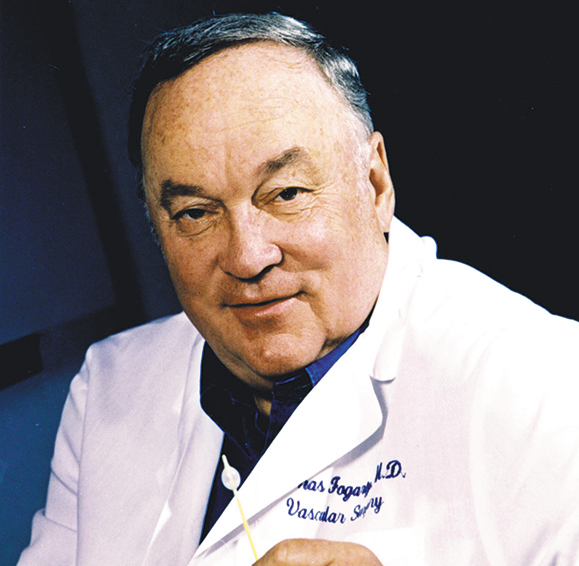

“Tom Fogarty epitomized American ingenuity and has made a lasting and beneficial impact on society.” As a child he built model airplanes. As an adult he has saved lives with his medical inventions.

℘℘℘

In this age of skepticism, it’s reassuring to know that at least two cherished American myths – Horatio Alger s model of the self-made man and the image of the visionary inventor tinkering in his garage – still exist in the person of Dr. Thomas J. Fogarty. This renowned Irish-American heart surgeon, who started his inventing career as a boy in Cincinnati, is responsible for devices that have revolutionized cardiovascular surgery over the past four decades. His products are credited with making such surgery less threatening to the lives of tens of millions of people.

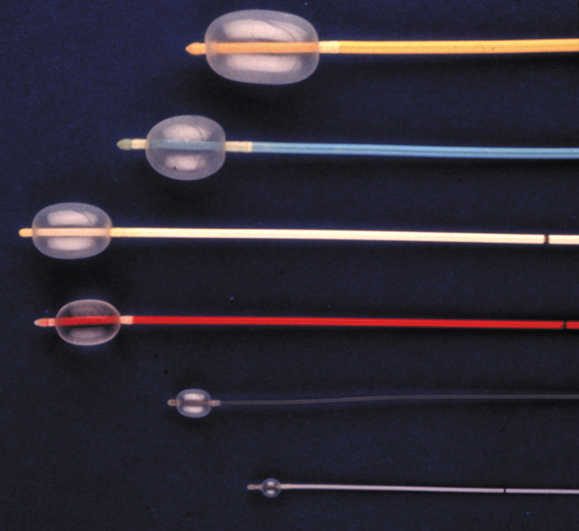

Fogarty’s first medical invention, the Fogarty… Arterial Embolectomy Catheter, was patented in 1963. The device has made it possible for surgeons to remove blood clots from arteries without the kind of drastic, invasive cutting previously employed. The old methods caused half the patients to die during surgery and half the survivors to require limb amputations. Now the operation has a 95 percent survival rate, and only five percent of the survivors need amputations.

Dr. Fogarty has been awarded about seventy other patents, including some for refinements of his basic embolectomy catheter. He was part of the surgical teams that performed the first heart transplant in the United States and the first successful artificial heart valve implant. Fogarty told Irish America, “In a global sense I’m interested in technology that makes patient care more efficient and less intrusive and damaging to the patient. It could be a service that you create or a device or a combination of those two.”

Describing him as “the consummate inventor, always tinkering and trying new ways of approaching problems,” Dr. William R. Brody, president of Johns Hopkins University, says that Fogarty “has singlehandedly changed the face of cardiovascular surgery.”

The 66-year-old Fogarty splits his time between the Stanford University Medical Center in Palo Alto, California, where he is a professor of surgery, and his Fogarty Engineering, Inc., in nearby Portola Valley. From an inconspicuous office complex in a shopping mall, Fogarty and his staff of experts continually develop new medical products. Most of the products are spun off into smaller start-up companies, eventually being sold or licensed to outside firms for distribution.

Last year, Fogarty received two prestigious awards for his pioneering achievements. He was given the Lemelson-MIT prize for invention and innovation, carrying a $500,000 prize that he is using to start a foundation “that will reward individuals who apply innovation to patient care.” Fogarty also was honored by the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation Foundation with its Laufman-Greatbatch prize for his “unique and significant contribution to the advancement of medical instrumentation.”

“Tom Fogarty epitomizes American ingenuity and has made a lasting and beneficial impact on society,” said Lester C. Thurow, board chairman of the Lemelson-MIT program. “He is not only remarkably inventive but is also a dedicated mentor and inspiring role model for young scientists, engineers, and clinicians.”

Proud of his Irish roots, Fogarty traces his ancestry back to Tipperary. His grandfather William Henry Fogarty was the first of his family to emigrate to America, around 1890. According to the doctor, “The Fogartys were Fenians – people dedicated to getting rid of foreign influence in Ireland, no matter what it was – and so they were either killed or exported. I got an old county almanac with a picture in it showing three Fogartys hanging in a town square. They were all brothers. There were a Tom, a John, and a William hanging, and all the names were in our family.”

Dr. Fogarty’s grandfather settled in Jackson, Ohio, where he became an innkeeper. The doctor’s father, William Henry Jr., who moved to Cincinnati, designed railroad engines. “My father died when I was eight years old,” Dr. Fogarty recalls, “so if I wanted anything or if my mother wanted anything, it was up to me to take care of it.” The mechanical aptitude he displayed soon led to his first try at inventing.

“I built model airplanes, and very early I made a model of a flying wing,” he recalls. “It didn’t fly very well. I just thought, `Why can’t we have all wing and have the pilots in the wing?’ Toward the end of World War II, both the United States and the Nazis were messing around with flying wings, but they never had a functional one.”

Besides building and selling model planes for the kids in his neighborhood, young Tom competed in the soapbox derby, making his own wooden cars. He became known as “The Flying Irishman” for racing in his green automobile. His first successful invention was a clutch for a motor scooter.

A friend whose nickname was Pinhead had a Cushman scooter with a mechanical shift. Fogarty bought one too, but found that “if you were in high gear going up a hill and you shifted to low gear, the scooter would be about ten yards ahead and your ass would be on the pavement because it would lurch ahead. So we started messing around trying to figure out how you could change that to a very smooth transition. From that came up the concept of a clutch mechanism. We built one in a motor scooter repair shop. Pinhead had a part-time job and I’d go down and help him. We ended up using a lot of their bits and parts of machinery to design the system.”

Fogarty didn’t realize that working in the shop gave the shop ownership rights to the device, which soon became standard equipment on Cushman scooters and is still in use. From that experience he learned a valuable lesson: “If you’re going to do something, don’t do it in somebody else’s shop.”

Fogarty received invaluable on-the-job training for his future career when he went to work at Cincinnati’s Good Samaritan Hospital while only in eighth grade. “They called me `The Oxygen Boy.’ I rolled the oxygen tanks around and I would take the oxygen tents to the bedsides. And I cleaned the stomach pumps.”

Although the job had a starting salary of only eighteen cents an hour, it further honed his mechanical skills. He fixed the stomach pumps and learned to run the steam autoclave, a pressurized, steam-heated vessel used for sterilizing operating instruments. “When somebody wasn’t available to run the one in the operating room, I would go do that. Then I started cleaning the instruments. I got to know some of the nurses, and they said, `You can be a scrub technician,’ which means you hand the surgeon instruments.”

There he witnessed the horrors of invasive cardiovascular operations: “It was an operation that never worked. They’d open up the whole area so you’d have an incision from the chest to the legs, and then you’d have incisions all the way up and down your legs. And they’d try to pick this [clot] material out. It was a very mutilating attempt. So it was pretty easy to say, `This ain’t working.'”

By his senior year of high school, Fogarty wanted to become a doctor. He won his M.D. from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. Working in his attic while a surgical resident at the University of Oregon Medical School, he came up with the prototype for his inflatable embolectomy catheter in 1960. The device had the inspired simplicity that is characteristic of many great inventions. Using fly-fishing techniques he learned in boyhood, Fogarty attached the fingertip of a small latex surgical glove to a catheter with fine thread and cement.

Asked how he thought of this innovative way of removing blood clots, he explains, “I just said, `Christ Almighty, they’re making these incisions all over the place. If they had a pathway, they could put something up there. Once you get into that pathway, all you’ve got to do is have a way to pull it out.’ Almost intuitively I said, `Well, it’s a balloon on a stick.’ It actually pulls out the clot by mechanical traction.”

Fogarty’s guiding principle ever since has been to make health care both safer and “more accessible. I hate the word `cheaper.’ A better word is `cost-effective.’ The way you make it more accessible is by addressing the issue of cost. But you have to make people understand that not being effective involves a huge cost. I look at what are big needs in the area of medicine.”

Recently Fogarty has been working on a relatively inexpensive sleep monitoring device, now awaiting FDA approval. “If it’s not properly taken care of, sleep apnea [temporary suspension of breathing while sleeping] is probably responsible for most vehicular accidents, because people fall asleep at the wheel. And those people are not very effective during the day. They fall asleep at their desks at work, they lose efficiency, they can’t really function because they’re so tired all the time. It’s a huge public health problem, but it’s correctable.”

Many years back, while operating on heart patients, Fogarty would find evidence of hypertension that had not been diagnosed. That led him to “the concept that hypertension may occur during sleep and not during the ambulatory hours. That’s connected with the syndrome of sleep apnea or sleep disorders. What happens is if you don’t breathe, you retain CO2, and as you retain CO2, you elevate your blood pressure. So I thought, OK, we’ve got to make sure we diagnose this. There’s no good way of diagnosing sleep disorders short of sending somebody into the hospital or a sleep lab, hooking them up to a bunch of stuff, and monitoring them during their sleep. You’re immediately in an artificial environment, and this costs a lot of money.

“So the concept is, `Can we come up with something that you do in your native environment, at home while you’re asleep?’ That involves sensor technology we developed here at Fogarty Engineering. It’s a bedside unit about the size of a big clock radio. They place the sensors and plug it into a module. It encodes all the data. They just ship it back by Federal Express and we get it and download it and analyze the data. Then we mail the doctor the results of that particular study.

“There are a lot of people who are never diagnosed because they can’t afford it; this will be a lot less expensive. The wife would say to her husband, `You’re a pain in the ass. I’ll spend $500 to figure this out.’ She may not spend $2500, but she’ll spend $500.”

Fogarty also has developed an innovative device to treat breast cancer, the Mammotome Breast Biopsy System. Acquired by Johnson &Johnson, it is “a mechanism by which we can take out tumors that are bigger than a marble in a less invasive way. When you go to take out a lesion that’s either physically palpable or bigger than a marble, about 20 percent of the time you’re never certain you got it all out. So you end up doing a second procedure or doing a simple mastectomy. We’ve designed a technology so that once you have something that is identifiable either by a mammogram or physically, you can always make sure you got the whole thing out.”

Remarkably relaxed and jovial despite having so many demands on his time, Fogarty enjoys juggling multiple interests. Asked how he manages to run several companies simultaneously, he succinctly replies, “Good people.” But he adds with an impish smile, “I just holler and scream.”

Fogarty even has a profitable sideline as a winemaker. Thomas Fogarty Winery & Vineyards in Portola Valley, on 60 acres in the Santa Cruz Mountains, was opened in 1981 and now produces 15,000 cases of premium varietal wine annually. Fogarty makes the business decisions for the winery but does not run the day-to-day operations. He and his wife, Rosalee, live on the grounds – one of the vineyards is their front yard.

When I asked Dr. Fogarty how much of his time is devoted to brainstorming for new ideas, he replied, “Most of it. See, for me it’s not discontinuous. It’s part of the process of what I do. When I see or treat a patient, I always think, `OK, has this been done the best way it could have been done?’ And if you think about that, sometimes the answer is no, and then you start addressing that. It’s just a continuum of the same process of trying to make things better.” ♦

My dad is from Tipperary and I am a Fogarty. Am Irish and Live in London Uk.

I think you are amazing. Another realtive of mine was Senator John Fogarty of Rhode Island.

Keep going Tom and enjoy your wine. Slainte

Mary

My dad is from Tipperary and I am a Fogarty born in Ireland.

Keep going Tom and enjoy your wine. Slainte

Mary