Commencing with convicts, feared and despised, and followed by free immigrants and settlers, the Irish became the dynamic force in Australia’s evolution into a nation.

℘℘℘

The eyes of the world were on Australia this past September, as Sydney hosted the 2000 Olympic Games. A close observer will have noted that many of the Australian athletes, including swimmer Susie O’Neill and cyclist Shane Kelly, are of Irish descent. In terms of Irish-derived proportion of its population, Australia is the most “Irish” country in the world, outside Ireland, with up to a third of its 19 million population having some Irish ancestry.

In no other British settlement were the Irish so central to the composition and evolution of a new nation than they were in the making of Australia. Unlike America, where the Irish were one of a number of nationalities that contributed to the melting pot, in Australia they were the sole significant element of ethnic diversity, the only major non-English culture, save for the Scots.

Since the arrival in 1788 of the small number of jailers and prisoners who began the penal colony, it was the Irish minority alone who questioned and challenged the exclusive dominance of the majority’s English-oriented culture and religion. The Irish, until recent times, have been the dynamic force at the center of the evolution of Australia’s national character. They helped steer Australia away from being a respectable little Britain of the south, towards a more egalitarian and plural society. In fact, they have become so much part of what is seen as the dominant Australian establishment and culture that the newer migrant groups refer to Australia’s mainline culture not as English, but as Anglo-Celtic.

The Irish-born Archbishop Mannix of Melbourne, 1916. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Susie O’Neill celebrated winning the gold medal in the women’s 200m freestyle at the Sydney Olympics, 2000.

This position was not won easily: “We are Englishmen,” thundered the Melbourne Age in 1883, “and this is an English colony…we do not intend to let a handful of `foreigners’…impugn our loyalties to the hard-won traditions of race.” The “foreigners” were the Irish who refused to abandon their identity.

The dominant assumption was that Australia should be a replica of England. The Irish challenge to that became, in a creative and productive social and political relationship, a continuing debate, always vigorous, sometimes bitter, even violent, about what kind of country Australia should be. In recent times, the Irish-Australians, including author Thomas Keneally and labor leader and former prime minister Paul Keating, have been at the forefront of a movement seeking to remove Australia from the British commonwealth.

In fact, all the major incidents of protest in the assertion and development of Australian democracy have been Irish-led and supported. The first convict rebellion in March 1804, at Castle Hill, now a Sydney suburb, was led by two Irishmen, Philip Cunningham and William Johnston, adopting the cry, “Death or Liberty!” from the 1798 Rebellion in Ireland which had led to their transportation.

The Irish “Tipperary Boys” were the vital influence in the Eureka Stockade gold diggers’ rebellion in Ballarat, Victoria in 1854. In that insurrection, which became the central point of Australia’s democratic legacy, 863 diggers, half of whom were Irish, and led by Irishmen, took up arms against government harassment and license fees.

In 1916-17, the Irish-horn Archbishop Mannix of Melbourne led the campaign which defeated the government’s attempts, via referenda, to introduce military conscription during World War I.

The development of Irish consciousness in Australia passed through several stages beginning with the convict period. Over 40,000 convicts were sent to Australia directly from Ireland. Most of these were ordinary criminals, but the association of a minority with the 1798 Irish rebellion, and subsequent disturbances, gave them the reputation of being seditious rebels. This image was heightened by the association of the Irish convicts with the Castle Hill rising.

By 1810, however, many emancipated Irish convicts were settling on land grants and becoming reasonably prosperous: from 1820 they were able to practice their Catholic religion, whose freedom and public status became a cause around which they rallied.

The 1830s to the 1870s brought an influx of Irish immigrants, which, though they were met by considerable hostility from establishment and Protestant quarters, led to significant concentrations of Irish settlements in both rural and urban areas.

It was not only the prospect of free land that attracted the Irish. From the 1850s to the 1890s the discovery of gold in various parts of Australia drew them like a magnet. They were a colorful, boisterous, and at times violent element in life in the gold fields, most obviously in the Eureka Stockade incident, which was seen as a cause of liberty and democracy against government tyranny.

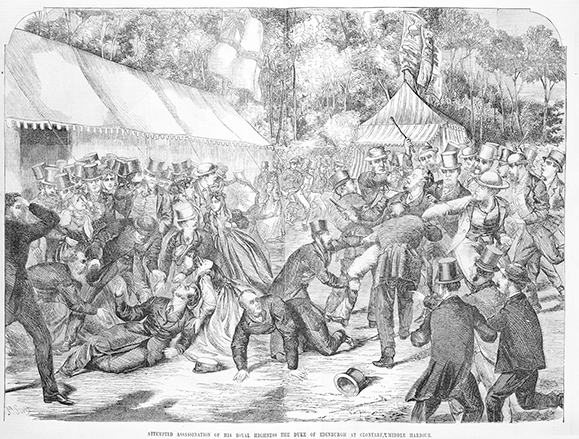

Some of these migrants were strongly assertive of their Irishness and various conflict situations developed, the most spectacular being the attempted assassination of the Duke of Edinburgh by an Irishman in Sydney in 1868. This was depicted as a Fenian plot, but in fact it was an isolated incident. The Australian Irish then, and later, were essentially loyal and law-abiding citizens and wished to be seen as such. But they also wished to have their own identity and character respected, and were not prepared to conform to pro-British ultra-loyalist pressures.

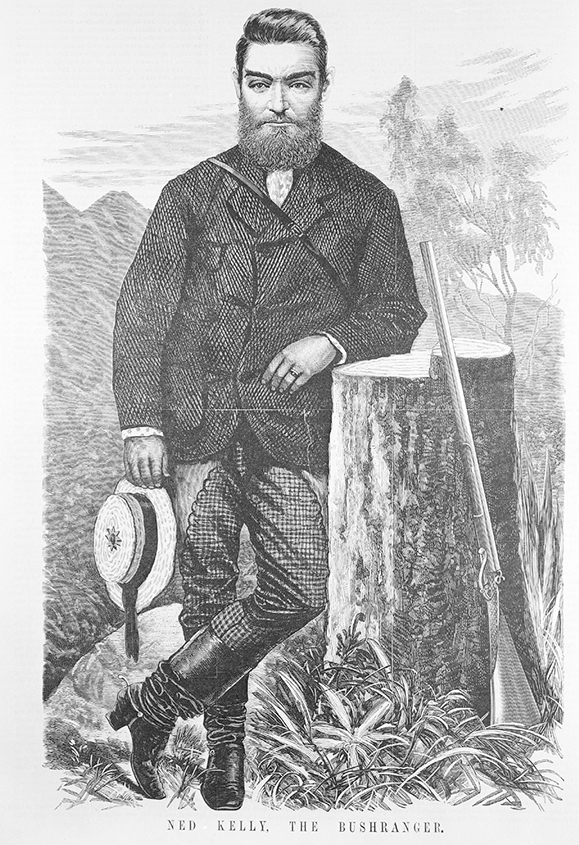

While the majority of Irish immigrants were reasonably successful, a few were less so. Ned Kelly and his mainly Irish-Australian gang menaced travelers in the Australian bush and held up gold coaches, claiming to represent the outrage of the deprived and oppressed Irish underdogs in the colony. Kelly continues to be a national folk hero.

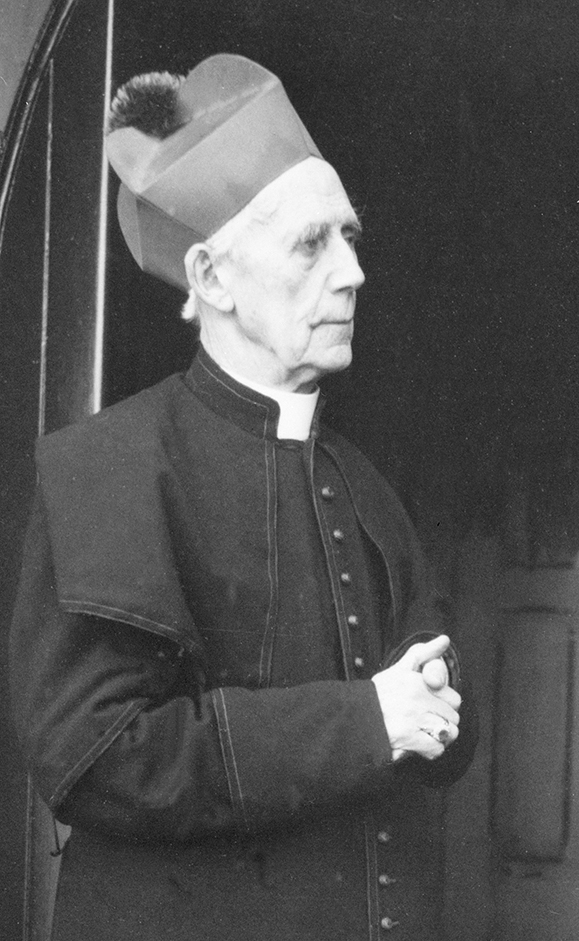

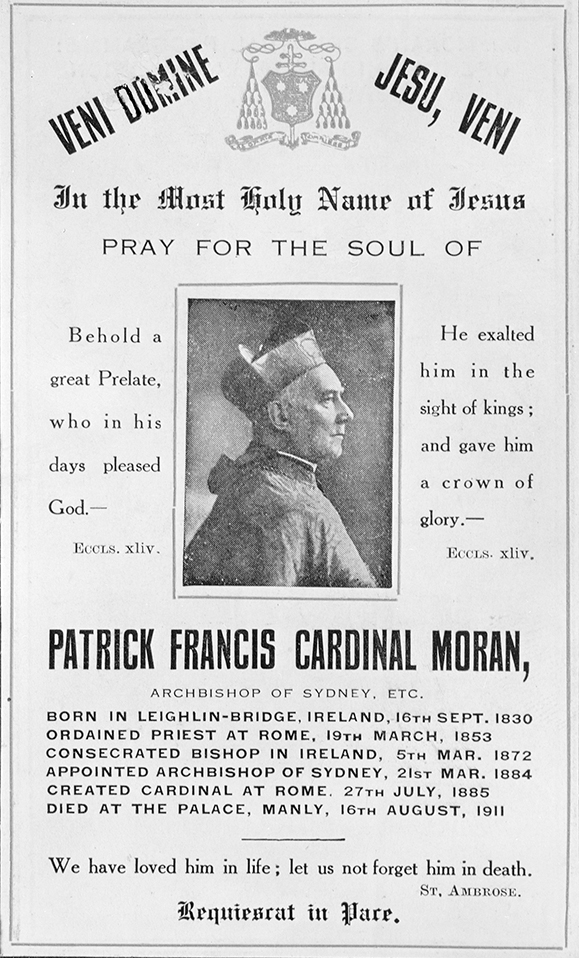

From the 1880s to the 1930s, Irish priests dominated the Catholic clergy under Cardinal Moran and Archbishop Mannix. Moran (1884-1911), experienced in the politics of the church in Ireland, saw Australia as a part of Ireland’s spiritual empire. He imposed unity on Irish organizations, took over the organization of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations, and sought to take up Irish matters in the highest levels of society and government.

Moran helped change the Irish-Australian image from one associated with the lower orders, to that of participation in the mainstream, at all levels. In this objective he had the assistance of a massive and expanding Catholic education system – compulsory for all Australian Catholics – staffed by the Irish religious teaching orders, of which the Christian Brothers and Sisters of Mercy were the most dominant. These schools taught the state syllabi, plus religion, and by excelling at public examinations, gave Irish Catholics access to the government service and the universities.

National folk hero Ned Kelly.

Susie O’Neill waves a kangaroo after winning a gold medal for the 200m freestyle at the Sydney Olympics.

The Irish clergy used the church to foster Irish culture in the interests of religion and self-advancement. This was paralleled outside the church by the popularity of the Irish Home Rule movement, which aimed at securing Ireland self-rule within the British Empire structure. In 1883, the Irish Parliamentary Party sent John and William Redmond to Australia to gain support and get funds. The enthusiasm and donations which greeted them and the subsequent visits of John Dillon, John Deasy and Sir Thomas Esmonde in 1889, and Michael Davitt in 1895, 1906 and 1911-12, indicated that the Australian Irish were prepared to give generously to support Irish political causes.

However, due to tyranny of distance they were committed to and involved in Ireland as a home place, as a culture, and as a sentiment, rather than concerned with Irish politics. At the time of the Famine it was five months before the news reached Australia. The response took nearly a year. Even in the age of steam, exchange of information was never under two months. The electric telegraph changed this eventually, but the Australian Irish felt themselves powerless and paralyzed by their remoteness. They interested themselves instead in local politics, and became largely identified with the new Labor party.

Archbishop Daniel Mannix of Melbourne presided over an Irish Catholic challenge to dominant pro-British Australian values in the period 1915-21. The Easter Rebellion in Dublin in 1916 and the two conscription referendums in Australia in 1916 and 1917 were the central events. In this period, events in Ireland captured the attention and sympathy of many Australians of Irish birth and descent, dividing them from the Australian establishment and political leadership, which saw the Irish rebellion against Britain as the height of treachery and disloyalty.

Conflict within Australia centered on the proposal to introduce war- time conscription, opposed prominently by Mannix and defeated in referenda. Tremendously popular with many Irish Catholics, the Archbishop’s championing of the cause of Irish independence led to continuous public conflict, not ended until Ireland received a degree of independence in 1921.

Mannix’ s anti-conscription stand made him a national icon, not only with Irish Catholics but with workers within the labor movement. His Irish republicanism, however (he was a friend of Irish politician Eamon de Valera and was feted in the United States on his way to Ireland in 1920), made him many enemies who feared his charismatic leadership. He was not allowed to land in Ireland, his ship being intercepted at sea by a British destroyer; in Britain he was forbidden to visit cities with large Irish populations.

The Irish Civil War of 1921-23 was seen by most Irish Australians as a bewildering embarrassment and began a period of disillusionment and disinterest. In November 1922 Bishop O’Farrell of Bathurst told an Irish friend: “You can form no idea of the depression and the humiliation in the sentiments of the Irish-Australian at the state of affairs in Ireland.” By 1923 he was writing, “No one wants to speak of the Irish question out here.” In August 1927 Bishop Barry of Tasmania wrote, “I am completely disillusioned. This is not the Ireland of my youth and my dreams.” From seeming to embody holiness and noble ideals, an Ireland divided by bloody civil war seemed best forgotten. For many, Ireland’s neutrality in World War II compounded the embarrassment.

When Eamon de Valera, briefly out of office, visited Australia in 1948, the welcome was cordial but the interest displayed in Ireland’s affairs narrow and ephemeral. The re-emergence, from 1968, of violence in Northern Ireland did little to alter this situation, though attracting sympathy. By 1981 the few activists for Irish causes in Australia tended to be immigrants from Northern Ireland.

The past twenty years has seen a complete reversal in Australian Irish images and consciousness, to such a degree that Bono, when visiting with U2 in 1993, remarked, “It’s good to be in a place where the Irish are truly in charge.” Today’s Irish Australians are tops in every field including such visible icons as actor Mel Gibson (whose films Braveheart and The Patriot clearly show his feelings about British colonialism), and gold-medal winning swimmer Susie O’Neill. And while emigration from Ireland to Australia has been small in numbers since the 1920s, the number of Irish visitors, backpackers and those on short-term visas has increased massively over the last twenty years — around 50,000 in Sydney’s Olympic year. One thing is for sure: any visitor from Ireland will be welcomed like long lost kin in an Australia very much conscious and proud of its Irish heritage. ♦

It is regretable that the British left such a distasteful sensation among the natives wherever they governed.