April 26, 1986: At 1:23 AM an explosion in reactor number four of the Chernobyl nuclear plant spewed 190 tons of radioactive material into the atmosphere, creating a cloud that traveled over northern Ukraine, into Belarus and eastern Russia. In the weeks following the explosion, excessive levels of radiation were recorded in northern Scandinavia, Wales, Ireland, Greece and parts of Alaska. In fact, each corner of the world received at least a minor dusting of radiation from that single explosion. Shortly afterwards, thousands of Ukrainian and Belarussian citizens were stricken with symptoms of acute radiation sickness, including vomiting, hair loss and severe rashes. Over 600,000 people were conscripted from throughout the then-Soviet Union to cleanup after the accident. Referred to as bio-robots, they were sent in with minimal protection after the mechanical robots ceased to function in the highly radioactive environment. Thirteen thousand of these men died in the year following the accident and tens of thousands have died since, while thousands more are permanently disabled. And that is only one small strand in the horror that is Chernobyl’s continuing legacy.

Fifteen years later one would hope to be able to forget Chernobyl and place faith in the Earth’s and humanity’s abilities to heal, to recover. But the facts won’t bear this out. Today, the children who absorbed the radiation in 1986 are having children, and in a tragic twist it has been determined that radiation passes through the placenta, into the fetus. It is estimated that ninety percent of the Belarussian gene pool suffer the effects of Chernobyl – that’s ninety percent of the children. The victims of Chernobyl are still being born – born with thyroid cancer, tumors, malformations, and congenital heart ailments. Doctors in Belarus have coined the term “Chernobyl AIDS” to describe illnesses springing from the damage to the immune system from radiation.

“This is truly a demographic disaster,” insists Adi Roche, executive director of the Irish-based Chernobyl Children’s Project. “This hasn’t peaked. We have hardly even reached the threshold of its capacity to destroy life because of the effects on the DNA, because we know radiation penetrates the placenta and affects the unborn fetus. So it’s passing from generation to generation.”

The Chernobyl Children’s Project is the first and largest Irish charity working to relieve the suffering caused by the Chernobyl accident. Founded by Roche in 1991, it has received a great deal of support from one Ali Hewson, better known as Bono’s wife. Thanks to their efforts, Ireland, a non-nuclear country, has emerged as the leading nation in dealing with this disaster.

It’s St. Patrick’s Day week and Roche is in New York City to drum up support for “Black Wind/White Land: Living with Chernobyl,” CCP’s multimedia art exhibition that tells the stories of the people who still live under the shadow of Chernobyl. Hosted by the United Nations, the exhibition opens on April 26 (fifteen years to the day since the accident) and run until May 27.

The exhibition presents Roche and the rest of CCP with a unique opportunity to bring the truth about Chernobyl to an international level. They frankly admit that they face an uphill battle against the world’s ignorance about the aftermath of Chernobyl and the long-term effects of radiation in general.

“Chernobyl didn’t finish in 1986,” Roche maintains. “That was really only the beginning, because three percent of the radioactivity was released at the time of the accident. The rest of it is still inside and they covered the reactor with this big cement sarcophagus. There are a thousand square meters of holes in it – some of them are big enough to drive a car through and they’re leaking radiation every single day.

“Chernobyl has been relegated to history,” she continues, “because of ignorance and the lack of understanding about what radiation does.

“I suppose in a way we were all lulled into a false sense of security after the accident. There was a huge, smooth P.R. job by the Soviet Union, as it was then. They actually passed forty pieces of legislation to ensure that the truth would never be known. They altered the internationally accepted levels of radioactivity and these laws are still in practice. If you’re a doctor and someone dies in your care from radiation related illness, you cannot put it on the death certificate because you will lose your job.

“Some of the key scientists that we work with are under house arrest or have been imprisoned. So it is very, very difficult. Our task is about breaking the silence, about telling the truth.”

In December 2000, the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was closed. Today the nuclear reactor sits at the center of a 30-kilometer exclusion zone. The contaminated region is as large as England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland combined. Ninety-nine percent of the land of Belarus – a non-nuclear country – has been contaminated enough to exceed internationally accepted levels. The nine million people living in this region have been exposed to more radiation than any population at any other time during the history of the atomic age, even the citizens of Hiroshima.

“All these years later, people aren’t supposed to give their children milk or any dairy products. They’re not supposed to have meat. They’re not supposed to have wild berries, which is part of their staple diet,” Roche points out.

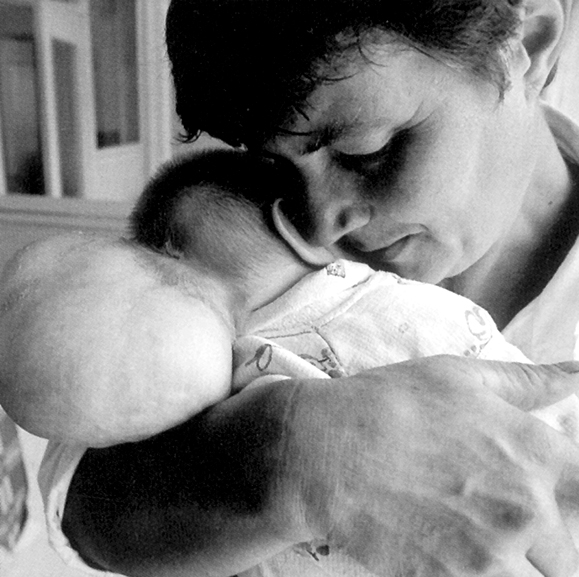

“I remember being with one mother who had a little child of about a year and a half and [the child’s] skin was like parchment – it was the color of death. I talked to the mother, and what she spoke about just broke my heart. She was carrying the guilt for the [illness] of her daughter, and I said, `Why are you carrying that? It’s not your fault. You didn’t make this incident happen, you can’t escape from radiation.’ And she said, `But I breastfed my daughter.’ The poison had passed through the breast milk. They have no access to other forms of baby food, and an awful lot of mothers were caught every way they went. No baby food and no breast milk.”

The world of Chernobyl is a world turned upside down, where silent, beautiful landscapes disguise the poison of radioactive elements that are purely man-made, where a mother’s attempts to provide for her child can ensure the child’s death, where resources, aid and money are so limited that sometimes the only way a mother can save the life of her child is to put him up for adoption.

“Every time a mother feeds her child she knows that she is poisoning her child. But she has absolutely no other option,” says Roche. The poor economies of the affected countries prevent uncontaminated food from being imported into the region, and also limit the scope of evacuations still taking place as the radiation zones spread through common traffic and radiation hot spots shift.

“One of the most poignant moments that I experienced there was working with the evacuees when they were being taken out of their towns and villages,” recalls Roche. “I remember being with one old woman who had survived the Second World War. She’d lost her husband and her brothers at the hands of Hitler. I asked what it was like for her leaving, and these are her exact words: `I’ve not only lost my home, my livestock, my farm. I have lost life. Chernobyl is like a stone in my heart, always heavy.'” This woman received the equivalent of five dollars in compensation for her family farm.

Roche speaks quickly and urgently. She has fifteen years of horror to pack into a one-hour interview and she has all the impassioned intensity of a zealot. She carries a map colored purple, red, orange and yellow, which charts radiation levels in the contaminated regions. On trips to Belarus and Chernobyl, she carries her own geiger counter. As she talks, her eyes frequently cloud with tears but never quite spill over.

Her involvement with Chernobyl actually has roots in the United States. “It was the 27th of March, 1978 that changed my life,” she recalls. “That was when a nuclear accident happened on Three Mile Island in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. My brother lived there [at the time] and my sister-in-law was expecting her second child. Out of that concern for my family I got involved in Ireland in the environmental movement.”

Her environmental work and campaign against nuclear power ultimately led her to work for world peace. She created a peace and justice program in Ireland’s primary and secondary schools, traveling the country for several years as a self-described “nomadic educator.” She describes this work as “teaching to create the mind of peace, because I honestly believe if war is made in the minds of men, so too can peace be made in the minds of men and women.”

One day she received a fax in her office from doctors in Belarus and the Ukraine. It read, “SOS Appeal: For God’s sake, help us to get the children out!”

“We didn’t even know what that meant but we acted at gut level and said we’d do it. We had no idea what it was about, what we were getting ourselves into. And now look at where we are ten years later. It’s quite awesome.”

Today the Chernobyl Children’s Project is divided into several programs. The Rest and Recuperation program takes children from Belarus and the Ukraine out of their contaminated environment for a summer holiday with a host family in Ireland. The program brings approximately 1,200 children to Ireland each summer. It’s more than just a vacation, the health benefits are quantifiable in real terms: for every four weeks a child spends outside of their contaminated environment, two years are added to his projected life-span.

The program also provides care for terminally ill children at the Paul Newman Barretstown Castle Centre in County Kildare and long-term care for children in state homes in Belarus and western Russia. CCP has even pioneered and brokered an adoption agreement between the countries of Ireland and Belarus, facilitating Irish families’ adoption of the children of Chernobyl. “We saw this as a human rights issue,” Roche maintains, “and our organization actually brokers for the Irish government, which is a unique thing and I feel so proud of that.”

Their second program is to provide medical supplies and humanitarian aid to hospitals and orphanages in these stricken regions. So far CCP has delivered over £18 million of aid and more than 120 ambulances.

The third program, organizing life-saving operations, was a natural extension of the previous two. And as with so much that happens with CCP, it was initiated by a child. Roche recalls, “I was in this hospital in the radiation zone and the kids were following us. They’d think you might give them a pen or you might have some candies, because candies are a big novelty over there. And out of this whole gang of kids this one voice shouted out something in Russian and there was silence. I said to the translator, `What did he say?’ and the translator started getting upset and then the doctor started blabbing in Russian. I said, `What’s happening, what has he said?’

“The translator looked down at the floor, because they are a proud people, and said – this boy, Vitaly, was nine-years-old at the time – he said, `Please take me to your country. I will die if you leave me here.’

“I turned to the doctor and asked, `What does he mean?’ and he said, `We have no medicine, no equipment. This boy suffers from a new condition called Chernobyl Heart. He’s had several heart attacks and strokes.’

“I remember being rooted to the ground and I recalled a feeling I’d had two years before in this home for abandoned babies. I remember holding a child, a boy, Yury, and I remember feeling his life draining out of his body. I don’t know whether he had hours or minutes, maybe a day, but no more than that. I remember wanting to fuse my life-blood into him, and I remember feeling overwhelmed by the sense of grief, of mourning – all of the children there knew they were dying. There was nothing I could do for this boy because it was too late. Even if I had medicine, it was too late for him.

“And here I was, two years later, being given another chance.”

There were no phones in the vicinity, but Roche was able to get a message to Mercy Hospital in Cork, asking them if they would treat the boy. They agreed.

When she informed Vitaly’s doctors, they asked, “But Adi, you remember his friend, Sasha? He has the same condition. Will you take him too?” She agreed. But then there was also five-year-old Artyom and a little girl, Evgeniya, who was critically ill, but doctors were unable to find a diagnosis for her.

It was Christmas week and Roche needed to find a way to get these children to Ireland. They were unable to fly on a normal airline because the high altitudes would have caused them to go into heart failure. So on Christmas Eve, Roche telephoned a millionaire in Iceland she had once met and asked if he would pilot his private plane to Chernobyl to get the kids out. He agreed.

About four days after Christmas they prepared to board the plane. “I still remember the four parents carrying their most precious beings – their children – and all of a sudden it dawned on me, what if these kids die? How can we carry that? – their parents weren’t coming with them.

“It was as if one of the mothers read my mind. She said, `I think I speak for all the parents when I say that we will understand if the next time we see our children it will be in coffins.’

“They released me from that obligation [in order] to make a miracle happen.”

On the night they arrived in Ireland, Roche stood in the hospital chapel and prayed, “Man Above, we are looking for four miracles, for the lives of these four children.”

Six weeks later Roche stood in the same chapel gazing down at a white coffin holding little Evgeniya’s body. She was seven years old when she succumbed to a massive heart attack. An autopsy revealed that the child had received radiation inside the womb and had been born with, among a multitude of other ailments, advanced osteoporosis.

“We brought the mother over to claim the body of her daughter. Can you imagine – this woman who has never been out of her village, never been in a car, never mind a plane, coming to collect the body of her daughter. Her husband couldn’t come because they didn’t have the money and we couldn’t get the money to him. The neighbors collected the money for her passport, which was $60.

“And she arrived. I’ll never forget the night in the funeral home. She took her daughter out of that coffin and examined her from the roots of her hair to the tips of her toes and keened and keened. I will never forget the sounds from that mother.

“She stood up the next day at the funeral ceremony and said she wanted to share a story: She’d had a dream, and in this dream she was in a strange hospital in a strange country and she was sitting in the hallway.

“Evgeniya came running down the corridor and [her mother] called out, `Evgeniya, what about your pain?’ Evgeniya spun around and said, `Mommy, there is no more pain.’

“The night she had the dream was the night Evgeniya died.

“I was always afraid to touch the death of Chernobyl,” Roche reflects, “because it was always easier to bring kids for rest and recuperation, but this little boy, Vitaly, directed us to take the risk.

“Not always does the miracle we ask for happen. I had asked God for four miracles [and] Evgeniya’s miracle was to be released, because from the second of her conception she was in crisis, even as a fetus.”

The three other miracles – Vitaly, Sasha and Artyom – survived their operations and return to Ireland every summer for rest, recuperation and medical check-ups.

In addition to these programs, CCP provides Chernobyl victims with long-term aid to improve living conditions, such as building toilets, showers and a laundry unit for an orphanage for blind children, and providing support for the TB Hospital in Minsk, which has directly resulted in the cure of 86 children. They also direct considerable efforts toward education about the truth of Chernobyl and funding ongoing research and monitoring of Chernobyl’s contamination.

“There are times when I feel that it’s just too big for us to handle, that the scale of the problem is just so enormous. I often [wonder] what Schindler must have felt like when he was doing [his] list, because so many times I have had to create similar kinds of lists and there is no power in that. It is a role I never want. [I] have to go into a hospital, into an institution and say, `that child, but not that child,’ and that just tears me up.”

Rather than focus on the millions of children she can’t help, Roche takes solace in the thousands she has helped, in the lives she has saved. To date CCP has brought 8,500 children to Ireland for rest and recuperation, and dozens of children for adoption.

“We always put our faith in God and let [ourselves] be carded in a direction, and it’s usually the children who give us the direction.

“We’re here to lift a burden and we do it, not so much from our altruism, but in a sense for our own salvation.” ♦

Leave a Reply