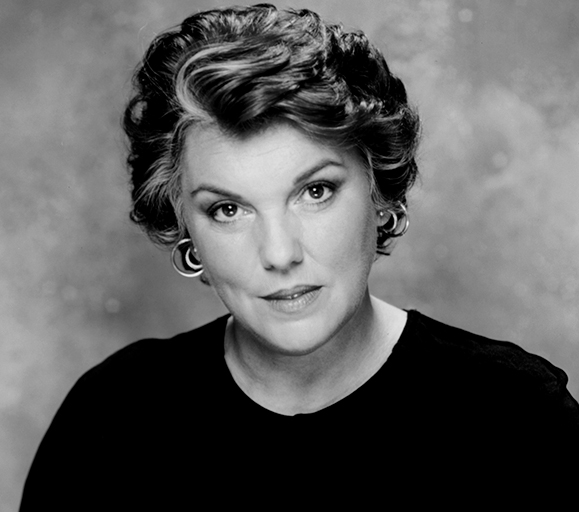

Tyne Daly, known to TV viewers as Mary Beth Lacey, takes on a new role in Dublin.

The character of Mary Beth Lacey is as firmly fixed in the collective televisual consciousness of the Irish as it is in Americans – perhaps even more so.

Yet it’s hard to imagine Tyne Daly, the person behind the persona, being swamped by autograph seekers in a Stateside mall; it wasa different story at Dublin’s Liffey Valley Centre in early May, as a leisurely shop turned into a love fest. By all accounts, Ms. Daly handled all and sundry with aplomb and autographs, and having met her recently, ahead of the opening of the Irish premiere of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children, I can affirm that aplomb is not the least of her virtues.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when, during the course of our meeting, the reality of Tyne Daly’s formidability sunk in. It’s the fault of the smile, you see. Seeing that smile in real life, in all its natural glory, initially makes it tough to see Daly for who she is. Mary Beth Lacey is instantaneously, almost unwillingly called to mind via the smile; one expects to meet the homey, soothing demeanor that established Lacey as the tough but good cop.

Not at all: Daly is sharp, smart, funny, poised and focussed. She is a Professional, very much with a capital P. There is no time for nonsense as she immediately gets busy with not only talking up the project that brought her to Ireland’s shores – Brecht’s 1941 play, transposed from the German playwright’s conceit of thirty years war involving Sweden and Germany into Ireland’s own North/South conflict – but with also seamlessly plugging her new series, Judging Amy, which kicks off this autumn on local network TV3.

This is not to say that the conversation was a cut-and-dried exposition of sound-bites. That’s not Daly’s inclination. She is a natural storyteller, and willingly shares the received history of her Irish roots: “The family myth is that the unmarried sisters of my great-grandfather – after he got rich in Wisconsin, cutting ice out of the rivers and shipping it all the way down the Mississippi River to New Orleans so that fancy gentlemen could have ice in their drinks – returned to Ireland to discover, as all Irishmen believed, that they had descended from kings.

“They came back from Macgillicuddy’s Reeks [mountains in Kerry] and County Tipperary saying they had gone from parish to parish and had all the records destroyed – they’d paid the priest to mark out all of the marriages, all of the deaths, all of the births, because they had discovered we had descended from tavern keepers and lowlifes.

“Then they locked their little lipless mouths and died disappointed behind lace curtains in Daly City, Iowa.

“Now, how much of that is true I haven’t the faintest idea. I don’t care. It’s a nice story.”

In contrast, the tale that Brecht tells is far from nice: Mother Courage is the quintessential chancer, who peddles her wares to any and all soldiers, no matter their side of the thirty years conflict. Her famous wagon must be kept rolling, and her three children, despite her love for them, eventually become little more than merchandise. She is both victim and villain, and as she manipulates and barters her way through her existence, in typical Brechtian fashion, the audience’s emotions are manipulated as well.

The practice of reframing classical theater pieces to reflect our modern times is not unusual – nor is it always safe. There is always the danger of far too facile a rendering of events, of hooking onto a set of superficial problems that seem to attach the old play to new times, and calling it a revision. However, the transposition of events to reflect the internal conflict on the island of Ireland is truly appropriate, and the play may actually allow the themes – of greed, self-determination, self-centeredness, survival – to apply themselves to a conflict that is often simplistically reduced to a war of religion.

“Oh yeah, gotta love that – it’s especially nice when you pretend it’s about God – `My God’s better than your God.’ I had a conversation last spring when I went up to Belfast. I’d never been to Belfast before, and I was talking with a woman who was working with children in theater and music as a way to bridge divides, and we had a conversation about government forms you had to fill out. I was telling her it would be really interesting if our government put an additional box on those lists, after Caucasian, Negro, Asian Pacific, that said `Human.’ Just to see how many people would choose that category.

“And the woman in Belfast said to me, `Well, you see, the question here is not how do you perceive yourself – as a Catholic or Protestant – but how you are perceived.'” Daly whistles in admiration. “Very interesting question! It’s not about your own feeling about yourself, it’s about, what are the neighbors saying. I thought it was fascinating!”

It is clear that Daly finds much of what surrounds her fascinating, in the way that the best actors among us are always looking to the world in order to learn about myriad experiences and reflect it back to an audience. She’s not too concerned about whether or not, as an outsider, she can literally translate the experience of living with The Troubles into her performance. “It may be to my advantage, as an American actor coming in, that I don’t understand all of the ins and outs of the endless Irish conflicts, because Mother Courage couldn’t care less. She is entirely involved in her own gain, and in getting herself and her children through. I don’t think she trucks much with the political ups and downs. All of that is framed around the experience of the woman herself. She’s a trader and an entirely self-serving opportunist. Whether or not she can understand all of that is not necessary to be able to accomplish the role.”

It is tempting at this juncture to attempt to unpack all the Brechtian baggage that comes along with any of the celebrated German playwright’s work. Almost exclusively embraced – some would argue, overshadowed — by academics worldwide, it is sometimes difficult to imagine that a night of Bertolt will be an enjoyable night out at the theater. Daly insists that playwright and German scholar Joe O’Byrne’s new translation is a real gem. “He’s managed a very hearty humor in it that was kind of removed from the play by certain other translators. Sometimes this play is approached as an operatic set piece. There’s a lot of theory around famous plays and about how they’re meant to be approached – none of which I’ve paid any attention to at all, because my job is to experience it as a brand new piece.”

Warmed to the subject, she continues. “The first obligation is to entertain, delight, amuse, confuse. What they’re thinking on the way home is not for us to dictate. It’s a communication. I send something out and every individual member of the audience has to communicate back about What they thought. I try not to involve myself in manipulating what they’re going to experience. I have to put my self in the imaginary circumstances and play validly there.”

She Pauses, and smiles that smile. “My responsibility is to the audience. They’ve got to come in and have a good evening of theatre. That’s what we promised them when they put down their money. If we bore them to death or lecture them…that’s not what I do it for.” ♦

Leave a Reply