When Bill Clinton took the stage in Dundalk on his final presidential visit to Ireland last December, he could have had no idea how much of a welcome was waiting.

In the late 1990s, the border town (population 30,000) had almost shaken off its El Paso image, a legacy from the Troubles, and was working hard at promoting itself as a center for multinational investment.

However, after the horrific Omagh bomb in August 1998, it seemed as if the town’s hard work had gone for naught as people once again tarred it as a paramilitary stronghold.

So the Clinton family’s decision to stop off in the town last December generated massive amounts of positive publicity

Chelsea Clinton pronounced it the highlight of her Irish tour, and the thousands of Dundalk people who waited hours for the Clintons to arrive basked in the glow of an unaccustomed public love-in.

But behind the scenes and almost unnoticed by the locals, another U.S. visitor has been quietly changing the face of Dundalk.

Winter Hynes (33) last year walked away from his man-about-town life in Manhattan to take charge of a refugee center here.

Along with his brother Kevin, Hynes ran the successful Chelsea nightspot H2K, but he handed in his notice last year to return to Ireland to run Kincora House, a government-funded refuge for some 40 people (including families) who are seeking asylum in Ireland from some of the worst trouble spots in the world: Nigeria, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Angola, Lithuania, Ghana, Congo, Bulgaria and Georgia.

Hynes, who admits he could be described as having been born with a silver spoon in his mouth, might seem an unlikely candidate for this post. Born in Longford and reared in Dublin – his family used to own the well-known O’Donohoe’s bar in Merrion Row – he spent several years traveling round the globe before finally settling in Manhattan.

But the lure of the Big Apple was not enough to hold this restless young man and he walked away from a lifestyle that the majority of Celtic Cubs would covet.

He also gave up the single life after falling in love with and marrying Bridget, a 26-year-old woman from Nigeria.

It would be easy to dismiss Hynes’ interest in running the refugee center as a consequence of meeting Bridget, but, in fact, it happened the other way round. He met Bridget after he took over the day-to-day running of the place.

I would like to have interviewed Bridget and the other residents for this piece. But the press is barred from interviewing asylum seekers without official permission from the Department of Justice, and the residents were afraid that by talking to me they would endanger their applications for shelter. (This policy has since been changed.)

I learned, however, that Bridget’s family was massacred in Nigeria and that she made her way to Ireland knowing little about the place. When she discovered a statue to Saint Bridget outside Dundalk, explaining the origins of her name, she felt that fate had brought her there.

Bridget is one of the lucky ones. Her marriage to Hynes means that she can apply for legal residency, and will eventually be allowed to work. Others are not so fortunate.

Sitting in his paper-strewn basement office, Hynes talks about the problems facing the residents, and the accusations that they are lazy “spongers” with mobile phones who live high on the Irish taxpayer’s support.

“How can anyone be accused of sponging when all they are getting is fifteen pounds a week?” asks Hynes. “Most of the money goes to pay for their mobile phones, which is the only way they can keep in contact with their families.

“One of our residents was smuggled here at huge expense by his family. He cries every time he speaks to them as they think he’s earning money and not sending it to them. The Irish public think he’s sponging, and all the poor guy is trying to do is hang on until the department makes a decision on his application.”

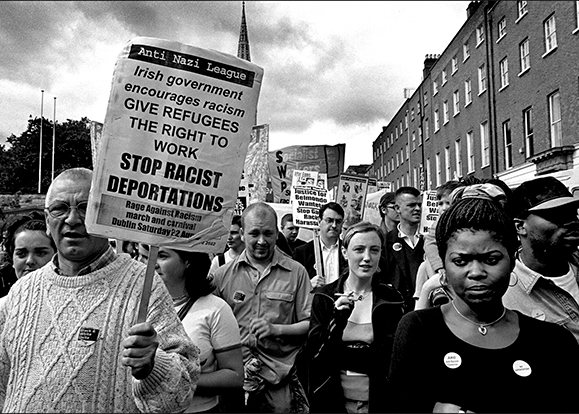

Though Ireland is suffering from a labor shortage, refugees who arrive in Ireland after April 1999 are barred from seeking work while applications are processed.

“Boredom is the biggest problem for all our residents. They don’t like to be left sitting around. The majority of them have undergone hugely traumatic experiences and if they could work, it would at least take some of the pressure off them,” says Hynes. He is furious at the government’s handling of the situation, and points out that Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Bertie Ahem is presiding over a non-existent immigration policy, although Ahem himself demanded an amnesty for 70,000 undocumented Irish living in the U.S. in the 1980s.

Another accusation lobbed at the refugees is that they are “disease carrying.” Doctors have voiced concerns about refugees who are not coming forward for health screening, particularly those who arrived before 1999 and are living in private housing.

Hynes answers that many refugees are afraid of anything that is linked to the government, much in the same way that the Irish in America historically avoided reporting crime to the police for fear of being revealed as undocumented and thus deported. He believes that it is incumbent on the government to provide full health facilities to asylum seekers on a confidential basis and to reassure them that their status, whether legal or illegal, will not be jeopardized.

New laws, which include mandatory fingerprinting for all asylum seekers over the age of 14, have added to their fears, as has the fact that Justice Minister John O’Donoghue is apparently going to liaise with Romanian and Nigerian police (known to be among the most corrupt forces in the world).

“We have gone everywhere,” says Hynes of the Irish diaspora, “and eventually we were accepted everywhere, and now that we are in a position to return the favor, we are turning our backs on people who need our help.”

In a recent Guardian article, a young refugee recounted his early years in Rwanda being taught by an Irish Catholic priest.

“He told us lots of stories about Ireland, how lovely it was, how lucky we would be if we had just one day here. Well, now I know. When I walk down the streets I keep on looking around, just to check that no one is going to hit me.”

There are disquieting reports that some primary school teachers are opposing the admission of asylum seekers’ children to schools because of unproven health fears.

“If our nation’s teachers are passing this message on to the public, it will be very difficult to teach children about integration and social inclusion,” Hynes points out.

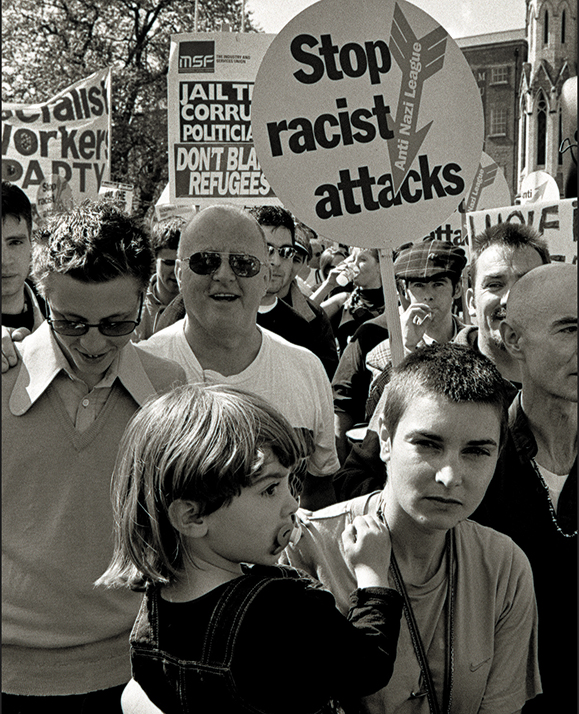

Meanwhile, “refugee” has become the favorite playground taunt, and reports of racist incidents are on the rise, particularly in Dublin, where refugees have been beaten, stabbed and spat at on the street.

Since a child born in Ireland is automatically entitled to citizenship and the mother to residency, “women especially are being vilified in the media for having their children here,” says Hynes.

Irish newspapers recently reported “a crisis in Dublin maternity hospitals,” telling how Dublin’s three main maternity units are “bursting at the seams” because of the “upsurge” in births to asylum seekers.

However, the figures do not bear this out. Roughly 1,200 children were born to asylum seekers last year, while Ireland’s birth rate is hovering around the 50,000 mark, down from 1980’s figure of 74,388.

It is hard to see how a drop of 24,000 births has become a crisis with the addition of 1,200 births. And Hynes is angry at the lack of public debate on the matter and the fact that so many reports go unchallenged.

Despite the assumption that Ireland is being “flooded by refugees,” the country doesn’t even figure in the United Nations Human Rights Commission’s table of increases in refugee population.

And the latest 10-year trends from the UN (1990 to 1999) show Ireland’s refusal rate of asylum applications at 86.1 percent, compared with 72.7 percent in Holland (which has argued for less restrictive work permits to be adopted through the EU), 58.6 percent in Norway, 75.2 percent in Belgium, 27.6 percent in Denmark, 52.7 per cent in Finland, and 80 percent in France.

Germany, which has seen 1,879,590 people apply for asylum over the same time frame, and Italy are the only EU countries with higher refusal rates than Ireland, at 92.4 and 86.6 percent respectively.

If Ireland’s refugees were allowed to work, they could help fill up the estimated 200,000 job vacancies that are expected to arise by 2003.

In his excellent book The Uninvited Jeremy Harding notes that “Some of the most impoverished people to arrive in Britain after the Second World War were the Ugandan Asians – refugees in all but name – most of whose wealth had been expropriated by Idi Amin. By the end of the century they had established themselves as a bastion of British retail – with vantage points in finance, pharmaceuticals, engineering and property.”

The OECD estimates that by 2020, nearly 80 million people will be needed to keep the U.S., Australia and Britain living in the manner to which they have become accustomed.

There is no reason to suppose that Ireland will not need some of these 80 million migrants seeing as we are now part of the developed world. The very people who chafed at the refugee births in Dublin’s maternity hospitals last year may one day welcome them.

In the meantime, if your name is Timothy or Pat, there is indeed a welcome on the mat, but if your name is Adib or Belmondo, the prevailing mindset in Ireland is that you can go right back to where ever it is that you came from. ♦

Leave a Reply