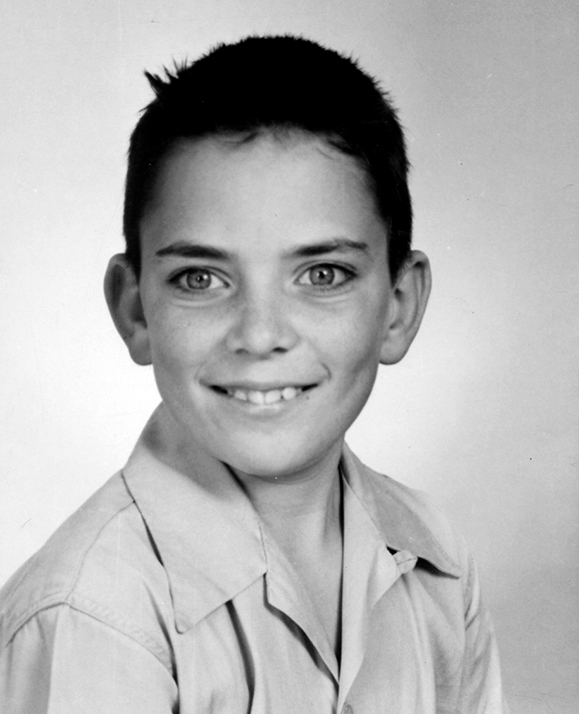

My grandfather, Denis A. Lyons, was my best friend and playmate. He used to spend many hours with me trying to support and mold my forming personality. As is the tradition among the Irish, he used stories to illustrate whichever point he was trying to make. He told me many, many stories but only one has remained with me in its entirety all these many years later. It must have been told to me sometime in 1952, when I was seven years old, two years before he died. It went something like this:

“Well, little Teddy, come here and climb on my lap. Do you know what N.I.N.A. means? You don’t? Well, thanks be to God that you haven’t had to know. I’m going to tell you a bit of family history. Your family’s history. This happened to me and had a direct impact on Grandma and your more and all three of your uncles.

“You see, I was back from the war. Not the war your daddy and mommy served in. No, the one before that. We called it the Great War then. Nobody had begun numbering them yet. Times for a veteran with a family were not especially good in Iowa. The Depression hadn’t hit yet but it was on its way even though we didn’t know nor suspect it.

“I was unemployed and trying desperately to find work. After all, your momma and uncles and grandma all had to eat and I had to keep the roof over our heads. Times weren’t easy, but we made do.

“Well, that’s where N.I.N.A. comes in. You see, I’d spy a sign in a window, `Help Wanted’ and I’d quicken my pace and hurry over to it. I would hope each time I’d see such a sign that this one might be the one that would lead me to a job and a chance to put some good food on the table for my wife and children. Then I’d get there and read it. Across the bottom of the sign would be those initials, `N.I.N.A.’ Little Teddy, those initials stood for the words No Irish Need Apply. I was unwelcome and unwanted, and as far as that store owner was concerned, it would be all right if I starved to death and took my family with me. That was not because I was a bad man or had committed an evil act, I was just Irish.

“Well, one day after walking through one small town in Iowa and then through the farmlands and into another small town and encountering nothing but `N.I.N.A.’, I was trudging home and feeling mighty low when I noticed a man in a peculiar getup ahead of me on the side of the road. He had a black, wide-brimmed hat and a full beard and these curlycues of hair on the sides of his head. He was wearing a black suit and had these little string things sticking out from the bottom of his vest. I never had seen the like! I remember thinking that at least, when I got home that night, I’d be able to weave a story about him and try and distract your momma and her brothers from the fact that all they’d be having would be milk toast again.

“As I drew near him, he looked up at me and smiled. You know, I believe that he was the first person that day to smile at me. It’s a small thing, a smile is, until nobody will give you one.

“Well, as I was saying, he smiled at me and then he said, `Boy, ya vant a job?’ [Grampa did the accent to underscore his story.] I told him `Yes, sir, I want a job.’ Then he asked me a question that went through my chest like a knife, `Boy, ya Irish?’ I tell you, little Teddy, I could have exploded. There were so many things I could have said, but I didn’t. So, anticipating the rejection which I was sure would follow, I said, `Yes, sir, I am Irish!’

“To my surprise, the man then smiled again at me and said, `Goot, ya come back tomorrow and I vant ya should dig me a trench. It should go vrom here to dere and it should be zo deep. See ya at eight o’clock sharp tomorrow.’ All my way home from there I doubt my feet really touched the ground. I’d found a job. Not a permanent one, to be sure, but a job nonetheless. We might be having milk toast tonight but tomorrow night we’d have maybe a bit of ground meat!

“The next day, I was there at a quarter of eight. I didn’t want to risk being late and seeing the job evaporate. True to his word, the gentleman was there in the same strange outfit and with the same accent, I had borrowed a shovel and a mattock. The gentleman showed me exactly where he wanted his trench dug and once more gave me the dimensions he desired.

“I marked out the area and began swinging the mattock. I dug all day and by the end of the day the trench was dug and it was one fine trench, even if it’s me saying so. I carefully finished the sides so that it did not look like it had been dug by someone in a hurry who didn’t care.

“The gentleman strode up to me as the shadows were lengthening and I was putting my jacket back on. He walked around the trench and looked it over carefully, nodding his head and making small approving noises. I was proud of my trench and it pleased me to see that he could appreciate the extra care I’d taken to make it a really well constructed trench.

“Well, I’m here to tell you, little Teddy, that he came up to me and stuck out his hand and said, `That is one fine trench you dug for me, boy.’ Then he paid me. Honest wages for honest work. My chest felt like it’d explode. It’d been a bit, you see, since I’d had any kind of job. I thanked him for the money and was about to walk home to your grandma and momma and uncles when the gentleman said to me, `Hey, boy, ya vant another job for tomorrow? Be back here at eight sharp!’

“When I walked into the little house where we were living I must have had a smile on my face that would have cracked a statue. Your grandma took one look at me and clapped her hands and giggled for the joy of it! Then I told her that I had another day’s work for the same gentleman. Well, we had a bit of ground meat and some vegetables we’d gleaned from the surrounding fields. That night was a good one, to be sure.

“The next day, there I was at a quarter to eight exactly where I’d been the day before. At eight the gentleman walked up to me and said, `For today’s work, I vant you should fill in my trench.’ I was thunderstruck! But it was his trench and his money. It was honest work for honest pay. And I was grateful to have both. I spent that second day filling in the trench. I shoveled and tamped and shoveled and tamped. When the day was over it was almost impossible to tell where the trench had been. The gentleman came out and inspected my work again and again pronounced himself satisfied. Then he paid me.

“Little Teddy, your family ate for three weeks (nobody could stretch a food dollar like your grandma) because of the humanity of that saintly man. Do you know what his clothes and hat and long hair were? Neither dad I. I’d never seen a person like that before. Not ever in my life. But look here in this book [he showed me a photo of a Hassidic Jew]. That is exactly what he looked like. What does the caption say the fella in the photo is? A Jew? Well, little Teddy, always remember that your momma and grandma and your uncles Dick, Denny and Jack, all of us ate because of the generosity of a gentleman who was Jewish and who was able to take pity on us and help us while letting us keep our pride. I pray for that man and his family every night and have ever Since then. I want you to pray for them, too.”

And I have.

For decades, I accepted without question the veracity of Grampa’s story. But, with the advance of my own age and critical faculties, I find myself wondering how in the world a Hassidic Jew managed to make his way to the Iowa farmlands of the twenties. For in that area at that time, he would have been very much alone. Then too, I find myself wondering how the N.I.N.A. phenomenon of the mid-19th century could have lasted so long into the 20th century, particularly in an area with as many Irish-Americans as Iowa has.

I suppose Grampa’s story could have been true, but for me, it does not have to have been true. It is still beautiful and teaches so many of the things my grampa wanted to imprint on his playmate and first-born grandchild. And I love him for having come as far as he did within himself and taking the effort to give me a “leg up” so that my life’s pilgrimage could begin by building on his foundation.

But to be safe, I still pray for that man and his family. Grampa would want me to. ♦

Leave a Reply