Titanic Town, the fictional story of a Northern Ireland woman who mounts crusade for peace in 1972, is not the first movie to attempt to trade on James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster Titanic. The European film The Chambermaid on the Titanic barely managed to beat Cameron to the screen but had its title changed to The Chambermaid in 1998 U.S. advertising. That probably discouraged other filmmakers from inflating the importance of their stories simply by setting them on the ill-fated ocean liner.

But there is some justification for the title Titanic Town. The legendary ship was built in Belfast, and as Cameron’s film shows, many of the third-class passengers abandoned to their fate by the British owners were Irish. Belfast has commanded worldwide attention as the focus of the British-Irish political struggle for more than three decades now. This truly is a titanic upheaval, but the film’s title also carries a layer of irony, suggesting that the hopes for peace, like the building of the “unsinkable” liner, may be a quixotic enterprise.

However, the pervasive feeling of unreality presented by Titanic Town is less a philosophical stance than a result of dubious aesthetic choices. Anne Devlin’s screenplay is based on the autobiographical novel by Mary Costello, who fictionalized the story of her relationship with her mother, Tess Costello. The mother on screen, played by Julie Walters, is called Bernie McPhelimy; newcomer Nuala O’Neill portrays her seventeen-year-old daughter, Anne, a medical student dating a young IRA man (Ciaran McMenamin).

Wary of shooting in the mean streets of Belfast itself, the filmmakers used a housing estate in North London to represent the McPhelimys’ neighborhood, an IRA stronghold. This decision, although understandable from a practical standpoint, gives the film a feeling of artificiality, removing it from the poverty and chaos of the original setting. The script also compresses the events of several years into a single year.

Buried in the fine print of the end credits we read, “This film is not a documentary but a drama based on true events which took place in Belfast in the 1970s. Some of the events and characters have been fictionalized for dramatic purposes.” The film’s publicity material wants to have it both ways, declaring that Titanic Town is “a true story.” As Vladimir Nabokov remarked, to call something a true story is “an insult both to truth and to art.”

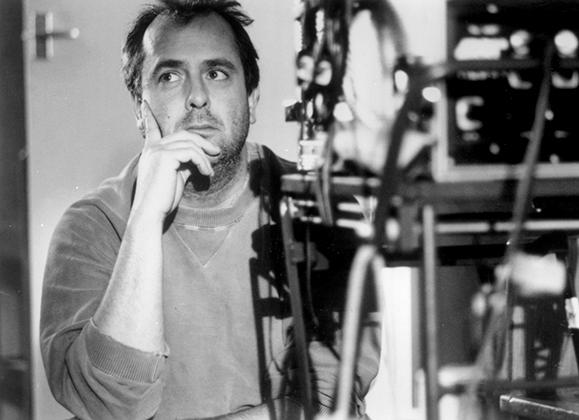

Originally released in 1999, Titanic Town opened last fall in the U.S. and will be available on American home video this year. Director Roger Michell’s film seems destined for that medium, because it has the thematically simplistic, visually restricted ambience of a TV movie, and it was produced by two prolific makers of TV dramas for the BBC, George Faber and Charles Pattinson. Among the backers of Titanic Town are BBC Films and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland’s National Lottery Fund.

The marvelous Julie Walters, who is half Irish and half English, creates a believably stubborn and doughty character in Bernie McPhelimy. But she is not well served by her fellow filmmakers. They are bizarrely promoting Titanic Town as “a timely, uplifting comedy [sic], set in the era of bellbottoms and Van Morrison, back when The Troubles all began.” Faber captured the political ambivalence of the project by explaining, “The situation in Northern Ireland is pretty intractable, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to change things, and this film is a celebration of trying.”

Perhaps unintentionally, what Titanic Town most clearly demonstrates is the danger of political naiveté. Bernie has the well-meaning recklessness of an energetic bricklayer on the road to hell. She is provoked to political action when she sees an innocent woman shot on her street, killed in crossfire between IRA and British soldiers. What most incenses Bernie is that her many IRA-supporting neighbors won’t face the truth that the woman was killed by an IRA bullet.

Bernie’s protest evolves from merely wanting to “stop the shooting during the day” in her neighborhood to the grander ambition of “trying to take the gun out of politics.” But here again she misses the mark, for as Mao Zedong famously put it, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Anyone trying to challenge the brutality of realpolitik faces a rough battle indeed. Bernie lacks the intellectual acumen and political sophistication to understand the complexity of her own situation.

Titanic Town raises the great and complex issue of pacifism but fails to fully explore its implications. Bernie’s simplistic aversion to violence hardly is a reasoned or principled stance to compare with the organized passive resistance practiced in India by Gandhi (who took inspiration from Irish resistance to British colonial rule) or in the United States by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The self-absorbed Bernie wouldn’t know what Gandhi meant when he said, “There go my people: I must hurry up and follow them, for I am their leader.”

Even Bernie’s family tums against her after the children are hounded at school and they are all made pariahs in the neighborhood. Anne accurately observes that her mother’s stance “looks anti-IRA instead of propeace.” The frightening scenes of British soldiers invading the neighborhood are echoed by an equally ugly scene of neighbors invading Bernie’s house and ultimately driving them out.

“Why is everybody making me responsible for everything that happens?” Bernie wonders.

Since period films are just as much about the time of their release as about the time when they take place, Titanic Town clearly asks to be read as a prefiguration of the current peace talks. But rather than calling for the British to leave Ireland, the intended message seems one of compassionate resignation toward human suffering. As Bernie puts it, “I’d like to see us have the humanity to condemn the shootin’ of a soldier. I’d like to see the army show real regret over the shootin’ of civilians.”

Regret won’t buy you a cup of coffee, and portraying Bernie as a heroic crusader seriously misrepresents the actual effect of her crusade. She takes a position that plays directly into the Machiavellian hands of the British ruling authorities, who find her a delightful puppet. Circulating a petition in the neighborhood against IRA violence, she presents it to Stormont Castle, not stopping to think that it can be used to identify the IRA sympathizers who refused to sign it.

The petition eventually grows to contain the signatures of more than 25,000 Belfast residents. But nothing of substance changes as a result. Gradually realizing that she has become a de facto collaborator with the British, Bernie insists that she’s a “peacemaker…not an informer.” To her daughter, she says defensively, “I wasn’t wrong, Anne. Because I was naive doesn’t mean I was wrong.”

The shallowness of the film’s political discourse fails to place these tragic ironies into a thoughtful context. The tunnel vision of Titanic Town, its narrow concentration on personal issues at the expense of the broader historical picture, keeps it from dealing with the underlying causes of the political problems caused by British rule, or with the poverty and discrimination suffered by Catholics in the North.

For a far superior movie about ordinary women involved in the real issues of Northern Ireland, go rent the underrated 1996 film Some Mother’s Son, starring Helen Mirren and Fionnula Flanagan as mothers on opposite sides of the political fence who are united by their sons’ IRA activities. The rich exploration of human and political complexities by writer-director Terry George and writer-producer Jim Sheridan in Some Mother’s Son shows up Titanic Town for what it is, a comic-book version of recent history. ♦

Leave a Reply