I had almost a worm’s-eye view of Bloody Sunday. I was working as a junior TV journalist covering a protest march through Derry on January 30, 1972, and like every other observer I was dumbfounded when the British Parachute Regiment opened fire on the protestors. I had just maneuvered my way over a low barricade of rubble when the shots rang out, and I flung myself on the ground, tasting asphalt for the first time. The firing lasted several minutes – killing unarmed civilians, though I didn’t know that at the time. I saw and heard soldiers firing but couldn’t see anyone being hit. When a break seemed to come I got up and ran out of the danger area. The death toll turned out to be thirteen that day, and a fourteenth man died of his wounds later.

Twenty-nine years later, I was back in Derry. And I was back in a weird replication of the scene – thanks to digital technology. I was giving evidence to the current judicial inquiry into the massacre, and at an attorney’s direction I was inserting myself into a “virtual reality” recreation of the killing field.

The real location in Derry’s Bogside has changed almost beyond recognition over the years through demolition, reconstruction and landscaping, but with my finger on a computer’s touch-sensitive screen I was able to place myself back near that rubble barricade. An entire and eerily convincing panorama wheeled 360 degrees around me…the northern part of Rossville Street from where the paratroopers began shooting…the Glenfada Park gable-end to where 18-year-old Michael Kelly was carried with a gaping stomach wound and died…the southern end of Rossville Street, with its famous “Free Derry” daubing…round finally to the exact points where four more young men turned out to have been killed on my side of the barricade. Inevitably my mind hurtled back to the outrage, terror and panic I felt that cold afternoon, and I struggled to recall the events calmly.

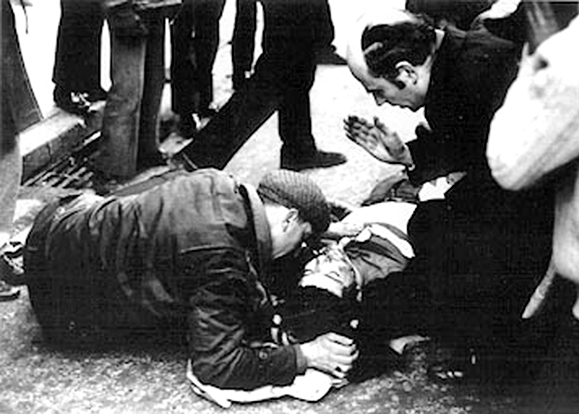

My testimony was followed by more intense images. When it was Bishop Edward Daly’s turn in the witness-box, all the screens that are scattered throughout the inquiry chamber and public gallery pulsed with moving pictures, relayed also to private rooms where daily the families of the dead gather to watch the proceedings. Old news footage, that is now iconized, showed a young Father Daly advancing in a kind of crouching walk, waving his bloodied white handkerchief, trying to gain passage for a fatally wounded youth, 17-year-old Jackie Duddy, being carried behind him. The Bishop’s quiet sadness in the witness-box, and his flashes of anger, brought a fresh human poignancy to the electronic visuals.

The inquiry’s high-tech imagery is just one aspect of a vast and complex operation. It takes place, ironically, in the converted council-room of Derry’s once corrupt and gerrymandered Guildhall, and since being mandated by Tony Blair in January 1998, inquiry staff have been scouring four continents for material witnesses – like myself, now living in New York. It has cost well over $25 million in public money so far, and the meter is still ticking, for hearings are expected to go on for another two years.

The effort and evident rigor being applied contrast sharply with how I recall the previous inquiry, conducted in the weeks immediately following Bloody Sunday by Lord Widgery, who in effect whitewashed the British Army. Widgery left unproven allegations in the air that the dead had somehow been a threat to the soldiers – with nail-bombs, perhaps, or concealed guns hastily removed after their deaths. For that inquiry, no attempt was made to investigate preparations made ahead of the fateful day by the different parties involved, least of all by the Army, nor was any evidence taken from the fourteen people injured (it was deemed not relevant to the deaths).

One of the earliest challenges to Widgery was transatlantic, coming from an International League for Human Rights observer, Samuel Dash, the American lawyer and academic who was much later to become known as ethics counselor to Whitewater Special Prosecutor Kenneth Starr. Professor Dash summed up many jurists’ objections to Widgery in the stark title of his critique: “Justice Denied.”

My own appearance before Widgery in 1972 was marked by haranguing from the Army’s lawyer:

Attorney: “The soldiers who were firing were NOT firing in your direction at all, were they?”

Witness: “They were firing down Rossville Street, yes.”

Attorney: “Why did you look up [at the high-rise flats] when you told my learned friend that at all times the rifles were held parallel to the ground, and not facing upwards at all?”

Witness: “I was there for some time. I was looking around me in all directions.”

My cross-examination 29 years later was at least courteous. The attorney acting for 440 soldiers who were on duty on Bloody Sunday mainly questioned the reliability of recollections like mine. I had perhaps unwisely written the previous week in The New York Times about the malleability of such memories when they are formed under hectic and traumatic conditions, and then frayed by the passing of time. “In an article you have described yourself as an unreliable witness,” the lawyer asserted. Picking up on my admitted uncertainty about the headgear of a particular soldier (was it a beret or a helmet?) he asked: “Do you believe it is possible, out of fear or for any other reason, to make similar mistakes over things you may have heard or not heard?” I could only reply: “I am sure all of us in this room would accept that, yes.”

The inquiry chairman, Lord Saville, and one of his co-judges, William Hoyt of Canada, stepped in to suggest that my visual recall may not have been as confused as I feared, and that some photographs showed both helmeted and beret-wearing soldiers in my vicinity. “I want to reassure you about your memory,” said Hoyt.

The inquiry’s leading attorney was at pains to draw out my testimony in detail. Like others before him he pressed me on whether I had heard or seen anything to suggest that the Army was coming under fire or under threat from any other weapon, like a bomb. The local TV station summarized my responses that night: “A journalist who covered the march which became Bloody Sunday said he could see nothing to justify the British Army shooting he witnessed from close range.”

[At the time of writing, the inquiry was being stymied by government gag orders which effectively prevented open investigation of some extraordinary leaked “evidence” from anonymous British Intelligence sources. These accused the IRA of having been present with firearms on the day, and of having been the first to fire.]

Summoning up the grim day’s memories was not limited, of course, to the inquiry chamber. I spent a week back in Derry, and, unsurprisingly, many of the people I came across in the city’s close neighborhoods had also been there on Bloody Sunday. A sudden, strange kinship would develop with each encounter. “Where were you? Sure, you must have been just 30 yards from me!” and so on, many times over. Some of us turned out to share an onerous sense of having unaccountably – even somehow unjustifiably – escaped while others died. “Survivor guilt” was a phrase that hadn’t occurred to me until it was voiced by the author Don Mullan – who was fifteen at the time and had been (we figured) about 25 yards from me when the shooting started. Another fellow-witness, Terence McClements, who was seventeen at the time, told the inquiry: “My instinct for self-preservation took over and I ran. I’ve felt guilty that a fella I knew, two feet from my shoulder, was shot – and why was I not shot.”

Others I met talked of wishing they could have done something for the victims. I myself didn’t even know if anyone around me had been hit – everyone seemed to be lying prone when I eventually got up and ran. I couldn’t tell whether they were hurt, or just being cautious as I had been. One man (I’ll call him Robert) had seen all too clearly one death, that of 22-year-old Jim Wray. Although Robert had given lawyers a written statement, he was feeling conflicted about testifying in the chamber. He shared many Derry people’s long-term distrust of the British authorities and saw no persuasive reason to believe Saville would be any better than Widgery. And, he confessed, he was simply nervous of standing up in public and drawing attention to himself. “I live here,” he said, “and this is a small community.” He was leery, too, about being cross-examined.

Before I went to the Guildhall, Robert and I talked of the terror and confusion we had each felt as young men. I had been 23, on what I thought was a routine reporting assignment; he had been in his teens, out for the day and excitedly stoning the troops. At about 4:15 that Sunday afternoon both our lives had (we agreed, from the vantage-point of 29 years’ hindsight) changed unutterably in some way. Robert went on to hear the radio coverage of my testimony while he drove through modern-day Bogside and he resolved then, he told me later, to give his evidence in person. “You came to give evidence for yourself,” he said. “But you also helped me decide what to do. I’m going to just stand up and tell them exactly what I saw.”

Ahead of my appointed day on the stand I had wanted, if I could, to maintain my role as a dispassionate, purely journalistic observer, so I was careful not to talk with families of the dead. When I did finally meet some of them afterwards, they were full of dignity and courtesy, even thanking me for coming and testifying. (I was awkward with them. — I did not quite know how to answer their thanks.) With a few, there was an inner fury evident alongside the gentle manners, occasionally, some barely contained wildness of emotion.

John, the elder brother of 19-year-old Willie Nash who was killed at the barricade, had also been there on Bloody Sunday – even though he had been married only the previous day. Now a man in his fifties, his hands shook as he spoke of stress and ill-health dogging his entire family ever since 1972. Another victim’s relative spoke of living today on medication, and said she would have wanted to spend longer talking with me, but her “nerves couldn’t really stand it.”

A lot rides on the lengthy legal process now unfolding in Derry’s Guildhall. Tony Blair, we can hope, obviously wants a clear assessment of what happened on January 30, 1972 which is different from Widgery’s “findings.” Why else hold the new inquiry? The British Army wants a damage-limitation exercise, at the least. Much of Northern Ireland’s nationalist-minded community wants someone to pay, or at least to be clearly blamed. For the citizens of Derry the daily procession of witnesses brings in its wake pain, horror, anger, bafflement…and who can know what else? But one family member simply said to me – and his tone precluded the slightest hint of any other agenda – “However uncomfortable we might find it, we just want the full truth to be told.” ♦

Leave a Reply