The wood-paneled wall of Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall opened like the ribcage of a Leviathan. And two giant voices emerged. One was the drone of the pipes, the other was of the human tongue, the decibels of high and low that make poetry. Both were ancient, borne into the present and burrowed deep in the listeners’ bones. The audience hushed.

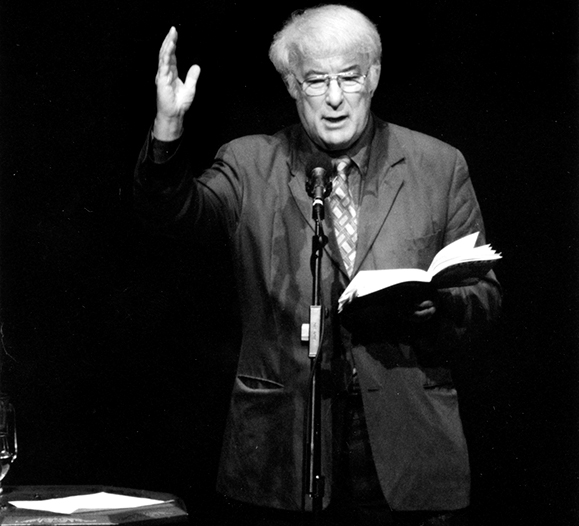

And then the cotton-haired one spilled his glass of water. All laughed at the sprinkle, but by the end of the night we would all be doused in the spirit that flowed through the master’s lips.

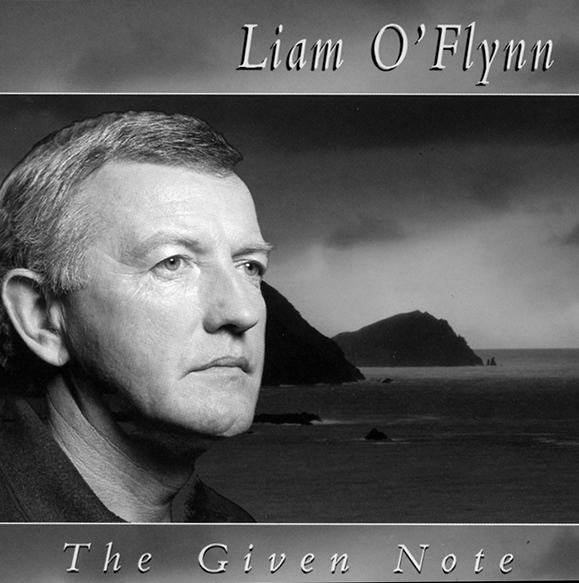

When Nobel Prize-winning Irish poet Seamus Heaney and renowned uileann piper and founding member of Planxty Liam O’Flynn take the stage together, to call such a night a mere poetry reading or concert is inadequate. The moment is immense.

Of course, neither would admit to their being the cause of all the goosebumps in the room. But they may indicate the other to be the reason. The sheer down-to-earth quality of these two men is refreshing and awe-inspiring. Each is as humbled by the rhythms he weaves as those fortunate enough to hear. Their mutual respect is endearing and was apparent as Heaney later read a poem he wrote in dedication to O’Flynn, who is considered a living embodiment of a tradition stretching back 300 years. The poem, entitled “The Uileann Pipes,” reads in part:

Liam O’Flynn says

that the only English rhyme

For the word “uileann” –

From Irish uile, meaning

Elbow – is the word “villain.”

Ag seideadh, pronounced

“Ig-shade-oo” (or near enough)

And meaning “blowing” –

Used of great biblical winds –

Means also “to play the pipes.”

The solicitor

Questioned the dying master

One last time: “You want

To leave your pipes to that man?

Why’?” “Because he can play them.”

Thursday evening, May 29th, was the first in Lincoln Center’s celebration of Seamus Heaney, part of the Great Performers series at Lincoln Center, and the line outside gave it all the appearance of a premier. The next night would feature Heaney reading from his new translation of Beowulf, while the following three nights would offer performances of The Diary of One Who Vanished, a song cycle by Czech composer Leos Janacek which Heaney translated.

The sage-like Mr. Heaney, after knocking over his glass of water, said of the concept for the evening and the soon-to-be released Claddagh recording of the same name, The Poet and the Piper, “It’s very simple. He plays some tunes, I read some poems.” Simple idea; the effect was transporting.

The presence these men brought with them is not so easily named. It was a presence that could best be described as a link, a tangible link if music and words be tangible. O’Flynn and Heaney certainly form the link between worlds, of here and there, of the past and the present, the spirit and the material.

It was a theme introduced immediately by Liam O’Flynn’s rendition of “Song of the Spirit.” Fittingly, O’Flynn explained that the tune is said to have come from the spirit world, carried by the breeze off the Blasket Islands.

Heaney follows and speaks of a “sunken kind of love” that permeates Irish literature and thought, such as the love between a father and son. He talks about his own father and reads “A Kite for Michael and Christopher,” a poem about his relationship with his own sons.

The sunken love theme surfaced again in “Mossbawn” from North: “And here is love/like a tinsmith’s scoop/sunk past its gleam/in the meal-bin.”

Perhaps the best pairing of the evening came when O’Flynn played the soulful “Brendan’s Voyage,” a piece that captures the mystical journey of the sixth century saint.

O’Flynn’s pipes seemed to be sending Brendan’s adventurous spirit itself whipping through the auditorium.

The kind of presence that Heaney describes perfectly in “Lightenings”: “When the monks of Cloinmacnoise were all at prayers inside the oratory, a ship appeared above them in the air.”

The poem speaks of a man whose anchor is stuck, who “can’t bear our life here and will drown.” The abbot responds, “unless we help him.” Released, “the man climbed back out of the marvelous as he had known it.”

Like two shamans, like two monks, Seamus Heaney and Liam O’Flynn freed a small corner of upper Manhattan that night, allowing our ships to soar to where, as Heaney writes, “the soul cloud-like roams.”

Thank you, Mr. Heaney and Mr. O’Flynn. We’ve not yet touched ground. ♦

Leave a Reply