Gotcha. There was a craze afoot at the end of the last century — gosh, doesn’t that sound strange, especially since it was a mere couple of months ago — to list things. It seemed like everything — books, films, plays, albums, inventions, historical events — got categorized, ranked, compared, collated, crunched, and spat out…

The very notion of a “greatest Irish rock albums of the century/millennium/epoch” is a flawed and silly one — rock and roll didn’t come into being into the early fifties, and despite Van Morrison’s late-sixties trailblazing, Irish pop music didn’t really hit its stride until the eighties. (No, Dana’s “All Kinds of Everything” doesn’t count.)

So instead of a millennial summary of music, Irish America humbly offers up this collection — in no particular order — of essential Irish rock albums you should own.

The criteria? They had to be compelling listening, of course. But just as importantly, they had to push the envelope and cause the listener — and the pop world at large — to take notice of Ireland as a musical entity. There were some hard choices, of course: War or The Joshua Tree? The Lion and the Cobra or I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got? Astral Weeks or Moondance? Read on.

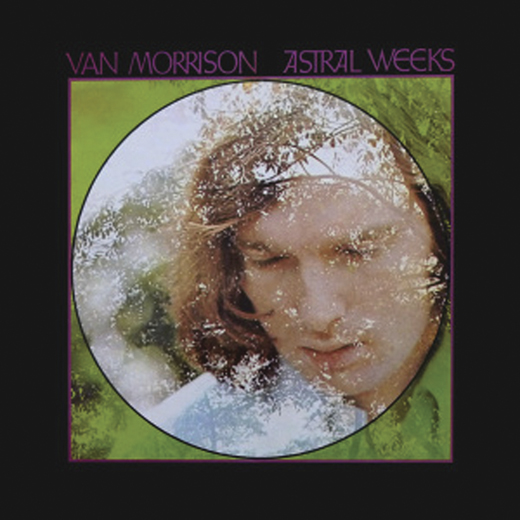

Van Morrison, Astral Weeks (1968)

He had made a name for himself with his band Them by singing snotty pop hits like “Gloria” and “Here Comes the Night.” But Astral Weeks was a fulfillment of Van Morrison’s musical vision, a vision made more astonishing by the fact that Morrison was still in his early twenties when he made this record.

Astral Weeks was everything Morrison’s earlier work wasn’t — lush, airy, hypnotic, spiritual. The album seems infused with equal parts Celtic myth and Delta blues. According to the jazz session players who played on the album, Morrison didn’t even instruct them on how to play the songs, instead trusting them to follow their musical instincts. The result is a loose, improvisational effort, witnessed by the loping swing of “Sweet Thing,” the bells-and-brash drive of “Ballerina,” or the jaunty harpsichord figure on “Cyprus Avenue.” Morrison’s voice is impassioned and higher than it is now — much like new wine ready to assume its vintage. Soon thereafter came the full-on jazz-rock of Moondance, but Astral Weeks presaged it with a beautiful, unlikely alchemy.

U2, War (1983)

That familiar, militant drum tattoo is by now beaten into our heads — “rat-tat-tat-tat-TAT-TAT, rat-tat-TAT, rat-tat-TAT.” Who had ever written a popular song about the North before? U2, four lads from Dublin, took on the thorny topic on War, the band’s third album. “How long/how long must we sing this song.?” sang Bono on “Sunday, Bloody Sunday,” and the world sang with him. Decidedly pacifist and vaguely Christian, Bono, along with guitarist The Edge, drummer Larry Mullen, and bassist Adam Clayton, called for peace and love amidst a blizzard of throbbing bass-lines, muscular drums, and jagged guitar figures. The songs were compelling — who could forget the loping, yearning “New Year’s Day,” the herky-jerk stomp of “Two Hearts Beat as One,” or the pleading “40,” based loosely on the Fortieth Psalm. War is a document of a band poised to break out — they did, of course, coming soon to a mega-stadium near you. Pay special attention to the tension and release of The Edge’s slide guitar solo on “Surrender” — it’s a gem.

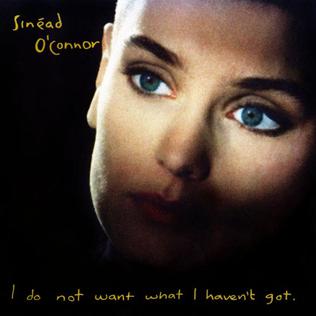

Sinead O’Connor, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got (1990)

It may have been the unusual look -the bald head, the huge piercing eyes — that first got Sinead O’Connor noticed. But it was the quality of her early work, first with 1987’s The Lion and the Cobra and then with I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, that put her on the musical map. I Do Not Want is a stunning, dramatic, angry effort. “I Am Stretched on Your Grave” runs that gamut of emotion — a detached, droning O’Connor laments her loss over a hip-hop drum loop, but that coldness turns to sheer fire at the entrance of the song’s maniacal fiddle solo. O’Connor steals Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” for herself much the way Aretha Franklin stole “Respect” from Otis Redding. Many call O’Connor preachy, but kudos to her on “Black Boys on Mopeds” — she rakes Thatcher-era racism over the coals. And is there a line in rock that better illustrates the pain of falling apart than “you used to hold my hand/when the plane took off,” from “Last Day of Our Acquaintance”?

Horslips, The Tain (1973)

What was this? A rock band playing electric versions of traditional Irish tunes? Sacrilege…

So what if Horslips was initially met with the same derision that Bob Dylan was when he turned his folk songs electric? The members of Horslips — Jim Lockhart (flute, whistle, vocals), Barry Devlin (bass, vocals), Johnny Fean (lead guitar), Charles O’Connor (fiddle, mandolin, vocals) and Eamon Carr (drams, vocals) had a vision — they would turn Irish music on its ear by turning on their amps. The purists hated it. But the kids loved it — revved up versions of “Silver Spear” and “Dearg Doom” are filled with bluster and fury. Horslips disbanded around 1980, but they were true originals. The members recently wrested back control of their music in the Irish courts; rumors are flying about a Horslips reunion this summer. And you want to talk about “concept” albums? The Tain was based on the Irish mythological cycle about the wars between Connacht and Ulster in approximately 500 B.C. Take that, Emerson Lake and Palmer.

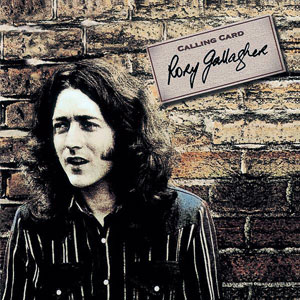

Rory Gallagher, Calling Card (1976)

He rivaled Clapton and Page as one of the world’s premier blues-rock guitarists — legend is, he even turned down an invitation to join The Rolling Stones. Rory Gallagher played — and lived — the blues on his own terms. Calling Card is his finest studio work. From the ferocious, minor-key funk of “Do You Read Me” to the plainrive slide guitar work on “Admit You Were Wrong” to the barrelhouse bluster of the title track, Gallagher proved he could paint in all shades of blue. Sadly, Gallagher died in 1995 from complications following liver transplant surgery. He left us all blue.

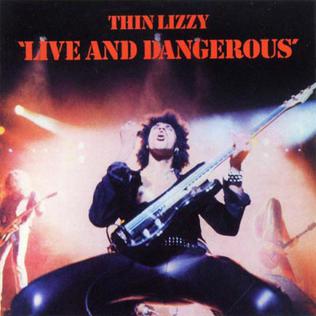

Thin Lizzy, Live and Dangerous (1978)

Live albums are iffy propositions — pale imitations of a group’s album cuts, usually assembled for a ‘greatest hits’ payday. But Thin Lizzy’s Live and Dangerous is an emphatic exception. Every song on this fine album throbs with fierce energy, from the opening sirens of “Jailbreak” to the pleading chores of “Don’t Believe a Word.” Phil Lynott’s songs dripped with working-class alienation. A black man in a white Ireland, Lynott looked different, dressed different, sang different, was different — he was also well ahead of his time. Sure, the twin-guitar lead thing may sound a little dated now, but damned if Lynott didn’t throw himself headlong into his music.

“Dancing in the Moonlight” skips with lovestruck giddiness, “The Cowboy Song” extols life on the range (made sweeter by the fact that Lynott, who was from inner-city Dublin, had never even been near the open range) and “Southbound” flat out rocks. One wonders what Lynott would be doing now had he not died at 35 from the health complications of a rock and roll lifestyle; it’s pretty safe to say he’d still be making brawny music. Live and Dangerous is that rarest of animals — a live album that captures a band’s true essence.

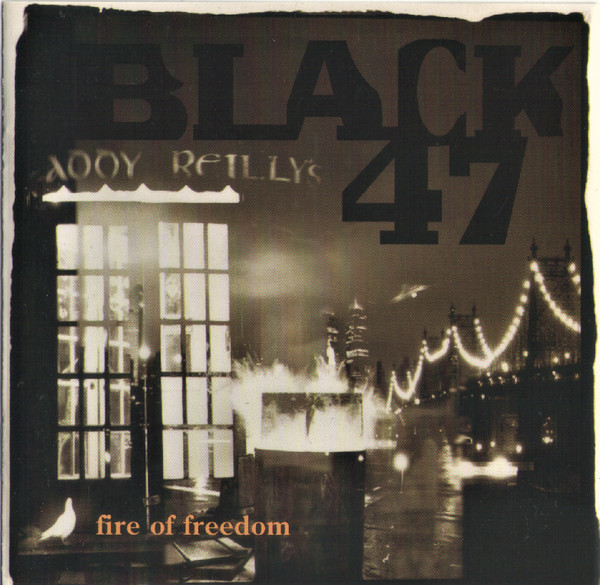

Black ’47, Fire of Freedom (1992)

When playwright Larry Kirwan and patrolman Chris Byrne conspired to create a band with a new sound a decade ago, even they had no idea what they would stumble upon.

This was not your father’s Irish music. Black 47 wrote funny, dramatic, empathetic songs that spoke to me “new” Irish in America — the nurse, the nanny working extra shifts as a waitress, the construction worker who would cash — and drink away — his paycheck at the bar. “Funky Ceili” was the hit — a tale of a ne’er-dowell who faced “castration/or a one-way ticket to New York” from his girlfriend’s father when he learned she was pregnant.

In fact, the entire album had one foot in Ireland, the other in Gotham — witness the Irish/Italian sparks of “Maria’s Wedding,” or the exasperation of “Livin’ in America.”

Here was a band willing to experiment with the rap, reggae and Latin sounds they heard on the streets of New York — yet they also drank deeply of their Irish roots. One listen to “Fanatic Heart” explains this band’ s importance.

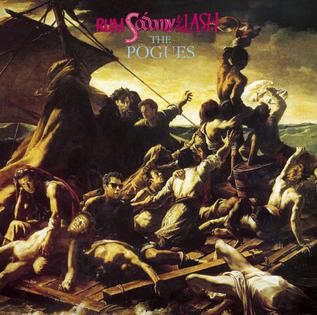

The Pogues, Rum Sodomy and the Lash (1985)

Rolling Stone magazine once called them “the musical equivalent of a pub crawl.” The Pogues, a motley brand of London-Irish fronted by a souse with painfully dreadful teeth, kept the punkrock flag flying in the eighties with their snarling brand of Celt-punk revelry. But the real heart of The Pogues music was Shane MacGowan’s songwriting — it was clever, it was tender, it was angry, it was insightful. Those skills are best shown off on the Elvis Costello-produced Rum Sodomy and the Lash. Personal tales of drink, love, sweaty sex, abandonment and loss abound -“They took you up to Midnight Mass/and left you in the lurch/ so you dropped a button in the plate/and spewed up in the church” sings MacGowan on “Sick Bed of Cuchulainn,” and you just know he did. “The Old Main Drag” tells a dark, strung-out tale of personal compromise. But the grimness is tempered by joyous songs like “Sally Maclennane” and “Navigator” — “they never drank water/ but whiskey by pints.” The band, led by whistle player Spider Stacey, whips out these songs like there’s no tomorrow — and that notion was entirely possible with the likes of MacGowan.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the April / May 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply