“For twelve long years I’ve suffered this damned cat…/ though more than once I’ve threatened violence/ the brick and burlap in the river recompense/ for mounds of furballs littering the house.”

– “Grimalkin”

“Grimalkin,” Tom Lynch informs me, “is dead.” I couldn’t help it, I had to know.

The cat lasted almost eight years after the poem was written. “I had told Mike [his son] what would happen if it didn’t die, that I would take it as a sign that I’d have to kill it,” adds Lynch. He doesn’t look as if he’s joking, but neither does he seem to be dancing a jig of happiness at the cat’s final departure.

But then jigs of happiness at news of a death, any death, are not exactly befitting a man of Lynch’s persuasion. He, as well as being an acclaimed writer and poet, is the undertaker in the Michigan town of Milford, a town of “about 15,000 souls.” Undertaker, mortician, funeral director – take your pick. As for himself, he prefers the former term. As a child, explaining to other kids what it was that his father did for a living, Lynch reckoned it all had to do with digging holes and dead bodies.

It’s a long way from Milford, Michigan to Moveen West in County Clare, but Lynch is equally at home in both places. His association with the southwestern Irish county spans three decades, and he still recalls with breathtaking vividness the occasion of his first visit there. The Irish cousins he returned to visit year in, year out are dead now, but Lynch’s love for Clare lives on, and his pride in the little cottage he inherited four years ago is obvious.

A conversation with the writer proves every bit as entertaining and varied as any of his books. With two essay collections and three books of poetry to his name, this is a man who has plenty of fascinating thoughts buzzing around in his head. Modest to a fault, he begs to differ. “I’m not a genius…I’m not going to have that many great thoughts,” he says with a laugh. “Maybe two or three in my lifetime.” While poetry, he says, is about using every word at your disposal and then pruning to find the one that is exactly right for the poem, his essays give him more scope to “inflate” an idea.

Ever the versifier, Lynch resorts to poetic language to describe his writing. “Poetry is the diamond of speech,” he says. “It is the thing that has been pressed, and pushed and tempered as best you can to get rid of anything extra…But all that stuff you’re throwing away – all those images, all those words, all those kind of intellections that might have worked but didn’t – you pick those up, dust them off and turn them into essays.”

And what essays they are. Lynch’s first book, The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade, published in 1996, won an American Book Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award. Critics struggled to outdo each other with superlatives. USA Today hailed his vivid prose an “electricity of writing,” while the New York Times described Lynch as “a cross between Garrison Keillor and…William Butler Yeats.” The comparison is all the more apt considering it was a love of Yeats and other Irish writers that attracted Lynch to Ireland in the first place.

When 21-year-old Tom Lynch arrived at Shannon Airport in February 1970, there were those who thought the young American was mad. His grandfather’s cousins Nora and Tommy Lynch, sister and brother who lived in Moveen West, a tiny hamlet close to the mouth of the majestic Shannon river, couldn’t get over the crazy Yank who’d wanted to visit Ireland at that time of year. Back home in Michigan, Lynch’s mother was just hoping he wouldn’t go native.

Crazy or not, Lynch was made to feel very welcome by his older relatives. After all, they remembered the priest he was named for, they knew all about him, even if his only knowledge of them had been his grandfather’s oft-repeated mantra during grace before meals – “And don’t forget Tommy and Nora Lynch on the banks of the River Shannon.”

A brother of Nora and Tommy’s, Mikey Lynch, lived in Jackson, Michigan, and his picture graced the wall of the little cottage in Moveen West. What Lynch didn’t know at the time was that he was the answer to Nora’s prayers. Literally. She had been waging a battle with the Land Commission, who had approached her about the 40 acres of land she owned but which she and Tommy were growing too old to farm successfully.

Sometime during the summer of 1969, the fiery Nora had dashed off a letter to the “grabbers,” as she contemptuously referred to them, informing the Commission that a young American relation would be arriving 10 months later, and he would take care of the farm. “That was six months before she knew anything about me,” explains Lynch. “So when I wrote she just assumed that God had made good on the lie she had told. And she figured this was an act of God.” The bewildered young visitor only much later realized why this elderly woman insisted on walking the land with him and telling him what areas were good for grazing or reaping hay or whatever.

“I’m just nodding and smiling the whole time, knowing nothing about nothing,” he recalls. “But for her it was really a matter of great pride. The fact that it was their land, and their father’s land and their grandfather’s land before them, I think for Nora to have lost the land on her watch would have been a terrible, terrible thing.”

Lynch spent four months in Ireland on that first visit. He worked for a while in the Great Southern Hotel in Killarney, at the same time that film director David Lean and his Ryan’s Daughter entourage were staying. The night porter’s job had been set up by a Father Kenny, a friend of the Lynch family who had retired to Salthill, Galway. It seems Lynch was kept in the dark a lot that particular summer; he had no clue that the job, and his subsequent firing, were arranged at the behest of his mother. She, fearing that her son would end up staying in Ireland, contacted Fr. Kenny and asked him to get Tom a job that he would then lose without his pride being unduly dented. “I remember being called into the manager’s office and he said, `You’ve done a great job here, but maybe you’ve noticed that most of our guests are Americans,'” recalls Lynch. “I said, `Yes,’ and he said, `So, you’ll probably understand why it’s a real letdown for them to have their bags taken out in the morning by a guy who sounds like he’s from Detroit.’ He said, `Will you understand that I can’t keep you on,’ and I could understand it, I really could. But now that I think about it, I can hear the careful discussion that went on behind the scenes!”

A month later, Lynch was homeward bound, his mother’s crafty plan having worked. The lure of Ireland was to prove irresistible, though, and he visited again just a few months later before settling back into college in the States. When Tommy Lynch died in 1971, young Tom was one of the first people Nora called. “I came back for the funeral and I think that was when she really got the message that I was going to be around for the long haul.”

Not only was he to return to Moveen West time and again, he also brought Nora over to the U.S. on a few occasions, giving her the chance to see the sisters who had emigrated there and never returned home to visit. “I can remember that was upsetting to her,” says Lynch, “seeing the difference between their lives and her life. She didn’t begrudge them, but it alerted her to what her life was.”

With the help of a friend of Lynch’s in Co. Mayo, Nora’s fight against the Land Commission was tacked on to another similar case making its way through the Irish courts system. Reassured that the case would take years to reach its conclusion, Lynch reckoned that as long as Nora outlived whatever happened, everything would be fine. Not only did she outlive the protracted legal battle, Nora lived long enough to rejoice at the disbanding of the Land Commission. When she died in 1992, at the grand old age of 90, she left the cottage and haggard to her cousin the writer, and the acres of farmland to neighbors P.J. and Breda Roche, who had taken care of her as if she were their own blood. Today the couple looks after the little cottage – christened with a simple, stone plaque that reads “Nora’s” – when Lynch is in Michigan.

In his three decades or so as an undertaker, Tom Lynch has seen the best, and worst, of human nature. His prose and poetry reflect both ends of the spectrum. Take “Aubade,” a poem of just four lines that appears in his third collection, Still Life in Milford: “When he was finished hitting her he went/ to work. She woke the boys, sent them to school,/ then hung herself with a belt she’d bought him/ for his birthday. He would never get it.”

Murder, suicide, illnesses that have ravaged people into shells of their former selves, Lynch deals with it all on a regular basis. You wonder how someone copes with all the tragedy. “There are times when it is overwhelming, the sadness that people endure,” he says quietly. “When you see parents burying children, because you are human you understand how that hurts. But it’s not my sadness. The things that make me sad are the things I have invested in, in terms of my attachment.”

His attachments are his four kids – Tom, Heather, Michael and Scan, who range in age from 26 to 20 – and his wife of 10 years, Mary Tata. (Lynch has been divorced from the mother of his kids since 1984.) He all but glows when talking of his family; it’s clear that he is happiest in their presence. “They’re lovely,” he says. “I’m very lucky with my family.” Growing up, he and his siblings were encouraged to join in nightly debates around the dinner table. “We loved to argue, loved to talk,” he recalls. “Words were important to us and we would never say talk was cheap. Talk was what we did.”

Tom Lynch grew up in Michigan, one of nine children. The family’s Irish heritage, he recalls, was never in doubt. “My mother was [Rosemary] O’Hara and my father was [Edward] Lynch and we were told such things as we didn’t have to wear green on St Patrick’s Day because we were Irish,” he grins. “We were well aware of being Irish. It accounted for such things as temper; whenever we’d lose our tempers it was because we were Irish. Drink was another thing…and there was plenty of that.”

There may have been plenty of drink in the background, and no shortage of beer in the house, but Lynch recalls seeing his father drunk on only one occasion. “I remember that what finally stopped him drinking was my mother’s threat that she’d send the boys after him,” recalls Lynch. “And he said, `Don’t ever send my sons into a bar for me.’ That was a peculiarly Irish thing and she would have been aware of that.”

In turn Lynch and some of his siblings would grow up to have their own problems with alcohol (“It is the thirst and sickness that has dogged my people in every generation that I remember,” he writes in Bodies In Motion and At Rest: On Metaphor and Mortality), but he’s been sober now for years. Marriage and kids saw him exist as a “garden-variety suburban boozer,” but the tide quickly tamed after he and his first wife divorced and he got custody of their four children. Eventually he writes with the clarity of hindsight, “I drank because that’s what sack drinkers do, whether to celebrate the good day or compensate for the bad one, whether shit happens or doesn’t happen. Because it is Friday is reason enough. Because it’s November will also do.”

Whether it was genes or circumstance, fate also contrived to land Lynch’s youngest son, Sean, with an addiction to alcohol. In perhaps the most touching essay of his second collection, Lynch writes of his struggle to protect and provide for his son, his overwhelming desire to lift the darkness that has descended on Sean, to give the boy a happy ending. “It hurts so bad to think I cannot save him, protect him, keep him out of harm’s way, shield him from pain,” writes Lynch in an essay entitled “The Way We Are.” “What good are fathers if not for these things? Why can’t he be a boy again, safe from these perils and disasters?”

There is no match for the brightness of Lynch’s smile as he tells me that Sean is, at the time of our conversation, “ten months sober, thank God.” Such is the emotional intimacy of his writing, and the power of his prose, that you find yourself heartily glad to hear the news.

Growing up the son of an undertaker, Lynch experienced first-hand the same protectiveness he has since lavished on his own four kids. Whenever he and his siblings sought permission to do something, their father righteously informed them he had only just buried someone who died doing that exact thing.

We turn into our parents, it is said, and Lynch readily admits that as far as his children are concerned, he’s a worrier. “I’ve been with too many parents who have buried a child and I just don’t want to go there,” he says. “It probably has done [my kids] no good. Because when they say, `What do you think I should do?’ I say, `Outlive me.’ The rest is gravy, you know. I really don’t give a shit as long as they just live longer than me. That’s their duty done as far as I’m concerned. And it’s probably made them less ambitious than they might have been – but as long as they’re alive I don’t care.”

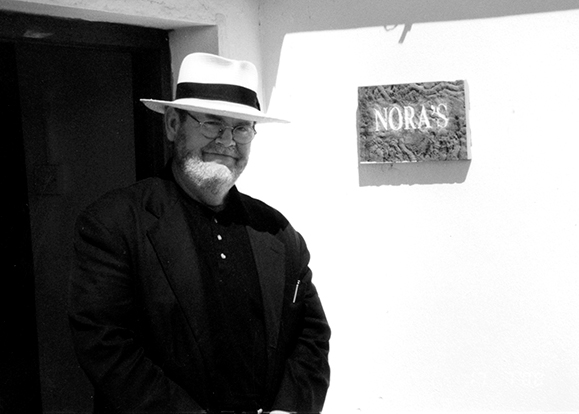

It’s a beautiful sunny day in west Clare and Tom Lynch insists on taking the scenic route from Kilkee, where we initially meet, back to Nora’s cottage. Driving alongside the Clare cliffs, with stunning views as far as the eye can see, he is in an ebullient mood – chatting easily about his current trip and pointing out sights of interest as we travel further into the wilds of west Clare.

Arriving at the cottage, he’s like a proud father anxious to show off his adored child. Flinging open the unlocked door, he bustles inside, stooping slightly as he enters the narrow hallway. A large kitchen and living area have long since replaced the tiny rooms that once comprised the cottage, and Lynch also now has the comfort of indoor plumbing and electricity. It’s a haven of simplicity, a welcoming oasis in this age of streamlined hotel rooms and tourist trappings.

It’s also very much a spiritual retreat for Lynch, and such is his generous nature that he doesn’t like keeping it to himself. Writer friends, and friends of friends, have all availed of the rural hideaway. In a rentals ledger made especially by Des Kenny of Kenny’s Bookshop in Galway, Lynch exhorts his literary tenants to “leave this absentee landlord poems, paragraphs, sentences, phrases well turned out of your own word horde and what you’ve learned.”

And pay up they have. Mayo writer Mike McCormack wrote much of his excellent second novel, Crowe’s Requiem, here and has contributed to the rentals ledger. So too have novelists A.L. Kennedy and Philip Casey and poet Macdara Woods.

So what attracts Lynch to Ireland, what keeps him coming back? “Well,” he pauses, “I think it’s partly the sense that I’ve always had that I’ve seen a way, a lifestyle that was two or maybe three generations behind my own. So I can understand how life was maybe at the turn of the century in America. I actually experienced it here; when I came here first this place had not been inundated with modernity. The life that was being lived here by Tommy and Nora and their neighbors was nearer a life that was 18th century than 20th century.”

It’s also where Nora comes alive for him. “Ireland is still a place where there’s not so much difference between the dead and the living, because even though they’re buffed, the month’s mind is the first observance and every year after there’s a Mass said for them,” notes Lynch. “Nora Lynch has become `the Lord have mercy on her’ – Nora Lynch, she’s still part of the conversation around here.” Lynch’s own parents, who died within a few years of each other – his mother of cancer, his father of a heart attack – still feature regularly in his dreams and he says he talks to them often. “I’ve never had the sense that they’re separate from me,” he muses. “They’re definitely dead, but I’ve never had the sense that I couldn’t draw on whatever wisdom and energy and affection there was.”

It is perhaps this quiet certainty that serves him so well in his chosen career. His clients obviously sense it too; he notes in another essay that he’s often the first person to be called when a Milford resident loses a relative, a fact that annoys and perplexes the town’s priest. “They know they can’t shock me,” is Lynch’s explanation. “I also think the reason people call me is because they’re paying me and they know because they’re paying me that I’ll do whatever I’m supposed to do. I answer the phone. Try a priest at three o’clock in the morning in America and you probably won’t get him. If you call a funeral director you certainly will. That’s the difference.”

Whatever his talents in dealing with those who have just lost a loved one, Tom Lynch is a fine writer, and someone who can always be relied upon for an excellent turn of phrase or a thought-provoking debate. Death, dying and the vagaries of human nature may not strike everyone as the best subjects for leisure reading, but Lynch has a definite gift for raising somewhat morbid topics out of the depths of misery. Consider this, the first line from his book The Undertaking: “Every year I bury a couple hundred of my townspeople.” Doesn’t it just make you want to read more? ♦

Leave a Reply