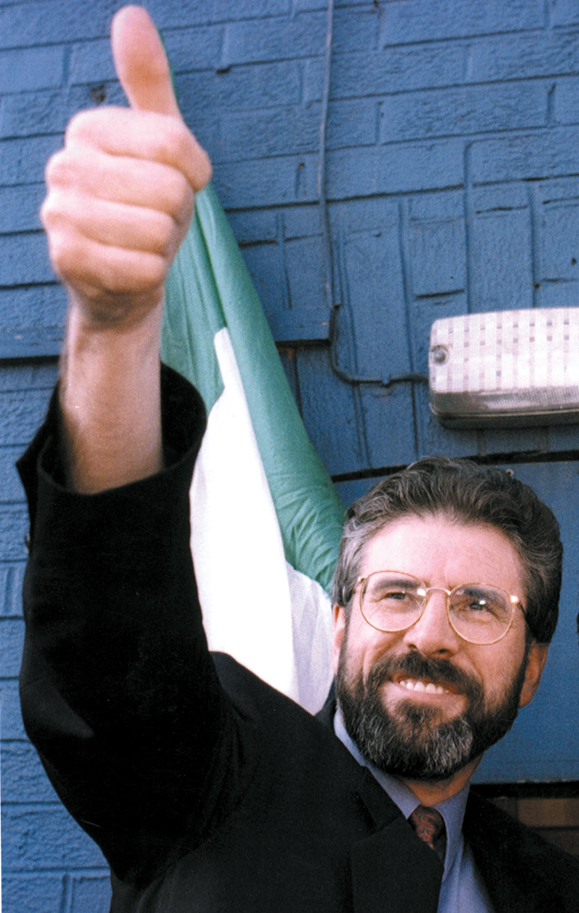

Kelly Candaele talks to Gerry Adams about recent developments in Northern Ireland.

℘℘℘

Gerry Adams is no stranger to violence. In 1984, he told reporters that he believed there was a ninety percent chance he would be assassinated. Two months later, he was shot by loyalist paramilitaries. While he denies ever having been a member of the IRA, most close observers of the twenty-five years of war in Northern Ireland believe it is unlikely he could have risen to his current position as president of Sinn Féin, the party that provides a political voice to the Irish Republican Army, without emerging from the crucible of that organization.

Adams grew up in staunchly working-class West Belfast, an area that formed his political development and has sustained his involvement in republican activism to this day. Raised in what he calls a “spinal” republican family that stretches back generations, it is not surprising that when the civil rights campaign exploded in the late 1960s, Adams left his job as a bartender and threw himself into full-time republican activism.

By the early 70s Adams had become a major figure within the republican movement. Jailed in 1972 when internment without trial was introduced, he was one of the key participants in secret negotiations with the British that ultimately failed. He was also in jail from 1973 until 1977.

Adams eventually rose to the presidency of Sinn Féin in 1983 after a split within the IRA over strategy and long-held republican principles. In his first address as Sinn Féin president, Adams told the party congress that armed struggle was “a morally correct form of resistance” against the British government’s presence in Northern Ireland. By the late 1980s, Adams and other prominent republicans began to rethink that strategy when it became apparent that there would be no military solution to Northern Ireland’s “Troubles.”

Working with John Hume, the more moderate leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), who had consistently argued for a more peaceful approach, they developed a set of principles that became the foundation for the eventual Good Friday peace agreement signed in 1998 and approved overwhelmingly by voters in both Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic.

While most Unionists regard Adams as a duplicitous “godfather” of IRA violence, republicans regard him as a staunch community defender and the primary figure who can deliver peace in Northern Ireland. He has twice been elected as a Member of Parliament for West Belfast, and he is a member of the new Northern Ireland Assembly

Adams was interviewed in New York City while there to attend a Sinn Féin fundraising event. His visit came in the midst of another crisis in the peace process precipitated by the refusal of Northern Ireland’s First Minister David Trimble to allow Sinn Féin representation on the cross-border political bodies set up as part of the Good Friday Agreement. And the British government’s refusal to make the policing changes drawn up in the Patten Report.

Adams, age 52, married Colette McArdle in 1971. They have one son.

IA: This peace process has moved from crisis to crisis. David Trimble, the First Minister of the Assembly, has refused to nominate Sinn Féin representatives to the cross-border institutions set up under the Good Friday Agreement due to his belief that the IRA has not kept its commitments on moving towards decommissioning of weapons. Do you see a resolution to the current impasse?

Adams: I have significant concerns about the British government’s handling of this situation. It was fairly easy to see this crisis coming. I said to them in June, “Make sure you deliver on demilitarization, make sure you deliver on policing,” because if you leave it until the autumn, David Trimble is going to call a conference, or his detractors are going to call a conference and you’re going to find it difficult. I told Prime Minister Tony Blair we can’t have this continuous renegotiation of our human rights. We can’t have a continuous negotiation of the equality agenda.

IA: Aren’t the British trying to save David Trimble, a pro peace agreement leader of a very divided party, and by saving him save the peace process, in the same way they have to understand the difficulties you have in bringing the IRA along?

Adams: I think the peace process is a bigger thing than the political process. What the British government has done is to make their commitments in terms of both the political and the peace process conditional and secondary to their management of Unionism. And that’s the fatal flaw. That immediately gives people on the Unionist side the ability to dictate the pace and quality of the developments that are required. For example, if the objective becomes to save David Trimble, then that’s giving the advantage to David Trimble, and he wouldn’t be a good political leader if he didn’t use that to seek concessions that suited his particular argument. The peace process cannot be reduced to the fortunes of one political leader.

IA: Isn’t that use of leverage occurring on both sides? Aren’t IRA weapons the biggest piece of leverage you maintain in order to achieve movement on police reform, demilitarization and other major issues?

Adams: In terms of the political process these are all stand-alone issues. We deserve a decent policing service, we deserve political institutions that people can have ownership of. The British government established a commission. The Patten Commission came up with recommendations. Now, Sinn Féin would have gone for much more radical recommendations, but we said fair enough, Patten is a compromise and maybe this is the beginning of a new policing service. What did the British government do? They emasculated it.

IA: Peter Mandelson, the British Secretary for Northern Ireland, has stated that the core of the Patten Commission recommendations are being proposed for implementation by the British government.

Adams: The British proposals retain as much power in either the hands of a Chief Constable or in a British Secretary of State. This is a move away from a democratic accountability and the concept of civic policing which is required. The arguments the Unionists took up around Patten were about the symbols of the new police force. The big gutting out of Patten is on a British agenda, not only a Unionist agenda. It is the British state saying we are not prepared to do away with what has essentially been a weapon in the state arsenal.

The whole issue of policing is a touchstone issue. If you want to know how far the movement has to go you only have to look at the number of Patten recommendations. What you had was a totally unaccountable quasi-paramilitary police service that acted as an arm of the state which had behind it a judicial system that was subordinate to it. That isn’t propaganda, it’s a matter of factual record. The first thing you want is a young person from a republican background or neighborhood to be able to say, “I’m going to join this new policing service” and to have peer approval to do it. So they have to have equality within that policing service. The way it stands right now, no one from the broadly democratic nationalist republican section is going to support what the British government is proposing.

IA: The IRA made a statement in May that they would reengage with the Independent Commission on Disarmament to begin to work through the details of decommissioning weapons. That hasn’t been done. Why?

Adams: First of all, David Trimble’s move doesn’t just involve the disenfranchisement of Sinn Féin ministers. He has also called for a moratorium on implementing the Patten recommendations. He has also called for a change in the remit of the international independent commission on decommissioning. And he has also said there will be a review by his party in January of all of this. The IRA’s position is very straightforward. First it said it would allow some of its arms dumps to be inspected, which was a huge move. It said it was prepared to put weapons verifiably beyond use.

IA: Is the inspection of arms dumps synonymous with putting weapons permanently and verifiably beyond use?

Adams: It could, but I don’t think that was the intention. This is an evolving process. I think the intention is underscored in the IRA statement which described this as a confidence-building measure mostly aimed towards the Unionists. First of all, for the first time in 200 years of resistance to British rule you have the primary republican organization saying “Yes, we are prepared to verifiably put weapons beyond use.” They then outlined the context for doing this. They said they were prepared to discuss this with the commission provided the British kept to their side of the bargain. And the British side of the bargain was contained in the British government/Irish government statement. The British government have not kept to their side of the bargain. They have re-militarized, they have not dealt with the policing issue, and they have not made the type of progress they promised.

In a totally paradoxical way, a British Prime Minister has to reinforce an IRA leadership so that it can be more flexible as it moves ahead. And an IRA leadership has to reinforce the position of a British Prime Minister. From the IRA’s point of view, it has done that. It did the first inspection in June despite the British not moving and another inspection two weeks ago. The two inspectors said the IRA kept their commitments.

IA: If the IRA war is really over, why not decommission weapons and thereby take the moral high ground and remove that as an issue? Is it simply that they can’t politically do that?

Adams: There are a number of reasons. First of all, within the IRA the process is leadership led, and leaderships can only do so much as they have to manage their own constituency. The most important thing within the IRA constituency is to avoid any serious splits because you would end up with the worst of all possible scenarios. You only have to look at what happened in the Middle East to see how a peace process can fall apart, with all of the tragedy that comes with it. Secondly, the IRA weapons are silent and the weapons that are being used at the moment, the visible ones, are the ones being used by the British. It comes down to making politics work. Do you convince people who have weapons to give them up before they are satisfied that progress can be made by other means? What we have succeeded in doing is getting people to silence their weapons and go to the sidelines while the rest of us take over the playing field. I’m convinced that the weapons issue is going to be resolved. Here we have an IRA on cessation and we have political institutions in place against all the odds. It’s generally considered to be a success story.

History is sometimes made by a watershed event that changes everything, or by a process of change. We’re involved in a process of change. It’s slow and it’s frustrating but it’s better than war.

IA: You’ve made an analogy to the Middle East where there has been a return to daily violence. Are you saying that the same kind of dynamic might take place in Northern Ireland?

Adams: I don’t want to do that. You can look at the Middle East and see the failure or the refusal to lead to some progress that leads to a huge frustration and lack of ownership by the different elements involved; then they see no way to protest or to draw attention to what’s happening except through the scenes we have seen and all of the deaths. So the challenge for us is to prevent that from happening in Ireland.

I do think, incidentally, that the White House has a very clear view of this. A month ago I spoke to a very senior official who said to me that the British need to know that the biggest enemy of this peace process is complacency. The peace process isn’t irreversible and it needs to be consolidated.

IA: The Real IRA is continuing in a violent attempt to remove the British from Northern Ireland. Do you feel they are a threat to your leadership and therefore a threat to the peace process?

Adams: They make a lot of threatening remarks about our leadership but I take that as going along with the territory. We have to recognize they are a very small group and they don’t have any popular support and they don’t have a strategy. Most republicans, including the bulk of republicans who were involved in armed actions, support the strategy we have developed and which we are pursuing.

IA: A small group can do a great deal of damage when they have explosives. In order for this peace process to survive, does the Real IRA need to be put down?

Adams: I don’t think that works. I think that what is needed is to build upon the rejection by the vast majority of people in Ireland of this group, not to give them room to gain any tolerance within republican neighborhoods or within broad republican heartlands. So we have to remove any justification, however spurious, and make politics work as a way of moving forward.

IA: Some of your republican critics who were active in the IRA, who spent time in jail and went on hunger strike, say this is a partitionist settlement that legitimizes continued British rule in Northern Ireland after twenty-five years of sacrifice. How do you answer these arguments?

Adams: I can argue tactically and strategically and I can intellectualize or theorize all of these matters. What I have to say, with some sadness, is that these criticisms don’t represent any significant tendency within republican activism. That’s the hard reality. Some of the people associated with this group did good service for the republican cause and I would never take that away from them. But they have not been active in a very long time. Some of the spokespersons have not been active since the late 1970s.

IA: In your autobiography you make the argument that in the beginning of the modern “Troubles” in the late 1960s, IRA actions were basically defensive. But throughout the 70s and 80s the IRA was very proactive in their armed campaign. In Catholic “just war” theology violence has to be a last resort, primarily defensive in nature, must have popular support, and the end achieved must outweigh the suffering imposed to achieve it. How do you morally and intellectually justify the IRA campaign?

Adams: In terms of moral theory it depends on which Catholic theologians you talk to. The Catholic bishops reinforced and justified British Army killings on Bloody Sunday in Derry. Catholic bishops in the U.S. justified the war in Vietnam. If you ask me to look back over the last thirty years, there are things that happened that are unjustifiable. I think that’s the nature of war, and I think anyone who will try and give you a textbook idea of a clean war is engaging mainly in a public relations exercise. There are other things that happened as the result of the human condition, the political condition that existed at that time. People get involved in armed action because they don’t see an alternative or because there is no alternative. I’ve never been carded away by this silliness of glamorizing war. The outworking of all of this process I hope will bring about an end of violence forever, permanently and completely doing away with any possibility of war ever re-erupting in Ireland.

IA: You have a commitment to a unified Ireland. You have an agreement in place which in some sense changes the traditional republican view of self-determination in that there is now an acceptance of the issue of consent of the Unionists to change the constitutional relationship with Britain. How do you now see that ultimate goal of Irish unity taking place?

Adams: The primary political objective of Irish republicanism is our national independence and unity, and that has not changed. There may be different strategies and political tactics deployed alongside the task of trying to build a cohesive sustainable peace process, but that is a good thing because it’s better than war. While the British are still there and they maintain jurisdiction, the reality is that it’s now quite like a relationship in a marriage with children where the partners decide they are going to break up but they wait until the children have grown up. That’s the only logical explanation for where the British are constitutionally. They say they are now prepared to leave and they are not there forever. Tony Blair has to look back over hundreds of years of conflict and look forward fifteen or twenty years up the road to a totally new era between the two islands and come up with unprecedented initiatives.

IA: Could you see a situation where parity and equality between the communities reaches a state where the issue of joining with the Republic of Ireland becomes less and less important?

Adams: There may be people within the Unionist family who have a genuine love for Britain. But at the core, many Unionists are Unionists because it makes them top dog and they are used to it. Now if you bring about equality then there aren’t any top dogs and people have to look for some other form of identification. I think Nelson Mandela had it right when he said that his task was to set about liberating his oppressors.

IA: The definition of “national identity” is changing in a globalized world. You have the beginnings in Northern Ireland of a “bi-national state” that is built into the structure of the political institutions. In the words of the peace agreement, a citizen can identify himself and be accepted as “Irish, British or both…” Has this dynamic changed your thinking on the nature of Irish nationalism?

Adams: Nationalism is of great importance because we don’t have national independence. It isn’t so important in the United States, and probably your nationalism is really patriotism. The core of the political issue internally in Ireland is one of political allegiance. It’s one section of the people who think their political allegiance lies with the union and with Britain, and the rest of us who believe our political allegiance lies with that concept of nationhood with the Irish people.

IA: President Clinton overrode British policy by granting you a visa to visit the United States in 1984. Do you have some concern that a President Bush or Gore might go back to deferring to the British in relation to Northern Ireland?

Adams: I don’t have those concerns because the conviction that I have is based upon the success of what has occurred. You think back before this change of approach by President Clinton. What we had was year after year, decade after decade of conflict, a whole apparatus of inequality, a lack of rights, a lack of entitlements, huge militarization of the situation, and thousands of prisoners. Now we have a strategy and process in place to change that. And not least because of a change in United States foreign policy on these matters. People within both the Democratic and Republican parties have worked on these issues. So I’m convinced that we will see a continuation. ♦

Leave a Reply