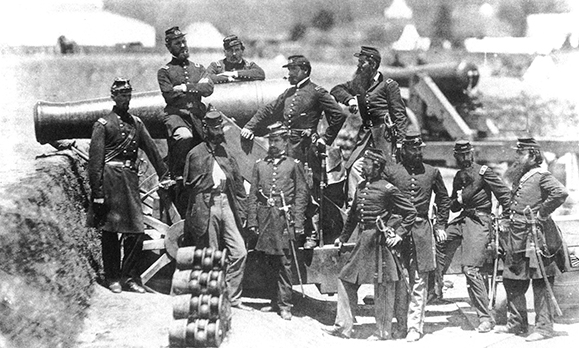

The Army of the Potomac, under the dubious command of General Ambrose Burnside, obliged Lee with a series of frontal assaults against the southern fortifications on a ridge just south of Fredericksburg known as Marye’s Heights.

The Confederates had placed artillery all along the heights. At the base of the hill, in yet another semi-sunken road, stood resolute Confederate infantry.

To approach this formidable position the Union infantry had to cross some 600 yards of open fields.

In defiance of common military sense and some might say a sense of decency, General Burnside hurled no less than six major and eleven minor attacks against the impregnable Confederate emplacements, all of them dismal failures.

After standing under arms all morning, the Irish Brigade was addressed by Brigadier General Thomas Francis Meagher. In eloquent words, he reminded his soldiers that they were Irish and that every eye in the Union would be on them to see how they upheld their fighting Irish tradition.

The flags of the three New York regiments had been so fiddled in previous battles that they had been sent to New York City for repair. To be sure that the enemy knew that it was the Irish Brigade, Meagher ordered sprigs of evergreen to be placed in the caps of both officers and men, himself setting the example.

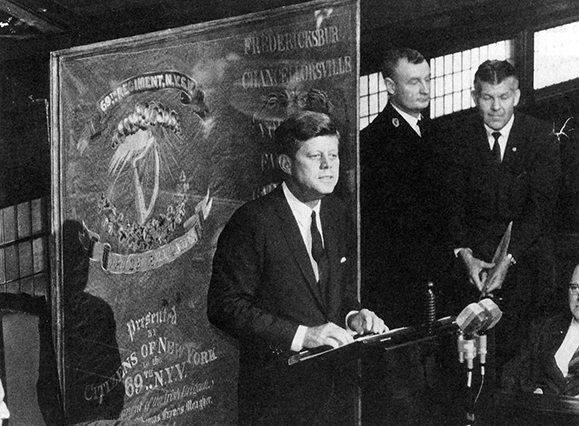

The Irish marched forward under a single green banner, that of the 28th Massachusetts, which had recently been presented to it.

They moved out into Hanover Street and under intense fire reached a canal that was supposed to have been bridged; the men plunged into the ice-cold water to cross. The rising slope of Marye’s Heights lay ahead. The Irishmen rushed up the hill with wild cheers. General Meagher had led the Brigade to the field but did not join the charge because of an injured leg. The five infantry regiments advanced with the green flag of the 28th Massachusetts in the center flying and flapping in the breeze.

They had not gone far when they were struck by heavy artillery. Shells burst in front, in the rear, above, and in the ranks. Holes opened in their fine, but the Irishmen pressed forward. The Union wounded littering the ground cheered them on.

The stone wall was defended in part, by Confederate General Thomas R.R. Cobb’s Georgia Brigade, many of whom were Irish immigrants. As the Irish Brigade closed on its position, these Confederates recognized the green flag of the 18th Massachusetts and the symbolic sprigs of green in the caps of their opponents.

Private William McCleland, of the 88th New York Infantry, later wrote, “Our men were mowed down like grass before the scythe of the reaper…The men lay piled up in all directions. And still, they forged ahead.”

A strange sound was heard above the screams of the wounded and the exploding artillery shells. The Rebels were cheering the bravery of the Brigade. General George Pickett, best known for his charge at Gettysburg, wrote after the battle to his fiancee, “Your soldier’s heart almost stood still as he watched those sons of Erin fearlessly rush to their death. The brilliant assault on Marye’s Heights of their Irish Brigade was beyond description. Why, my darling, we forgot they were fighting us, and cheer after cheer at their fearlessness went up all along our lines.”

Finally, some thirty yards from the Confederate line, the command to lie down and fire passed through the surviving men. They had advanced further than any other Union unit that day, and further than any would. Thus none could relieve them and only the cover of darkness saved those that lived.

As the sun dropped below the horizon it cast eerie shadows across a carpet of blue – the bodies of some 9,000 Union soldiers. And lying the closest to the entrenched Confederate positions were long lines of Irishmen with green sprigs of boxwood in their hats.

The 28th Massachusetts lost 158 of the 416 men who followed their colors up the bloody slope that winter day. The death toll fell with equal weight among all five regiments of the Brigade. Overall they suffered a total of 535 casualties or two-thirds of the strength that they carried into the fight.

General Edwin Sumner, commander of the II Corps, riding along the lines the next morning as the units were reforming, rebuked a man of the 28th Massachusetts for not being in company formation with his comrades. The Irish private looked up at the general and replied, “This is all my company, sir.”

Nearly one year of unremitting fighting had decimated the ranks. The three original regiments had numbered close to 2,500 men when they left New York City in 1861. On the eve of the Gettysburg campaign, the combined strength of the three regiments was 240 men. The 28th Massachusetts, which had transferred to the Irish Brigade in November 1862, counted only 224 men. Disease and casualties had reduced the 116th Pennsylvania, a mixture of Irish immigrants and native-born Germans, to 66 men. In all, the Irish Brigade mustered 530 men present for action on July 2, 1863.

The Irish brigade had lost its commanding officer and founder just two months earlier.

Brigadier General Thomas F. Meagher had repeatedly petitioned headquarters for permission to recruit replacements for the Irish Brigade. He resigned his commission in protest on May 8, 1863, after the Brigade lost one hundred more men at the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 1-5.

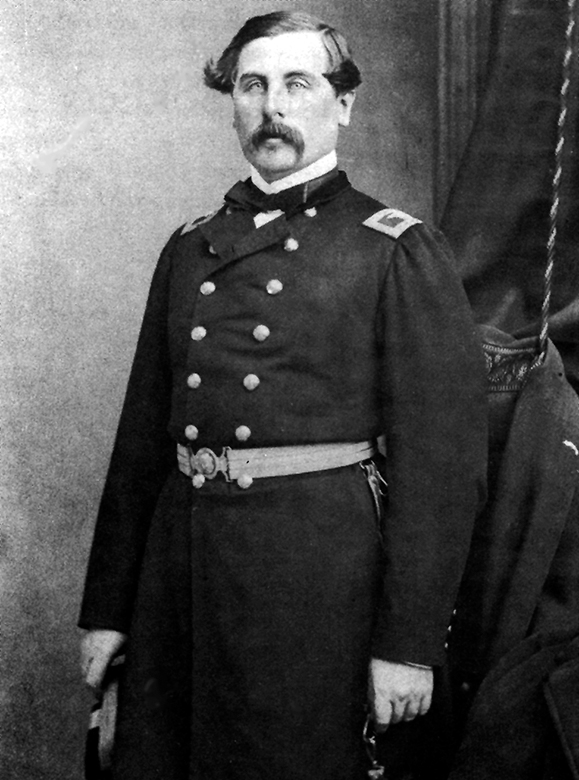

Colonel Patrick Kelly took command of the dispirited Irish Brigade after General Meagher’s resignation. Kelly had been a farmer in County Galway before he emigrated to America in 1849.

The march to Gettysburg was one of the longest and most severe ordeals that the soldiers of the Irish Brigade had faced. On some days the men marched 15 miles and on others 18; on June 29, a distance of 34 miles was covered. Along the way, they passed grim reminders of the battles they had fought. Private William A. Smith, 116th Pennsylvania, wrote his parents: “I came over the battlefields of Bull Run and Antietam and seen the brains of the dead on the field that was not half-buffed.”

On the morning of July 2, Kelly’s men filed off towards Gettysburg and, shortly, reached the Union defensive line at Cemetery Ridge near Plum Run.

The first day of the battle had gone poorly for the Union side, with three of their corps badly torn up and thrown back against the town. The second day opened with the Union soldiers hanging onto the high ground to the south and east of the town. Regiment after regiment was fed into the fight piecemeal as they arrived in the area, yet still, the Confederates threatened to break through and turn the battle, and potentially the war, in their favor.

Into this chaotic swirling mass of men, material, and munitions strode the remnants of the proud Irish Brigade. They were to counterattack across an open wheat field. No other units were available, all being already committed or thrown back in retreat. Only the Irish stood between the Confederates and victory.

Knowing that they would be going in alone, the Brigade knew the odds were against them. Their chaplain, Father William Corby, had them kneel and issued a mass absolution, just a few hundred yards from the enemy. Then the Irish attacked.

Kelly’s men swept rapidly through the waist-high wheat in two ranks, with their green regimental flags flying and their weapons at “right shoulder shift.” Lieutenant Colonel Elbert Bland of the 7th South Carolina remarked, “Is that not a magnificent sight?” to his commanding officer as he watched the Irish Brigade closing on his position.

The attack succeeded. It bought the Union army a few desperate minutes to bring in yet more units, but the cost was the heart and the soul of the Irish Brigade. After suffering, once again, close to 50 percent casualties, the “Irish Brigade” would never be the same. Although replacements and supplemental regiments would refill the ranks, the uniquely Irish nature of the Brigade died there on the wheat field at Gettysburg.

By the end of the war, more than 4,000 men of the Irish Brigade had been killed or wounded on the battlefield; more men than ever belonged to the Brigade at any one time. With their blood and courage, they carved a reputation for valor so deeply into the heart of their adopted nation that there would never again be a question as to whether the Irish had the right to call themselves “Americans.” ♦

I’m from Dublin & living in Waterford. There is a statue of Thomas Meagher in my city & I had NO IDEA who this man was. I had to stop reading so many times to wipe my eyes with tears of pride & sadness.

Brilliant!!

Thanks you

Here the day after St Patrick’s day 2021 – so many in the USA today don’t know the history of these brave men. God Bless Them – and has been said in many Irish prayers – open the gates of heaven to them. There would be No America – and No world like we enjoy today without their sacrifice.