Two successful Irish Americans share an experience of giving…more than money.

℘℘℘

Mary Pat Lyons O’Connor listened to the old woman, her grandfather’s sister, Margaret, as she spun her narratives of the Irish Famine and the small fenced hillocks, famine graves, where hundreds of the nameless lie buried. The two women were in the sitting room of a three-room farm cottage in Feakle, County Clare, and most of one wall was taken up by a huge hearth in which a turf fire burned steadily. Above the hearth were various knickknacks, and Mary Pat found herself stating at one of them: it was a doubled-over swatch of soiled, tatty off-white cloth, about an inch wide and a foot long, hanging at a careless angle from a single nail.

“And what is that, Aunt Margaret?” Mary Pat asked, pointing to the length of braided cloth.

“A tie,” the old woman said. “A necktie. My mother left it for me. She used to make them for the lads, the ones walking the roads to get to the boats, so they could make a better appearance when looking for jobs in America.”

It was after the Famine, Aunt Margaret explained, a century and more before her young visitor from America had introduced herself as a relative and sat back to chat in the sitting room of her father’s ancestral home, “My mother told me she always hoped that if one of her sons needed help in America, someone would be there to give it.”

In that moment Mary Pat Lyons O’Connor of Chicago, just 22 years old in 1970 and visiting Ireland for the first time, came face to face with her history and the devastation of the Irish Famine. “There’s a reason,” she says today, “why on a per capita basis Irish Americans donate more to famine relief than any other ethnic group. History has taught us: It’s not a level playing field; there is such a thing as injustice; there’s plenty of food, but people are starving and dying. And it doesn’t have to happen.”

Mary Pat, who runs her own executive search firm Lyons O’Connor &Co., and supports a number of charities, decided that giving a check is not always enough. She went one step further and volunteered with Concern Worldwide, the Irish relief and development organization that presently has some 3,000 volunteers working in 23 countries.

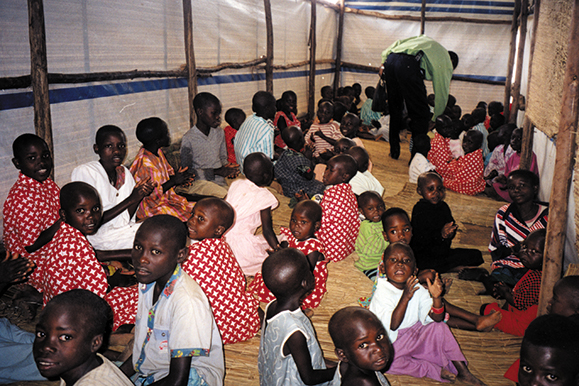

“I wanted to see the whole truth of what the Concern people had to deal with in the field,” she says. The “truth” was far harsher than she’d imagined back in Chicago, where her primary focus had been as a fundraiser. Her first trip, in 1998, was to a Haiti slum called St. Martin, where hundreds of corrugated tin shacks lean haphazardly against each other even as they sink inexorably into a slimy “foundation” of refuse and mud. A canal running through the center serves as a latrine, a garbage dump and a playground. Diphtheria, malaria, dysentery and malnutrition are common among the slum dwellers. And in nearby Petionville Prison children are detained “indefinitely” for stealing food.

But there is also a medical clinic, which Lyons O’Connor’s own dedicated fund-raising efforts helped to build. It is clean. It has bathrooms and fresh water, two nurses who work daily and a doctor on rotation from the Haitian Ministry of Health who stops by on a scheduled basis.

“All we did was make a few phone calls and have a few meetings that featured Dan Casey’s famous shepherd’s pie, and we got the money for that clinic,” she marvels. “Now 60,000 women and children have access to a medical center, where there wasn’t one before. It’s real, concrete and mortar. Basic health needs such as nutrition and vaccinations are being addressed. Women and children queue each day as far as the eye can see. Once you sit on the sand with these little ones holding your hand you know you can make a difference.”

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

Marty Keating visited Kosovo and Albania with Concern in the summer of 1999. The war with Serbia had just ended, and 800,000 Kosovars had returned home to total destruction — houses, schools and whole villages were leveled.

“The first task was to help the returnees locate and bury their dead…many had been dumped in village wells, along with oxen and other livestock. So the water was fouled and new wells had to be dug, in addition to the burials,” he recalls.

“In each village the refugees mounted a rough oversized poster covered with photographs of the men still missing. When their bodies were found or, in rare cases, when the men came out of the mountains alive, the photos were marked and then removed.”

While refugees lived in temporary plastic tent cities, Concern’s volunteers, some of them retired Irish and British army veterans who are experts in construction and logistics, led teams of paid local workers in the swift rehabilitation of 700 homes.

“Actually,” Keating explains, “each `home’ would be one room in a burned-out house. A room with new windows and tile block walls, a solid concrete floor, a door that could lock and a potbellied stove for heat and cooking. Just to get each family through the coming winter.”

Despite the carnage, the spirit of the people, Keating saw, was strangely vibrant. “They gave us the food off their tables, whatever it was.” he says, “We were going from house to house, hearing their awful stories: of fathers, brothers, sons and cousins butchered. The houses are gone, there’s no school, and still they’re filled with hope for the future.

“These two old men were living in tent city waiting for volunteers to finish their one-room `homes.’ One of the men told me that he’d lived in the village for 85 years, and that when he’d come back after the war there was nothing left…not his house, not a tractor, not a cow, nothing. There were no records left — no drivers or marriage licenses, no banking or mortgage records, no way to register a car or prove ownership of anything, no way to get a passport to travel. But this old man and his friend hugged us and kissed us, and thanked us for ending the killing though of course we hadn’t. He said to us, `I am so happy to be back. We will rebuild, and go on'”

In another village Concern’s Kosovo country director Dominic McSorley estimated it would take about $10,000 to rebuild two burned-out schools. Each one-story dirt-floored structure was bullet-riddled, and in need of ground-up rehabilitation — walls, windows, ceilings, doors, bathrooms. “l said `OK, you’ll have ten grand, and two schools,’ and it was done,” Keating explains.

Keating always wanted to help. “I grew up in a household with eight kids and parents who believed in sharing and hand-me-downs and kindness to strangers,” he explains. He studied for the priesthood but when it wasn’t the right fit he diverted to the study of philosophy and, ultimately, to a degree in business. As he moved up the Wall Street ladder as a professional bond trader he was also involved in a growing number of charities. He has a longstanding affiliation with the Kennedy Child Study Center, and was instrumental along with Woolworth CEO Bill Lavin in getting the “Toys for Guns” program off the ground; by its conclusion, the innovative program helped get 25,000 guns off New York’s streets. “There was an eight-year-old who wanted a pair of Air Jordans,” Keating remembers, “so he came in with an Uzi submachine gun. He said he got it from his 11-year-old brother.”

Keating has also founded several college scholarship programs, one in the name of Sister Maura Clark, one of the seven teaching nuns murdered in El Salvador during that nation’s civil war. She’d lived in Keating’s Brooklyn neighborhood when they were kids. “In 1945 my brother was struck by a bus and killed,” Keating says. “Maura came over to the house that night with a pint of ice cream. She said she knew that when my mom was sad she always had ice cream.” Keating never forgot it.

He became involved with Concern when he met Dominic McSorley, who’d served as country director in Cambodia and Rwanda before moving to Concern’s offices in New York and then Dublin.

“Here was a guy,” Keating says, “who’d been a lawyer, and who basically had given his life for 17 or 18 years, in the most challenging, difficult and often dangerous circumstances.

“I think he knew that if he could get me in the field I’d get the fever. He was right. Because I know now not only that I can make a difference, but how I can make a difference.”

The challenge for Irish organizations such as Concern is to tap into the spirit of giving that exists in Irish Americans, whose souls have been shaped by their own history.

One problem, Lyons O’Connor says, is that in many Irish American families “you just didn’t talk about the famine. I’d ask a lot of questions at an early age, and my dad, my Aunt Anne and anybody I asked would change the subject. As though there was something shameful about it. The pain was still too new, too raw, too real…”

It was only when she traveled to Ireland (where she ended up marrying, raising two children, and obtaining two university degrees and a career) that her questions were answered.

“In Ireland, relatives were willing to tell me the stories of the civil war and of the famine. Our part of the county was hit very, very hard, there were terrible and cruel evictions of tenant farmers in Scariff and Feakle near Killaloe, the destitution was extended and made worse by coercion and manipulation at the political level. I learned then that it wasn’t just an act of nature that led to such misery, it was the actions that people took against other people.”

Before and after: The school in Rushiq that Marty Keating raised funds to restore.

Back in Chicago, years later and now aware of her history, she began taking actions for people, and not against them, as an Irish American woman who had done well and now sought to do something in return.

Her first major commitment was to Chicago’s Haymarket House, a center for recovering alcoholics and drug addicts. “There was this six-foot-six black woman, Sheila, and I was terrified of her. She was pregnant, and for some reason when she was in the hospital to give birth, she asked for me and I went.” The two became friends and have stayed that way, each the other’s teacher and student. Mary Pat has watched as Sheila reclaimed her life, attending college even as she’s raised five children. “She’s my hero,” Lyons O’Connor says, though she still wonders why Sheila reached out to her. “Maybe it was because I just kept showing up. Yes,” she says, pausing to think about it. “It was the showing up.”

Show up is what Lyons O’Connor does, most recently in Cambodia, where she filled in for a Concern aid worker who wanted to go home to Ireland for the holidays. She worked in a reforestation program in Reang Sey Province and saw other long-term projects bearing fruit. “In our own famine in Ireland, we’d depended on a single crop and when it failed we were ruined. It is the same thing in Cambodia, with rice. So Concern are teaching the farmers not to be solely dependent on one crop, but to build credit and savings through a micro-finance program, so that they can buy and raise a pig which they can breed.”

In Reang Sey the volunteer from Chicago who’d seen her friend Sheila prevail against terrible odds now saw other women doing the same.

Where before there’d been nothing but a dusty patch of land, with people in the commune missing legs and arms from landmines before it had been cleared, now there was a nursery where women raised seedlings to give new life to the forest depleted by illegal logging and soil erosion. The women earn money for their work and a young woman, Chhoun Sokhuk, showed Lyons O’Connor the dwindling rice stores beneath her house, explaining that her earnings, while meager, had freed her from the fear of going without food.

“She told me, `Now I can take care of my parents, and my sister and her four children,'” Lyons O’Connor remembers. “And she wasn’t alone. Concern volunteers had constructed a water well at a women’s training center where other women learned skills that could earn money — weaving, hair-dressing, sewing — and other life skills that could protect their families’ health and well-being.”

And what did Lyons O’Connor learn in Cambodia and Haiti? “It’s that a mother, a mother anywhere, has an absolute determination to feed her children. She will walk for five days, starve herself, borrow money to buy a bucket to wash windows to buy food. Anything, whatever it takes, to mind her children, to care for them.”

All anyone would have to do, Lyons O’Connor says, is to look such a woman or child in the eye. She says, “Then you get an idea of the difference you can make.

“The more than one million Irish who escaped the Famine back home by coming through America’s front door were offered a life-saving second chance,” Lyons O’Connor adds. And Irish Americans can offer that same second chance to people in need. “It’s not that every CEO or successful Irish American ought to go to one of Concern’s mission countries, but if they did go they would see what I’ve seen. That there’s work to be done, work that matters. “This is all about passing it on. It’s just like that tie my Aunt Margaret showed me in that sitting room in Feakle. All those years ago.” ♦

Leave a Reply