Will a re-examining of the Ulster Scots advance the idea of a “pluralist society” or lead to further separation?

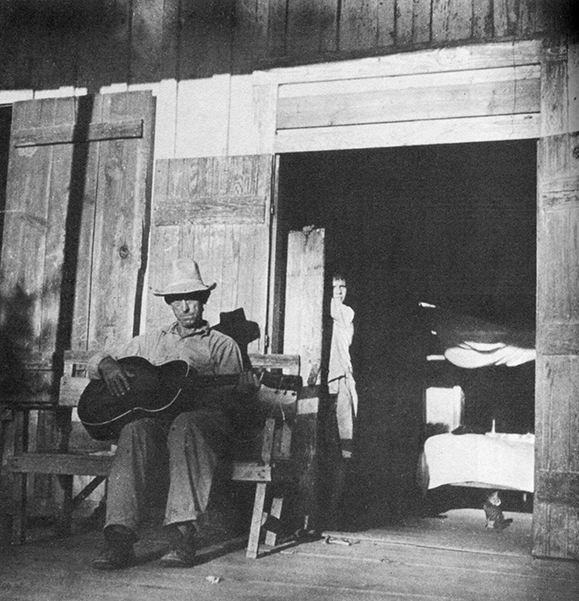

Southerners like to say they are not like other Americans, and often base that claim on their characteristic ways of talking, storytelling, preaching, dancing and, above all, playing country music. But few of them realize that those very qualities can be traced back to the traditional folkways carded with them by the Celtic settlers of the South, most of whom were originally from present-day Northern Ireland.

Despite the fact that the Scots-Irish were one of the dominant groups in the American colonies, and remain one of the largest ethnic groups in the American South, relatively little is known about them, especially in comparison with the Irish of largely Catholic background who came to the United States following the Great Famine of the mid-nineteenth century.

The Scots-Irish immigration pattern started over a century earlier, and that distance in time erased many memories of the old country. But another, more telling reason for the memory lapse is that the Famine immigrants landed mainly in the large cities of the North where, in reaction to poverty and prejudice, they formed cohesive communities of their own. In politics, religion, education, popular entertainment and the arts, Irish-Americans developed a culture that ultimately had a huge impact on this country. Think of George M. Cohan, Eugene O’Neill and Bing Crosby, as well as the green beer and plastic shamrocks of St. Patrick’s Day shenanigans and you’ll know what I mean.

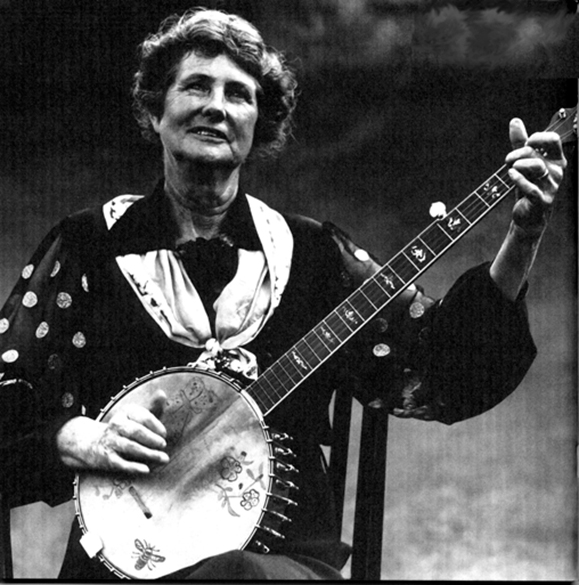

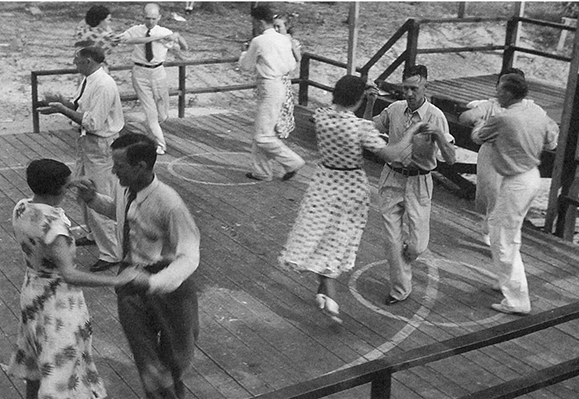

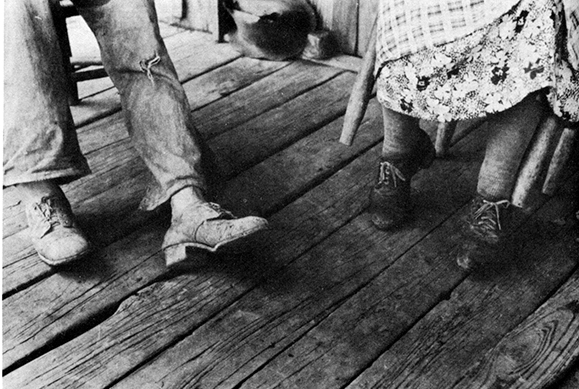

Here in the South, however, where the Scots-Irish spread themselves out across the lush green valleys and mountains of the backwoods frontier, bound together only in a loose network of fiercely clannish and religious ties, their isolated lifestyle remained closer to that of rural Ireland. Think of home-grown entertainments such as country fiddling, along with clogging, square dancing and tall tales told around the fireside, and you’ll know what I mean.

In Northern Ireland, the current peace process has led to a reexamination of the Scots-Irish heritage and, in particular, the underlying reasons for the tension and strife between two peoples who, for almost 400 years, have lived side by side in a relatively small area while barely acknowledging the presence of the other.

Or is that entirely so? The Academy of Irish Cultural Heritages, recently, established at the Derry campus of the University of Ulster, has set out to explore in a scholarly and artistic forum the commonalities as well as differences between the two communities of Northern Ireland. Robert Welch, Dean of Humanities at the University and a brilliant student of Irish literature, history and politics, says the chief aim of the Academy is to advance the idea of a “pluralist society” based on cultural diversity.

In keeping with this ambition, as well as the “parity of esteem” espoused by the Good Friday Agreement as a necessary condition of lasting peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland, the Academy of Irish Cultural Heritages will include an Ulster Scots Institute.

This will be a study center designed to promote a better understanding of Scots-Irish history, culture and heritage within Ulster (the ancient kingdom of Northern Ireland) and beyond to those regions of the world which have been influenced by the people who left Ulster in order to seek a better life. Naturally, the Institute will place a particular emphasis on studies relating to the American South.

Within an Irish context, virtually everything takes on a political cast, and this emphasis on the culture of the Scots-Irish is no different. Willie Drennan, a musician, storyteller, musical arranger and cultural activist, is the founder of the Ulster Scots Folk Orchestra. Six members of the orchestra traveled to Atlanta last March to participate in a concert at Emory University, the final event of an international symposium on the Southern impact of the Scots-Irish diaspora sponsored by the W. B. Yeats Foundation. Willie says that the musical heritage of the Ulster Scots has been submerged because his own people confused it with traditional Irish music. “For a long time, I was actively discouraged from playing our music, but now there’s a huge interest in it, especially in the Republic of Ireland,” he said. Willie takes tremendous pride in the role that his music has already played as a bridge between Protestants and Catholics alternately in a local Orange Lodge and a Catholic community center in Ballymena. “The audiences in both places are mixed,” he said, “whereas a few years ago, they would have been completely segregated by religion and politics.”

Not everyone approves of this new development in Northern Ireland. A friend of mine, who happens to have been the first Catholic producer ever appointed at the BBC-Belfast, argues that the emphasis on a distinctive Ulster Scots musical tradition is potentially dangerous because it reinforces the separatist position of hard-line Loyalists.

“I support the idea of exploring the extraordinary Scottish influence on Irish music in Ulster,” says my friend. “My own grandmother was a Presbyterian, of Scottish background, and from my childhood home in North Antrim you can see the coast of Scotland just nine miles across the water. But the Northern (music) tradition is neither Catholic nor Protestant, neither Loyalist nor Nationalist, for it predates the partition of Ireland. Instead it belongs under the wide umbrella of Irish folk song and is continuous with songs throughout all of Ireland that have been shaped by many different cultures, but one nonetheless distinctively Irish.”

Music is only one aspect of the controversy instigated by the new emphasis on the Ulster Scots heritage. Even more opposition is raised by the effort to establish Ulster Scots, the traditional speech of the Border Counties of Scotland, as a language on par with Irish and the Gaelic of the Highland Scots. Some scholars argue that “lallans,” or Old Scots, the literary idiom employed by Robert Burns, Hugh MacDiarmuid and other Scottish poets, has existed as a distinctive language for more than a thousand years, while others claim that it is merely a dialect in English. “What is a language, after all, but a dialect with an army behind,” says one Loyalist. “Unfortunately, we’ve lost the war.”

The reference is to the growing awareness among many Loyalists that the umbilical cord with England has been broken. Despite the years of fanatical loyalty to the values sustaining the Empire, to thoughtful people that stance is now just an embarrassing anachronism. That would seem to be a victory for the Nationalists, but old ways die hard among stubborn Ulstermen. Anyone with a feel for the rigid loyalties of kirk, kith and kinship practiced in the Old American South should understand that. As the country preacher once proclaimed: “Lord, grant that I may always be right, for Thou knows I am hard to turn.”

Southerners also know something about loss – loss of pride and place in the aftermath of bloody defeat. It saddened me a few weeks ago, when several of my Emory students admitted that they had deliberately lost their Southern drawls in an effort to avoid the ridicule of their more cosmopolitan colleagues. Yet these very students are the ones who connect most deeply with Irish traditions like the “dinnshenchas” – folklore, mythology, poems and songs that create a fierce attachment to the particular landscapes that define home. It was a woman of mixed Irish and Scots-Irish descent, Margaret Mitchell, who, at a dark time in Southern history, bore witness in Gone With the Wind to the “dinnshenchas” of her people and their desperately tortured history.

Michael Montgomery, one of the leading authorities on the story of the ScotsIrish in America, has observed that “historians have written much on them and disagreed widely, frequently and passionately.” These disagreements take on a tragic light in view of the conflicts that still trouble Northern Ireland. But I can’t help thinking that at last a new dawn of hope is rising over that beautiful landscape that has witnessed so much suffering and sorrow in the past. I also believe that the people of the American South, inheritors of the legacy of Martin Luther King as much as those fabled Scots-Irish warriors Andrew Jackson, Sam Houston and Daniel Boone, have much to share with their cousins back in Northern Ireland.

For, as Congressman John Lewis responds when asked if he does not hate the people who broke his skull 35 years ago on the bridge at Selma, Alabama, “No, I say now as I did then, `We must teach them to love themselves.'” Love of that order can only be sown with forgiveness as well as a deep-rooted recognition, understanding and appreciation of shared cultural traditions. Southerners know that in their very bones, for over time they have learned to tend their beloved gardens patiently and well. ♦

Good article, thank you!