“Sometimes it is a spiritual experience, but most of the time it’s not…You have to work very hard to get that. But that’s okay. There’s no free lunch, y’know?”

– Van Morrison

Leave it to Van Morrison to lend a bit of welcome perspective at the end of From a Whisper to a Scream, a three-hour history of Irish pop music, originally produced for RTE, now available on video. Produced by David Heffernan and Bous de Jong, the film is an ambitious, occasionally breathless survey of the ascent of Irish rock music. It’s chock full of terrific archival video clips – Rory Gallagher tearing down the walls on the German pop show Rockpalast, Horslips, in full codpiece regalia, rocking full-throttle at a mid-seventies festival, an early U2 clip with a moppetish Bono providing interpretive mime.

From a Whisper begins with the showband phenomena of the fifties and early sixties – a clip of a young Brendan Bowyer doing an Elvis turn is priceless. The showbands crisscrossed the country, recreating the big hits of the day, offending few (given the huge sway the Catholic Church had over Ireland at the time.) As filmmaker Jim Sheridan opines, “It wasn’t as if they were confined in where they got their inspiration. It was just that their inspiration stopped short of believing there was any worth in their own culture.”

But there were a few Irish musicians, emboldened by the successes of groups like the Beatles (there’s a great clip of Paul McCartney telling an RTE reporter “hey listen, we’re Irish too” as the Fab 4 land at Dublin Airport in ’63), who pushed the musical and societal constraints and laid the way for U2.

Bluesville was the first Irish pop band to break through in the U.S., charting at #7 with “You Turn Me On,” in 1964. They were soon followed by The Them, Van Morrison’s first band. “Here Comes the Night” and “Gloria” were instant rock classics.

But Morrison was a restless sort – he grew frustrated at the three-chord template most bands were following at the time. He split from The Them and headed to New York, where he drank deeply of American jazz and blues. Assembling a cache of crack musicians, Morrison recorded the mesmerizing Astral Weeks in 1968. “It came from heating people talk – it was the rhythm of speech,” says Morrison on-camera, of the seminal work.

Of Astral Weeks, U2’s Bono (who gets a lot of airtime on Whisper) says the work was like “legal drugs.” Indeed, its improvised explorations and live feel – many of the songs were captured on the first or second take – provided a roadmap for Morrison’s chameleon-like career: he achieved success on his own musical tastes and terms, and shunned the limelight. It’s quite the coup for Heffernan and de Jong to have Morrison contribute so heavily to From a Whisper.

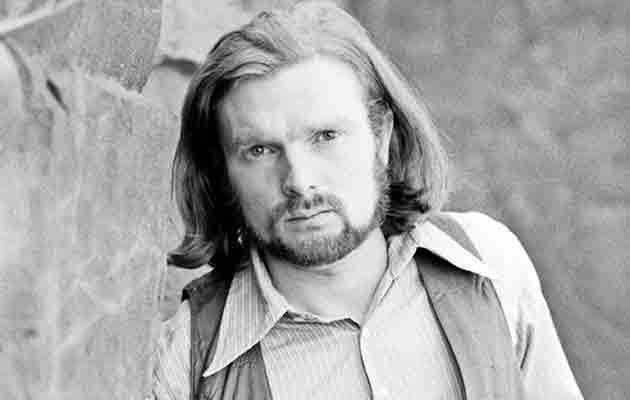

Rory Gallagher’s live shows were legendary, first with Taste and later as a solo artist. Gallagher dripped fire

and sweat into tunes like “Bullfrog Blues” or “Souped Up Ford.” A film clip of Gallagher on Gay Byrne’s Late Show wringing gut-wrenching slide licks from a National Steel guitar best illustrates the Cork axeman’s commitment and skill.

As hard as he worked – Gallagher played upwards of 200 concerts per year – he never broke though to wide commercial success, perhaps due to his unwavering devotion to the blues form. “Whenever he hit a chord, he vanished to a place where every artist should be,” says author Pat McCabe of Gallagher.

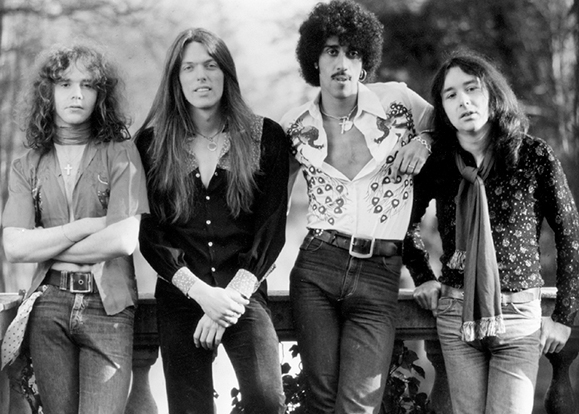

At roughly the same time as Gallagher was forming Taste, a mixed-race Dub named Phil Lynott was forming his own high-energy outfit, Thin Lizzy. Lanky, good-looking, and never one to shun excess, Lynott oozed rock-star confidence from his grown-out afro to his platform shoes.

When Lynott reworked “Whiskey in the Jar,” made famous by the Dubliners, he was reclaiming the Irish bardic tradition and melding it onto a new rock groove. Songs like “The Boys Are Back in Town” and “The Cowboy Song,” though not necessarily Irish-sounding, still boasted strong narratives – a very Irish trait. He helped burst open the door for the likes of U2. Sadly, the fast living caught up with Lynott, and this “father of Irish rock” (from his eulogy) died in January 1996 of liver failure.

If Lynott dipped his toe into the rock-meets-trad waters, then Horslips plunged right in. “It was glam-rock fused with Irish ceili. But it all made sense,” says Pat McCabe. Horslips used traditional Irish melodies to underpin epic tunes like “Dearg Doom” and “King of the Fairies.” Slagged by traditionalists, Horslips presaged electrified everything, and played those trad melodies with rock and roll swagger, before calling it a day in 1980.

But in the seventies, the advances of the likes of Rory and Lizzy and Horslips were undermined by the Danas and the Gilbert O’Sullivans, clogging the airwaves with their aural cotton candy. The Irish music scene was also undermined in a more overtly evil way — the 1975 massacre of the Miami Showband near Belfast discouraged UK and US rock bands from touring Ireland, north and south, for years to come.

There was a second explosion – a good explosion – in late 70s Ireland.

Groups like the Undertones (“I wanna hold her, wanna hold her tight/get teenage kicks right through the night”), from Derry, and Belfast’s Stiff Little Fingers (“Tin Soldiers,” “Alternative Ulster”) were influenced by the Sex Pistols and the Clash across the Irish Sea, and used punk as a springboard to rail about their own lives.

In Dublin, a scene began to coalesce around Jim Sheridan’s Project Arts Centre in Temple Bar. Groups like Gavin Friday’s Virgin Prunes and Philip Chevron’s Radiators from Space (pay attention to these mad clips), who couldn’t get gigs anywhere else, played loose, multi-media shows in the ramshackle building. Bob Geldof’s Boom-town Rats played sneering tours of Irish music halls, winning converts with snotty songs like “Rat Trap.”

Another band sprang from that scene. Four school mates made a new noise with their impassioned, geometric songs. Calling themselves U2 (“you too”), Paul Hewson (Bono Vox meaning “good voice,” later shortened to just Bono), Dave Evans (dubbed the Edge, for his sharp features), Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen turned the music world – Ireland and elsewhere – on its collective ear.

Geldof, not particularly known for his altruism, shone a light on the plight of Ethiopia’s starving by calling on his friends to perform “Do They Know It’s Christmas” (Bono: “Ya wrote a hymn there Bob, didn’t ya?” Geldof: “Fook off…”) and later, “Live Aid,” the transatlantic concert broadcast live to the world from Philadelphia and London.

Bono seized the moment for U2. “I thought it was a botched attempt at creating a moment,” says the Edge of the band’s performance. But Bono had the savvy to realize that the Live Aid concert was a show tailored for the television audience. When he dove into the crowd, Bono smashed the barrier between band and fan, and sealed U2’s meteoric ascent.

Bono seized the moment for U2. “I thought it was a botched attempt at creating a moment,” says the Edge of the band’s performance. But Bono had the savvy to realize that the Live Aid concert was a show tailored for the television audience. When he dove into the crowd, Bono smashed the barrier between band and fan, and sealed U2’s meteoric ascent.

U2 may have broken down the door (“U2 was the watershed. After them, anything was possible” – Paul Brady), but scores of quality artists of all genres walked right through it. Clannad had a worldwide hit with “Harry’s Game,” an ethereal burst of dreamy mouth music. Mary Black melded her Irish influences with a keen pop sensibility, as evidenced by “No Frontiers.” Enya left the family group, taking Clannad’s new age baton on a solo run, and has since sold millions of albums worldwide – and enticed scores to visit Ireland – with her otherworldly flutters and chants.

Singer-songwriters like Paul Brady – who’s penned songs that have been Grammy winners for the likes of Bonnie Raitt and Tina Turner – and Christy Moore (“Ordinary Man,” “Ride On”) continued the Irish bardic tradition, but also gave it a modern bent. And Donal Lunny, who got started with the foppish folk trio Emmett Spiceland, gave the traditional form a new jolt with each successive band he formed: Planxty, Moving Hearts, Coolfin.

From London, the Shane-MacGowan/ Philip Chevron led Pogues sang magnificent punk songs of emigration and alienation – all with Irish-sounding melodies.

And then came the anti-Dana. Bald-headed and stunning-looking, the video-friendly Sinead O’Connor sang songs that were a riot of Irish roots, rock, reggae, and bile. She captivated and alienated, always on her own terms.

Later the Cranberries, also fronted by a strong woman, Dolores O’Riordan, would claim their piece of the pie with harrowing tunes like “Zombie” and “Linger.”

So what’s the future of Irish pop music? Despite a recent lull – remember the “raggle taggle” movement, and more recently, Westlife? – From a Whisper’s producers are bullish. The film’s coda is a montage, showing Ash, Divine Comedy (“If I weren’t from Ireland, I think I’d look at things in an entirely different and much more bland way. In a way, I almost enjoy the completely buggered up psyche of Ireland.” – Divine Comedy’s Neil Hannon), Afro-Celt Sound System, even the Corrs, in their airbrushed way, carrying the banner into the 21st century.

So will there be another global phenomenon like U2? Probably not. The world’s a much smaller place due to TV and the Internet, and the notion of a rock band from Ireland isn’t all that exotic anymore.

But there won’t be an island full of Elvis imitators, either. And that’s a very good thing. ♦

Leave a Reply