Sweet fiddle music muffles street sounds, thick carpet softens your footsteps, and lace curtains filter the daylight. Fireside chairs before a fireplace invite you to linger over the photos from the past.

At Photo Antiquities, a museum of 19th century photography, the years fall away slowly until Frank Watters, the curator, strides in carrying a musket and wearing a replica of General Michael Corcoran’s Civil War uniform.

Watters, 36, extends his hand and breaks into a smile. “You’ll have to excuse me, I’m off to a school.” This soldier with an Irish brogue knows how to hold the attention of his young students, as he tells the story of Corcoran, his hero.

Watters, a Dublin photographer, moved to Pittsburgh with his wife in 1989. He found work at the Pittsburgh Camera Exchange, occasionally traveling with his boss Bruce Klein, who was gathering a collection of old photographs.

One trip he made to Gettysburg changed Watters’ life. “It made the hair stand up on my arms, and it still does,” he said of his visit to the memorial which commemorates the Irish Brigade. Out of New York and Massachusetts, the brigade, under the leadership of General Corcoran, stood out for the courage they showed in some of the fiercest battles of the Civil War. Phillip Thomas Tucker, author of Celtic Warriors in Blue, writes, “The very sight of the flapping battle flags of the Irish Brigade was enough to cause the Confederates to lament, `Here comes that damned green flag again!'”

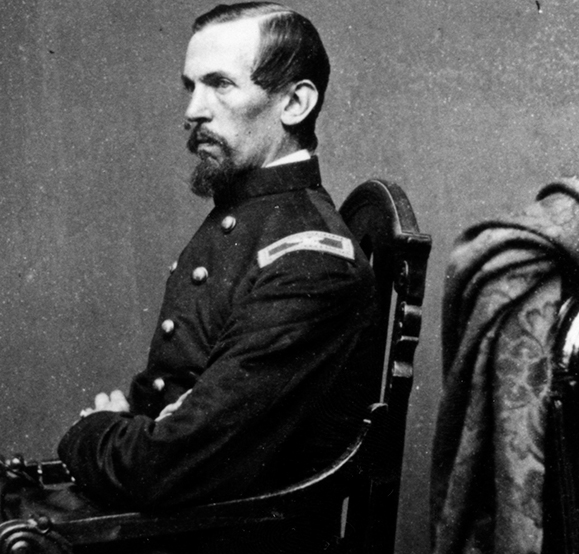

Watters was especially taken with the story of Corcoran, who was born in Sligo in 1827. A member of the Ribbonmen, a secret society who committed acts in defiance of British rule, Corcoran immigrated to New York in 1849, and soon joined the Fighting 69th, the Irish-American regiment, rising to the rank of Colonel.

When Corcoran’s regiment was asked to parade before the Prince of Wales and his men refused, Corcoran accepted their decision. Angry citizens demanded that he be court martialed, but the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861 intervened and the 69th Militia was called into action.

On July 21, Corcoran was wounded at the Battle of Bull Run, and taken prisoner. He spent the next 13 months in Confederate prisons, until he was finally released in exchange for a Southern officer.

Corcoran was promoted to general and treated as a war hero. He was invited to the White House to have dinner with Lincoln. Urged to run for Congress, he volunteered instead to provide a legion of Irish Americans to continue the fight to preserve the Union. Within three weeks of his release from prison, 2,500 men had joined his Irish Legion.

The Legion went to Virginia, but Corcoran, plagued with fever and weakness from his imprisonment, fell from his horse and died on December 22, 1863. He was 36.

As an Irish expatriate, Watters found in Corcoran the link to his Irish heritage. “I felt a need to have something of Ireland to pass on to my son and my daughter.”

Watters has also passed something of Ireland and Irish American history to hundreds of other children as well, by visiting schools to tell the story of General Corcoran and the Irish Brigade. He has also lectured at Civil War re-enactments, historical societies and universities.

Describing his visits to kindergarten classes, Watters points out, “I always stop and get a couple rolls of shiny new copper pennies. I get their attention when I enter in uniform with my sword. The teacher announces that I am Brigadier General Michael Corcoran. I ask them `Who knows what I am?’ They answer `A Civil War soldier.’ Then I ask, `Who knows who was president during the Civil War?’ I take out my pennies, and give everyone a coin. I say `Whoever tells me who is the president on the back, gets the pennies I have left.’ I talk a bit about President Lincoln and what the Civil War was about. Inevitably they ask if they can try on the uniform. So we take photos with the cap or boots on everyone.” Watters carefully modifies his presentation to the varying age groups. “With the upper grades, we pick out twelve who act as raw recruits, and take them through the day of a soldier.”

“With high school students,” he continues, “it’s all fact-based. I ask the teacher to have them read up on a specific battle, one in which the Irish Brigade played a part, such as Bull Run, Gettysburg, the defenses of Washington, Fredericksburg, and Antietam. We discuss different strategies, and different personalities. I like them to know of the Irish participation of 150,000 soldiers in the war. I always tell them why the Irish Brigade wore sprigs of green at Fredericksburg, their bullet ridden flag had been sent away for repair, and that’s how they kept together.”

Frank said, “When I go somewhere, like Gettysburg, in uniform, I always meet some children who remember me from a lecture.”

Watters is currently writing a book about Corcoran, entitled “In an Honest Cause,” a line from a poem by the Irish poet Thomas Davis. “This is his passion. He’s driven to write this book,” says his wife, Shelley.

Watters said he has no choice in the matter. “I didn’t pick him [Corcoran]. He picked me,” he says with a chuckle. ♦

I would love to know if you have any information about his relatives or antecedents . my grandmother was Mary Ann Corcoran and there is a query that we are related through her to Michael Corcoran. Coincidentally most of my siblings and I were born in ballymote county Sligo. Any information you have would be of great interest to me many thanks and thank you for the article above.

tess.reynolds79@gmail.com