How a committed sister freed her brother from prison.

In 1980 the body of Katharina Brow was found in her trailer home in Ayer, Massachusetts. She had been stabbed to death and robbed of money and jewelry. Suspects were questioned but the case languished for two years until an anonymous phone call tipped the police that Kenny Waters had admitted to the crime. Kenny already had a reputation for being rowdy and had had a few run-ins with the police. In fact he had broken into Brow’s house when only ten.

Even though Waters had an alibi – he had worked a double shift the night of the murder and had to appear in court the next morning to answer to an assault charge – his defense fell apart in the court room. Two former girlfriends testified that he admitted to the murder and another witness testified that Kenny had sold her some of Brow’s jewelry shortly after the murder. Blood found at the crime scene that was believed to be the killer’s matched Kenny’s blood type. He was convicted on May 12, 1983 and sentenced to life in prison. And the wheels of justice rolled on.

Except for one thing.

They had the wrong man.

And Kenny Waters had one very valuable ally.

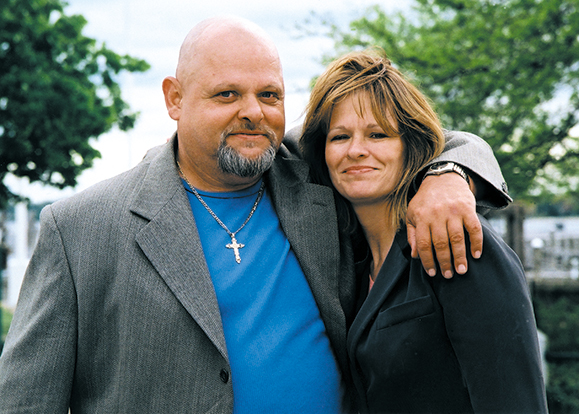

In 1998, Betty Ann Waters, Kenny’s sister, graduated from Roger Williams School of Law and passed the bar exam. She had overcome tremendous odds to reach this point and had only one motivation, one case to prove – her brother’s innocence.

In his first few years in prison, Kenny sank into a deep depression. He earned the nickname Muddy Waters because, as he says, “I was living the blues.” As a form of passive resistance against his imprisonment he refused to clean his cell. “I had the filthiest cell for nineteen years. I got locked up [in solitary confinement] many a time for that.” His resistance to his fate took on a darker, less passive form in his various suicide attempts, slashing at arteries in his wrists and legs.

Seeing her brother slip downhill, Betty Ann took action and in 1986 the two came up with what Kenny calls “a master plan”: “She would go to law school if I would stay alive. That was the deal we made.”

Betty Ann had no interest in a legal career, but this seemed to be Kenny’s only hope. The family had already blown their savings paying lawyers to appeal his conviction and after all they had been through, they weren’t sure they even trusted lawyers anymore.

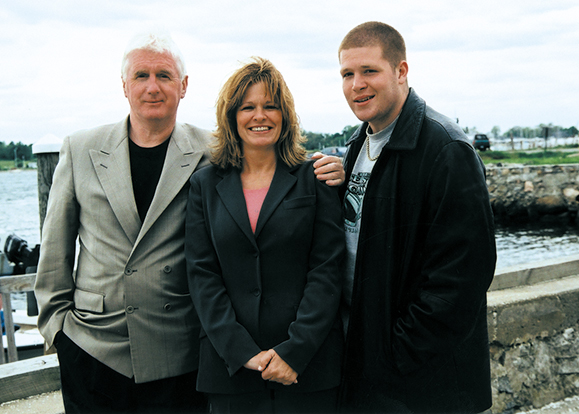

“I just felt I had to. I felt I had to try,” Betty Ann explains quite simply. She, Kenny and I are sitting in a booth in Aidan’s Pub and Grub in Bristol, Rhode Island. Kenny offers a different motivation for her efforts to free him. “We hung around together all our lives…she owes me!” he jokes.

The odds were against her. A mother of two young boys, Betty Ann had only a GED and a few college credits. Prior to her, no one else in the family had ever been to college. But if anyone could pull it off, it was Betty Ann.

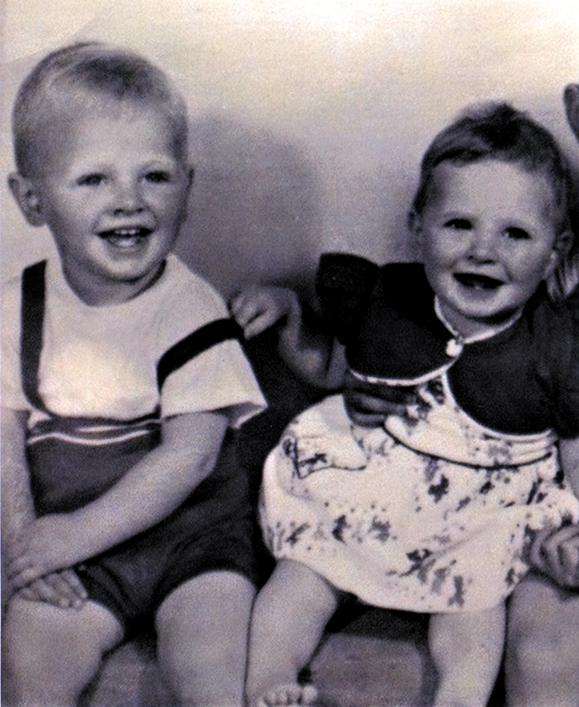

“Since she was a little girl she’s taken care of that family,” observes Abra Rice, Betty Ann’s friend from law school. “She’s the anchor.” The fourth child in a family of nine, Betty Ann was the oldest girl. There were nearly as many fathers as there were children the first six kids were born in less than six years but Betty Ann and Kenny’s mother largely raised her children on her own with the help of her parents. She lived in a small house on their farm with the girls, while the boys stayed with their grandparents up the hill.

“She was never on top of things, she never knew what we were doing. When we were little, we basically did whatever we wanted.” There’s not much that Betty Ann has to say of her childhood that she’s willing to see in print, but suffice it to say that her home life as a child was chaotic at best.

When she was twelve, she and three other siblings were placed in foster care for three years. She and her sister stayed together for the first two as they were shuffled from home to home, but were ultimately separated when placement for two children became hard to find. “I don’t want to get into it,” she says, sadness edging her voice, “but various things happened that we had no control over.”

When asked why she dropped out of high school at age sixteen, her reticence again comes to the fore. “My home life was not conducive to school or studying.”

In the state of near anarchy that was home, Betty Ann was the one who tried to hold everything together. It’s hard to get her to talk about her childhood (“I have a hard time talking about myself,” she laughs nervously), but when pressed she finally admits, “According to my brothers and sisters, I was like their mother. I was always the one saying don’t do this or don’t do that. For instance if you were out too late or hanging out with the wrong people I’d be the first one to stop you or make you go to school.”

Musing on her role in the family, she explains, “Maybe it’s that I was the first girl. Not that I was perfect at all – we were called The Little Rascals growing up – but even at twelve, I was more rational. And I always tried to help my younger brothers and sisters. My mother had two other children after I was twelve and I always took care of them. I have a brother who’s 35 now and we’re very, very close. To this day when he thinks of his childhood, it’s me [he thinks of]. I was the first one who took him to Disney World.

“I also have one sister younger than him who said if it wasn’t for me she wouldn’t have finished high school. She was flunking English and doing all these things. Her punishment was she had to live with me,” she laughs. “I made her do all her work. I went to her English teacher and found out all the work she had to do in the past and made her do it.”

In a family that did not place great importance on education she stood out in her determination to go back and get her GED and her refusal to let her younger brothers and sisters drop out. “I was different,” she admits. “I don’t know where it came from, but somewhere along the way I knew I wanted to do something different. Not so much that I knew the right choices, but I knew the wrong choices and didn’t want to make them.

“I always felt [education] was the way out or the answer to things. We had no other way out. Nobody had any money,” she explains.

As if putting herself through college and law school simply to free her brother wasn’t enough of a herculean task, Betty Ann’s life was made more difficult when her husband walked out on her in 1989. She was just shy of earning her Associate’s Degree from Rhode Island Community College.

The divorce was finalized a year later. “He didn’t like the idea of me going to school,” she explains. “He wanted to control me.” Kenny chuckles, “There’s no controlling her.”

Her anger toward her former husband is still very real, and she doesn’t mince words. “It’s not just being single without him [that was so hard], it was that he was a pain in the ass. He always took me back to court for something, mostly it was child support. He thought I should work more so he could pay less, but with the way the laws are he has to pay the same no matter what.”

Betty Ann transferred to Rhode Island College where she earned her Bachelor’s degree. To make ends meet she tended bar, keeping her books with her to read during slow times. This habit attracted the attention of one of the managers, Aidan Graham, a native of Mullingar, County Westmeath. She in turn was charmed by his accent. Her Irish-born grandmother would often tell stories of her hometown in Kenmare, County Kerry, and Irish relatives often came to visit. “All we knew was the Irish brogue,” Betty Ann laughs. She herself has been to Ireland three times, traveling to see her grandmother’s childhood home in Kenmare.

Betty Ann and Aidan began a relationship a year after her divorce. In Aidan, she finally found a partner who completely supported her ambitions. “He was totally behind me going to law school and helping Kenny,” she recalls. “He’d go up and visit Kenny and send him money and talk to him on the phone, all for me.”

She in turn helped him start a pub and restaurant of his own in 1992, Aidan’s Pub and Grub in Bristol. He quickly branched out and now owns three restaurant/bars in Rhode Island. Although they broke up a year ago (“We’re taking a break from each other,” she says) she still wears the antique engagement ring he gave her, and all throughout our interview at his pub he hovers close by. “He’s still my best friend,” she later admits.

As Betty Ann worked her way through college one dilemma loomed large. Would she be accepted to law school and if so, where would she go? The closest law schools were in Boston, an hour and a half away. The fates seemed to smile on her efforts when, in 1993, Roger Williams University opened a law school in Bristol, only minutes from her home. She was accepted and enrolled as a full-time student in 1995.

Preparing for the first and toughest year of law school, Betty Ann suffered another setback when her husband dragged her back into court for custody of the two boys. She relented. “I had to let them go. I let them go live with him for who knew how long. It ended up being a little over a year they begged to come home.” She barely suppresses a giggle.

And while having the boys live away from her did allow her more time to study on the weekdays, she sums up the experience succinctly, “It was bad. I would rather have had them with me.”

Did she ever want to give up and pack it all in? “Many times I thought I couldn’t do it,” she says. “The goal of going to school was to get into law school and I kept thinking what if I don’t get in? But I learned that if you put one foot in front of the other and just keep going, you get there.”

The fates once again seemed to smile on Betty Ann’s efforts when during her Second year of law school she learned of the work of The Innocence Project while researching the use of DNA in post-conviction releases. Co-founded by lawyers Barry Scheck and Peter Neufield, The Innocence Project offers inmates pro bono assistance to challenge convictions with new DNA evidence. Betty Ann began barraging their offices with letters asking for help and advice.

Amid the thousands of requests for assistance the Innocence Project gets each year, Betty Ann’s stood out. As Scheck recalls, “A lot of what drew us to the case was Betty Ann, the intensity of her feeling about her brother’s innocence and her indefatigable energy.

“She has a way with people,” he continues. “She makes people want to help her. She just has that gift.”

And, of course, it helped that she did her homework. Upon graduating from law school and officially becoming her brother’s attorney, Betty Ann launched her own investigation into Kenny’s case, questioning anyone who had any connection to the case and the initial investigation, from the investigators to the witnesses to the appeals lawyers. She also called the courthouse to find out if there was any DNA evidence left over from her brother’s trial and convinced one court clerk to rummage through the courthouse basement until he came across an old cardboard box with Kenny’s name on it. It contained the evidence from his trial that legally could have been thrown away years ago.

Inside the box she found a blood sample taken from the scene of the crime that was believed to be the perpetrator’s. It was Kenny’s only hope.

In November 1999, Scheck asked the Middlesex district attorney to test the blood sample and compare it to Kenny’s DNA. This past March the results came back – Kenny’s DNA didn’t match up. Instead of exonerating him then and there, the courts only vacated his conviction, placing him back under indictment and allowing him to go free on bail while they decided whether or not to retry him.

At the time of our interview the courts still had not reached a decision. Since the case was still open Betty Ann could not speak freely about what went wrong with Kenny’s first trial. “I’ll just say that the system didn’t operate the way it’s supposed to. There were just so many errors that are really obvious now looking at it. It was obvious to us then, but it’s obvious to everyone looking at it now. I don’t think it should ever have gone to trial. I thought it back then and I think it more-so now.

“It’s like they picked Kenny and gathered evidence around him,” she continues. “They had Kenny because of an anonymous phone call two-and-a-half years after the crime and then they went about getting evidence to fit Kenny. That’s not the way you’ re supposed to do an investigation. You’re supposed to go into it objectively.

“We used to bang our heads against the wall asking how could these people try you on the evidence they had?”

In the meantime, Betty Ann is continuing her investigation, preparing as if Kenny really were going on trial. If he does, she is confident that he will be acquitted based on the DNA evidence.

She could rest easy, perhaps congratulate herself for the fact that her brother will not be going back to jail, but she won’t. “He is [free],” she acknowledges, “but he’s not going to feel free until they say `you’re exonerated.’ It’s like something’s hanging over his head.”

Once this is all over will she remain in law? “Not in the traditional sense,” she replies. “I want to do something with my degree, but I definitely don’t want to be in a courtroom defending lawsuits and criminals. I want something more meaningful.” She would like to help establish a Rhode Island branch of the Innocence Project in cooperation with the Roger Williams School of Law. And, of course, she still does administrative work at Aidan’s in order to pay the bills, as her legal work so far has been pro bono.

Given the frantic pace she keeps, she’s not one to bask in how far she’s come. Instead she remains focused on all that’s left to do. In discussing how she feels now that her brother is out of jail, she admits, “It’s not real yet. Thinking back to the time when I said I was going to law school and now we actually did it and he’s out – it’s surreal. I’m so used to falling asleep with books around me, it’s kind of funny just falling asleep with the TV on now.”

I ask about how her children have been affected by her one-woman crusade.

“I try to put myself in their shoes, but it’s hard. Richard was a year-and-a-half when Kenny was arrested and Ben wasn’t born yet. So all they know is, I’m going to school to get Kenny out and it’s Uncle Kenny on the phone. The last couple of years as they started to get older they’d ask, `Is Kenny ever getting out?’ and `When is Kenny getting out?'”

The rest of her seven siblings supported her efforts, but were afraid to hope. “Because we had been let down so many times, I think that they didn’t think I’d be able to do it,” she observes. “They wouldn’t say it, [instead] they would question things all the time.”

After all she’s been through, one might expect her to be hardened, but she’s quite the opposite. While she undoubtedly can be determined and driven, she has a sweetness and vulnerability that is compelling. When she relaxes she can be playful, almost flirtatious and her smile is magnetic. “She is the kindest, most generous, most compassionate person I’ve ever met,” Abra raves during a telephone call. “She’s amazing.”

She’s managed to pack more accomplishments, more life into the past twenty years than most people do in a lifetime, but years of struggle have come at a price. “I lost faith,” she points out.

“In God?” I ask.

“I won’t say God, but the system, the people. I don’t blame God for anything. I blame the people. I definitely lost faith in the system. Right up until the day he came out, I still thought something was going to happen to keep him there.

`[The system] needs to be revamped,” she points out. “It needs more checks and balances. Too many people who aren’t qualified have too much power. It’s amazing what power the prosecutors and police have.

“I don’t have a lot of faith in prosecutors,” she continues. “It’s like we’re on different sides, and it shouldn’t be. It should be that we’re all for justice, and I don’t feel that way at all. I feel like they’re on a totally different side, a whole different train of thought. It’s difficult operating in a system when you feel that way.” Yet, one can’t help but think that her relentless idealism and tenacity would be very welcome in the legal profession.

She’s already late for her next appointment at the courthouse in Providence. She reapplies her lipstick, fusses over who drives Kenny home, then grabs her bag and dashes out the door. When she’s safely out of earshot Kenny states, “I knew she’d make a great lawyer. She always won every argument when we were growing up. She always got the last word.” ♦

I know Aiden Graham and Betty Ann- both incredible people. It’s so sad what happened to Kenny after his release.