Paul Brady

Oh What A World

Compass Records

Let’s all ponder Paul Brady’s career for a moment. The man has written songs that have been recorded by the likes of Tina Turner, Joe Cocker, and Cher. He’s co-written with Roseanne Cash, Beth Nielsen-Chapman, and Curtis Stigers. “Luck of the Draw,” as recorded by Bonnie Raitt, netted a Grammy in 1991. His own work – listen to “The Island,” 1985’s peace anthem – is consistently fresh, endearing, and honest. Yet Paul Brady hasn’t had wide commercial success. Oh What A World, his latest Compass Records release, won’t change that.

Why?

The songs are too good, that’s why. They’re too literate, too complex, too varied, too subtle.

Take for instance “Travelin’ Wreck.” Over a chunky blues guitar riff, Brady sings “Rusted wreck by the roadside/And it ain’t goin’ nowhere/Too much like my life/And I wanna get outta here.” It’s a moment of unabashed self-expression, of throwing off life’s burdens. It’s bright, but there’s darkness, too. Not exactly Britney stuff, that.

That’s where Brady lives: in that gray area where the heart makes the leap, but is still wary of the vulnerability that might result. Songs like the softly grooving “Sea of Love,” and “Minutes Away, Miles Apart,” with its pedal steel swells, just underscore that ache. “I’m tumbling down,” he sings, and we tumble along with him. His voice is rough-hewn and golden, giving Oh What A World a comfortable, rainy day feel.

Look, no matter how Oh What A World fares in the charts, it won’t change Paul Brady’s approach to his work. He’ll still toil in his Dublin digital home studio, churn out fantastic songs, and collaborate with the best of the established and the new-coming songwriter alike. But wouldn’t it be cool if someone like Britney or J-Lo handed him the little golden gramophone one of these years?

David O’Rourke & Lewis Nash’s Celtic Jazz Collective

Aislinn (A Vision)

Mapleshade Records

After a gig they played together at the 1998 Cork Jazz Festival, drummer Lewis Nash – whose credits include playing with Oscar Peterson, Betty Carter, and Ray Brown – quizzed Dublin-born guitarist David O’Rourke about the music of Turlough O’Carolan. Nash had bought a CD of the blind 16th-century Irish harpist/ composer’s works earlier that week, and was intrigued by the melodies.

O’Rourke had always harbored a desire to meld the swing and rhythmic sophistication of jazz with the melodies he had learned as a youth. O’Rourke turned Nash on to O’Carolan and other Irish music, and the two set out on a path to combine these two improvisational traditions.

The result is Aislinn (A Vision). O’Rourke and Nash have assembled a band comprised of great musicians from the jazz and Irish music worlds, and they work through a set of fifteen songs with energy and panache. The album was recorded in live takes on vintage analog equipment, giving the music a warm, glowy feel.

Standouts include the gently grooving “Belfast Hornpipe,” “The Kid on the Mountain,” which evokes Miles Davis’ arrangements on “Kind of Blue,” and the beautiful “Beannaigh Sinn A Athair/An Pheadar,” two Sean O’Riada melodies that showcase O’Rourke’s deft guitar skills. And pay special attention to Nash’s stick work on both takes of “The Maid Behind the Bar/The Woman of the House,” on which he answers the ex-Bothy Band uilleann piper Paddy Keenan’s phrasing with incredibly nuanced drum conversations of his own.

The Celtic Jazz Collective is stylish, sophisticated, and most importantly, swinging. This album is a must-have for jazz buffs who wish to explore Irish music, for Irish music aficionados looking for a toe-hold onto jazz…ah, flip it: it’s a must-have, period.

Pat McGuire

Love Songs For Astronauts

Inverin Records

While with the New York-based band Speir Mór, Pat McGuire drew considerable interest and loyal fan fervor with that band’s melding of acoustic folk, Irish fiddle music, Cajun, classical, and electronica.

But the centerpiece was McGuire’s voice: a warm, resonant instrument which made Speir Mór’s songs of yearning and loss soar. Speir Mór is no more, but McGuire continues on as a solo artist. He’s just released Love Songs for Astronauts, on New Jersey-based Inverin Records.

The songs are more pop-based and radio-ready than his previous work: “Two Treble Zero” and “Don’t U Know I Want U” wouldn’t be out of place on alternative stations.

But the album’s emotional high point is “I Hate the Lies,” a vitriolic nursery-rhyme rant condemning corporate and media hypocrisy. Co-producers Vinny DiLeo and Sharkey McEwen create sharp, edgy soundscapes for McGuire’s songwriting.

If McGuire had an Achilles heel, it was that he would occasionally try to out-muscle some of the syllables with his strong voice, lessening the song’s natural drama. That’s not the case on Love Songs for Astronauts. McGuire has matured as a vocalist, wise enough to conserve his power for when it’s most relevant, trusting DiLeo, McEwen and company to help create the drama, too. Love Songs for Astronauts is an intriguing, special piece of work from a singer/songwriter who deserves broader attention.

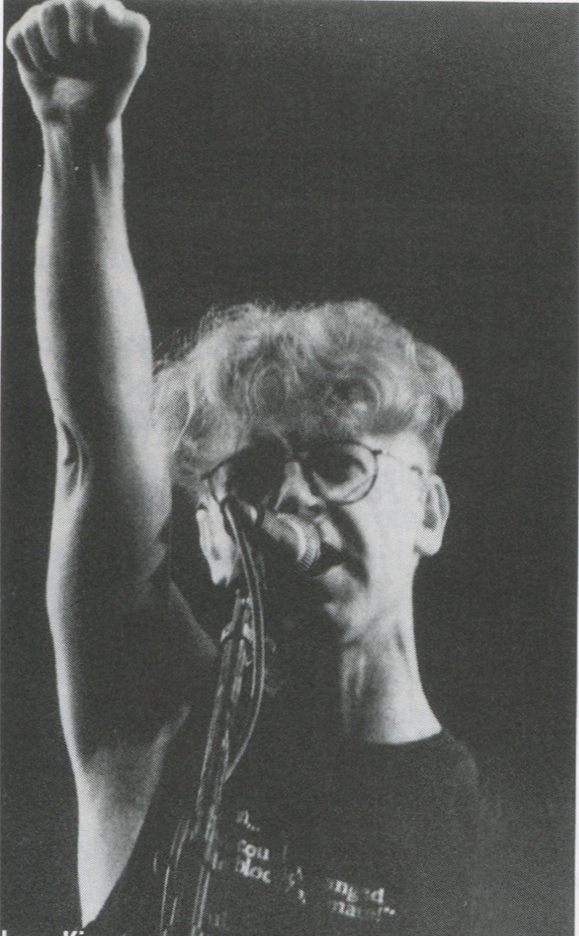

Larry Kirwan

Kilroy Was Here

Gadfly Records

As leader of Black 47, Larry Kirwan writes and sings broad, powerful songs of struggle and change, laughter and loss. Just listen to “Maria’s Wedding” or “James Connolly” to hear what I’m talking about.

But on Kilroy Was Here, Kirwan’s first solo work, he looks deeper inward. Paring down the instrumentation to just a trap kit, upright bass, guitar, and the occasional fiddle or horn – remember, Black 47’s arrangements are big and brassy – Kirwan gets down to the business of looking beneath the rocks.

“Molly,” is a tender love song to James Joyce’s Molly Bloom, marked by a swelling trumpet fanfare. “Fatima,” a tale of a family separated by the Atlantic Ocean, which seems to grow wider by the day, is spooky and harrowing. And you’ll laugh aloud at Malachy McCourt’s cameo on “History of Ireland, Part I,” on which he plays the part of a blustery English schoolmaster who spouts the Anglo-slanted history lessons that weren’t uncommon in Irish schools.

Kilroy Was Here has an improvisational, almost jazzy feel: recorded in minimal takes, the music bends, dips, groans – but never breaks. Larry Kirwan allows us an impressionistic glimpse into his songwriting process, and the view is at once poignant and powerful.

The Prodigals

Dreaming in Hell’s Kitchen

Grab Entertainment

The Prodigals’ sound is born of countless gigs – this airtight New York-based quartet criss-crosses the country extensively, bringing their distinctive brand of jig-punk-funk to new audiences each night.

That tightness is evident on Dreaming in Hell’s Kitchen. Drummer Brian Tracey and bassist Andrew Harkin provide the rock-solid foundation; accordionist Gregory Grene and singer/guitarist Ray Kelly spin catchy melodic lines above.

The songs are grooving and danceable, from the lilting “Morning After” to the driving “Paddy’s Heaven” and “Jackie Hall.” “Last Night As I Lay Dreaming” takes the theme of the traditional “Spancil Hill” and sets it on its funky ear. And bassheads will enjoy Harkin’s jaunty, bubbling solo on “Baggot Street” – he was recently pegged by Bass Player magazine as an up-and-comer.

If you haven’t seen The Prodigals, run to a bar or a nightclub near you when they’re in your town. Until then, pick up Dreaming in Hell’s Kitchen – this sharp collection of songs evokes the band’s live sound with muscle and gusto.

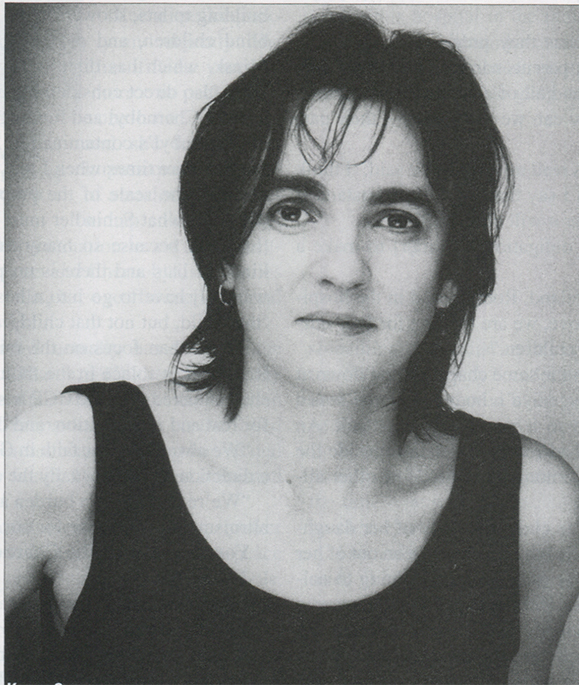

Karan Casey

The Winds Begin to Sing

Shanachie Records

Karan Casey was the voice of Solas, the Irish neo-trad group known for its innovative phrasing and rhythmic drive, for five years.

She left to pursue her own career, and to devote more time to motherhood. But The Winds Begin to Sing is no dalliance, no part-time affair. Casey owns the considerable gift of being able to inhabit a song, even an ancient one, and make it her own, with her crystalline voice and sean nos-influenced quaver.

She’s also a jazz buff, citing Billie Holiday, Nina Simone and Ella Fitzgerald as influences. That sense of phrasing, of singing before or behind the beat, is evident throughout. “Who Put the Blood” and “Buile Mo Chroi” are percussive and beguiling. “Where Are You Tonight I Wonder,” with its simple, plaintive piano figure, is deceptively soulful. Her band, led by husband and concertina player Niall Vallelly (who, incidentally, is a featured player in the Celtic Jazz Collective) creates arrangements that are thoughtful and spare.

The high point of The Winds Begin to Sing may well be Casey’s take on “Strange Fruit,” the Lewis Allen-penned song made famous by Billie Holiday.

The lynching saga haunts, as Casey straightforwardly sings the awful tale over an almost imperceptible drone. Chilling.

There’s an overriding feeling of air, of space, of understatement on The Winds Begin To Sing. Karan Casey is an important artist; a young woman wise enough to allow her music to float and soar. The only way is up. ♦

Leave a Reply