For the last 40 years, Americans have been fixated on the trials, tribulations and tragedies of the Kennedy family. Yet as the nation has kept its eyes focused on the Bobbys, Teddys and John-Johns of America’s “Royal Family,” a new Kennedy leader has quietly emerged. And this time, it’s a woman.

℘℘℘

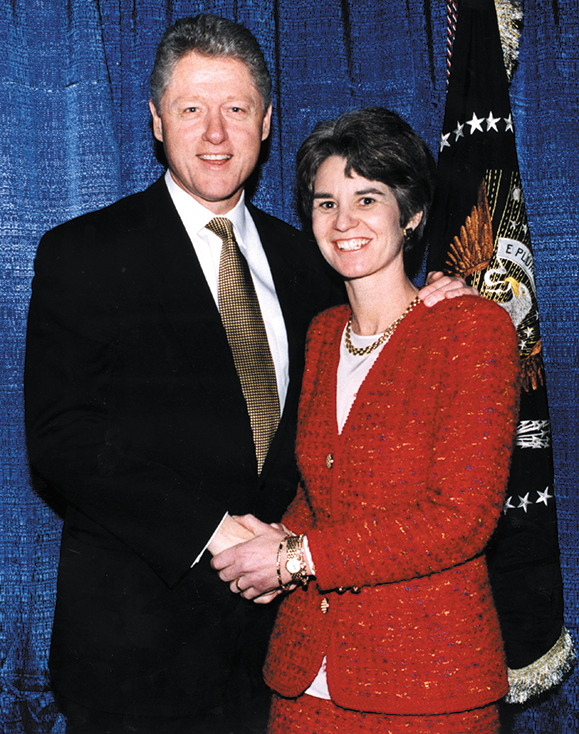

Maryland Lieutenant Governor Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, the eldest child of the late Senator Robert F. Kennedy, has surfaced as the new political leader of the family’s next generation. The 49-year-old mother of four is poised to accomplish what no other Kennedy has achieved in the century and a half since Patrick Kennedy left his 80 acres in County Wexford, Ireland, to seek his American fortune. Townsend is the heavy favorite to become the first Kennedy governor.

Although the Maryland race is two years away. early voter polls show her with a double-digit percentage lead over her closest Republican rival in a state with a 2-1 Democratic voter edge. With one of the most powerful names in national politics, a moxie for the game and the trademark toothy grin, Townsend has established herself as a force that many Maryland political veterans view as unbeatable. “It’s her race to lose,” said Herb Smith, Maryland’s veteran political science professor from Western Maryland College. “She has the money, name recognition, a national network and good staff.” Yet even Townsend will agree it wasn’t supposed to be this way. Unlike the exalted boys, Kennedy women weren’t encouraged to run for public office.

Americans most remember the Kennedy females – led by Townsend’s grandmother, Rose, and her mother, Ethel – as the emotional family bedrock when the news of death and destruction washed ashore at the famous Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. “I don’t think that it’s just particularly true with my family,” Townsend said. “It was the culture of the time that dictated that the men would run and not the girls.” Yet anyone close to Townsend will tell you: this is no typical Kennedy woman. She possesses the same spunk, passion, determination and political instinct that has helped Kennedy men build one of the world’s great political dynasties that began in 1880 in a run-down Boston saloon owned by her great-great-grandfather.

As the Kennedys move into their third century at the forefront of American politics, Townsend adds her own inspiring story. The tale is that of an All-American girl from an All-American family who is fueled by a duty to public service instilled by a legendary father she considered her best friend, assassinated during his 1968 presidential bid, shortly before her 17th birthday. She was born on the 4th of July, 1951, the first granddaughter of 20th-century Kennedy family patriarch Joseph Kennedy. A self-described “tomboy,” Townsend remembers a happy childhood filled with Kennedy traditions such as playing touch football on the lawn, sailing off Cape Cod, and her personal favorite, riding rugged, graceful horses in national competitions. Kennedy parents used the activities to teach their children to become fierce competitors, never settling for second best.

Religion also played an influential role, Townsend said. Nights in the RFK home were reserved for daily prayers, the rosary and Bible readings, planting the Christian ethic to do the right thing. She was 10 when her uncle became the nation’s first Irish Catholic president and her dad served as U.S. Attorney General. When her cousins occupied the White House beginning in 1960, the Kennedy children viewed it more as a fun house. They attended their own private movie screenings, and one of Townsend’s fondest memories is of the President returning in his helicopter, piling all the shrieking kids in a golf cart and racing across the White House lawn.

Yet as the eldest child of 10, Kathleen felt a responsibility to set an example, a pressure that almost caused her to join the convent. With her father and Uncle John working in Washington, D.C., the family lived in nearby McLean, Virginia. Their critical posts at the top of the U.S. government guaranteed that politics and national affairs dominated the Kennedy household. Four newspapers sat on the breakfast table daily and the blare of television news constantly filled the house. “In a sense, we had a serious childhood,” Townsend said. “At dinner, we were quizzed on news events.”

Her selection as the leader of the next Kennedy generation happened at the tender age of 12. Two days after her father helped bury his brother, killed in Dallas by Lee Harvey Oswald on November 22, 1963, RFK scrawled a note to his little girl: “As the oldest of the Kennedy grandchildren you have a particular responsibility now,” her father wrote. “Be kind to others and work for your country. Love, Daddy.”

She almost didn’t make it. She was an instant away from being yet another victim of the so-called “Kennedy curse.” At 14, her horse, Attorney General, crushed her during a riding competition, leaving Kathleen in a coma. Hearing the news while sailing off Cape Cod, her father risked his life diving into choppy seas to climb aboard a Coast Guard cutter, ensuring that he would be the first person she saw when she opened her eyes three days later.

She attended a Northwest Washington parochial school until her junior year in high school when she transferred to a Vermont boarding school. There on June, 4, 1968, she learned the news that her father had been shot in Los Angeles after winning the California Democratic presidential primary. Weeks shy of her 17th birthday, Kathleen stood by her father’s bedside as he took his last breaths.

“People say when someone dies, the pain will eventually go away,” Townsend once told Oprah Winfrey. “It doesn’t.” Over three decades later, her father’s death remains off-limits as a discussion topic. But on a recent rainy day in Baltimore, Townsend reflected on what she considered the most important lesson he taught. She remembers that when riding through cities, her father would always drive through the poorest neighborhoods to remind his children how the less fortunate lived. “I remember one time in Washington, D.C. when he took me to dedicate a new playground,” she said. “He said, `Kathleen, these children are your age, look around. There are no trees in this neighborhood, there are no parks, there is no place to swing on a swing.'”

Townsend is reminded of her father every day. No matter where she goes, people converge to tell her about how his life touched them. “I feel blessed because a day doesn’t go by where someone doesn’t say that they got involved in politics or in teaching because of my parents,” Townsend said. “When I went to South Africa in 1985, people would quote verbatim the speech my father made there in 1967.”

She attended Radcliffe College, where she is remembered for her intellect and passion for history and literature. She married a graduate student, her literature tutor, David Townsend. They moved to Santa Fe, N.M., where her husband gained a teaching job while Kathleen wrote for a local newspaper. She later worked as a state Human Rights Commission investigator and studied law at the University of New Mexico. As he obtained his law degree from Yale, Kathleen opened a private practice. She gained her first front row seat to Kennedy politics working for her Uncle Ted’s unsuccessful 1980 presidential bid. She managed his 1982 Senate campaign, then served as a policy aide to then Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis.

The Townsends moved to Baltimore County in the mid-1980s to be near her husband’s parents. By 1992, Townsend found herself working in the Maryland Department of Education, where she first put her fingerprints on state policy. At her urging, Maryland became the first state in the nation to require high school students to perform community service. A year later, she joined the agency her father once directed, the U.S. Justice Department, overseeing grants to police departments and community groups. That led to her Police Corps idea. Under the program, police officers get their college expenses paid in return for working for four years after graduation in American cities. In 1994, Townsend’s opportunity to jump into politics surfaced when Maryland Governor Parris N. Glendening, a little-known county executive from the Washington, D.C. suburbs, ran for the open governor’s seat. Townsend fit the former political science professor’s running-mate criteria. She provided necessary political balance from the middle of the state, loved policy and brought political muscle to the campaign. Glendening won by 6,000 votes.

Since becoming lieutenant governor, Townsend has played an active role in governing the state. Not wanting to relegate her to a ceremonial vice role, Glendening placed her in charge of weighty issues such as the criminal justice system, the state police and economic development.

She gained quick attention for her HotSpots program, which pools state and federal money to high crime areas. Her tough stances, including support for the death penalty and welfare-to-work programs, gain her the label of a centrist Democrat, a political role her father helped pioneer.

Like her father, who became one of the first Democrats to question the New Deal and welfare programs, Townsend has split from the liberal wing of the party, establishing herself as a New Democrat. Although most of her famous political family, including one of her own sisters, have vehemently opposed the death penalty, Townsend supports capital punishment, in part due to her own experiences. That her father’s assassin, Sirhan Sirhan, is still living is “horrible,” Townsend has said.

“I think it’s a very, very tough decision,” Townsend recently told the National Press Club. “But I think some people commit heinous crimes, and I think it’s appropriate in those cases.”

And on another national issue that Townsend speaks to from the heart, Maryland became the first state in the nation to require trigger locks on all new guns sold, a program called Smart Guns.

Yet in a state long dominated by white-male politicians, skeptical critics still view Townsend as a political lightweight. Without the Kennedy name, they say, she would be relegated to minor service as a government policy wonk.

They point to Townsend’s unsuccessful 1986 campaign to unseat suburban Republican Congresswoman Helen Bentley. Bentley trounced her by 18 percentage points, making her the first Kennedy in history to lose a general election. And despite her commanding lead in the early polls for the governor’s race, opponents have begun stockpiling their political ammunition, picking apart her eight-year record as lieutenant governor.

The state’s boot camp program for juvenile criminals, under Townsend’s criminal justice supervision, is in shambles after camp guards were found beating teen prisoners. One youth with a heart problem recently died during strenuous exercises despite his complaints of physical ills. Townsend is also struggling to repair the ailing court system in Baltimore, which suffers a backlog of cases in a city with over 300 murders a year and an estimated 60,000 drug addicts.

Townsend appointed the state’s respected former public safety director to restructure the juvenile justice department and has become directly involved in participating in Baltimore’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council to help repair the court. “I do my best,” Townsend said in response to her critics. “The best test is what you do with what you’ve got.”

Townsend’s most touted crime initiative, her “Break the Cycle” probation program, recently came under fire after a participant on parole became the chief suspect in the November shooting death of a Maryland State Trooper. The 23-year-old suspect violated probation 72 times without penalty. Townsend called the lapse a mistake by one parole officer, defending her program for cutting the number of repeat offenders by 25 percent and those addicted to drugs in half.

Maryland marches into a new century with a hearty $1 billion budget surplus. And a recent census study showed that Maryland is the national economic leader, with the highest median family income level and lowest poverty rate in the nation for the last two years.

Townsend has already caught the proud eye of national Democratic leaders who view her as a future party leader. Last summer she addressed the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, and polls showed her as a possible female contender to serve as Vice President Al Gore’s running mate. Other voter polls recently taken list Townsend as a woman in American politics with the best chance of becoming the nation’s first female president.

“Kathleen Kennedy Townsend is a unique person because she has brought her core beliefs to politics in a way that few have and she’s been able to put those into action,” Al From, president of the national Democratic Leadership Council, said at a recent meeting in Baltimore. “We got together in 1988 around our common belief in John Kennedy’s civic ethic that Americans have an obligation not just to take from the country, but to give something back. A lot of us talk about it, Kathleen did something about it.”

Eight years in the governor’s office could be the perfect springboard for Townsend to eventually jump into national politics just 42 miles down the road in Washington. Yet Townsend tempers the hype, saying that although she intends to be in politics a long time, she focuses on one day at a time.

She learned the lesson through the tremendous tragedies that her family has suffered, including the death of two brothers and the loss a year ago of her cousin, John Jr. Making a lasting impact wherever she may be at the moment is the goal, she said, whether it’s wrestling Baltimore’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council to make the city safer or sitting down each night to talk with her daughters about their day.

“Death makes you conscious of how mortal you are,” Townsend said. “You don’t know where you’re going to be in two days. When you’ve seen tough times, you know you can’t wait.”

That personal principle is fueled by the living spirit of her father, an advocate for the poor who lived a privileged life yet was murdered while reaching to shake the outstretched hand of a $75 a week Mexican dishwasher. “My father would say `It’s only God and angels who are lookers-on,'” Townsend said. “Each of us must get involved.” ♦

Leave a Reply