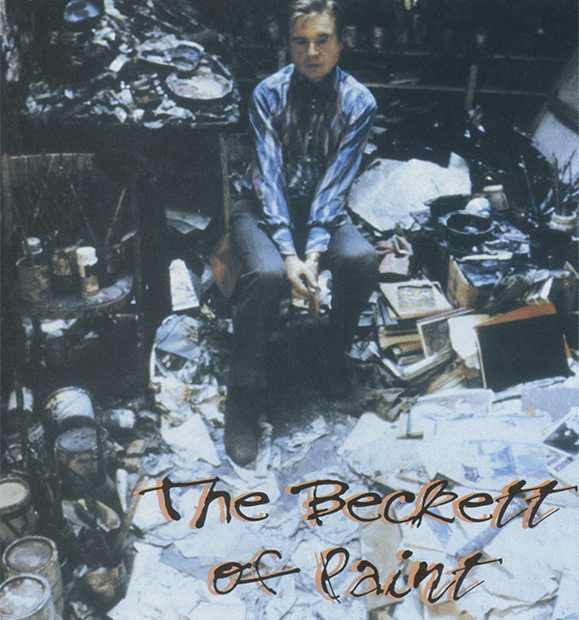

“I live, you might say, in gilded squalor,” Dublin-born painter Francis Bacon once remarked, explaining his attachment to 7 Reece Mews, the spartan twelve-by-eight-foot London flat that was both his home and studio for the last 30 years of his life.

For Bacon, the drab, confining space, accessed by a ship’s ladder, was more than just a place to hang his hat. With its paint-spattered walls, broken furniture and tables laden with rusting buckets of brushes adrift among a sea of trampled photographs and books, it was as much a work of an as his portraits.

“After all,” the artist who died in 1992 at the age of 83 said, “existence in a way is so banal, you may as well try and make a kind of grandeur of it rather than be nursed to oblivion.”

The studio and its contents, all 8,000 pieces of it, will become a permanent exhibition at Dublin’s Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery by May 2001. “It was an incredible coup for us,” Barbara Dawson, director of the Hugh Lane, says, smiling across a table piled with catalogues of Francis Bacon in Dublin.

The exhibition, which took place earlier this year, was curated by Bacon’s friend David Sylvester, and acted as a warm-up to the arrival of the studio. It was touted as the most important exhibition to come to the city in decades.

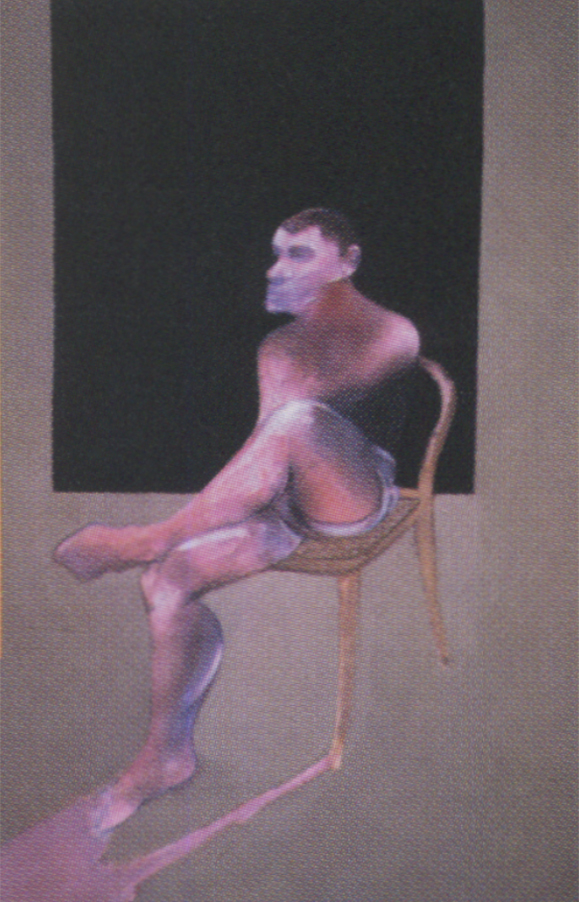

Bacon, who has been called the Beckett of paint, depicted the drama of human existence in his work. The often violent images of truncated bodies against a background of jeweled blue and marbled reds, lend themselves to numerous interpretations and emotions. No longer shocking – the reaction Bacon most wanted to elicit with his work – their majesty and painterly brilliance are more apparent than ever in their Dublin setting.

In Dawson’s office, the impression is more Matisse. Her pleated dress, the color of pomegranates, complements the sunflower yellow walls, as a compliant Irish sun streams steadily through the huge windows of what was once Charlemont House. Built in 1762 on such generous proportions that it earned for that part of Rutland, now Parnell Square, the title of Palace Row, the building, home to the Hugh Lane Gallery since 1933, is still the most remarkable feature of the north side of Dublin, which has remained resolutely unchic despite the advances of the technological tiger.

With the success of the Bacon exhibition and the acquisition of the studio, the gallery, funded by Dublin Corporation, is losing its backwater image and has gained points over its rival, the new Irish Museum of Modern Art at Kilmainham Royal Hospital.

The work of dismantling 7 Reece Mews began in 1998 with a pioneering team of 15 archeologists and conservators headed by Mary McGrath, a consultant art conservator for the gallery. Approaching the project as an archeological dig, they prepared detailed graphs of the studio and its contents, then covered the walls with a sealer before carefully cutting them out and dropping them into the garage below. The next task, undertaken by Dr. Margarita Cappock and a team of three art historians, was to catalogue all 8,000 items in the studio. Among the voluminous clutter were the familiar sources used by Bacon, the books on mouth diseases and radiology, John Deakin’s photographs of Bacon’s friends and the subjects of his portraits.

But much that is new also surfaced. “We’ve discovered one very important painting that was thought to have been destroyed,” Dr. Cappock said, the four walls of her office pigeonholed with the contents of the studio. “And some overpainted images, showing how Bacon worked out his ideas on the actual source for his work. This is going to give an entirely different perspective.”

Like a giant three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, the studio and its mayhem will next be reassembled by Cappock and Ryan in one of the gallery’s rooms, only the more fragile items being kept out.

All this hoopla could be taking place across the water at the Tare Gallery in London. John Edwards, Bacon’s heir and the man he looked upon as his son, first offered the studio to the Tate. The gallery dithered – and not for the first time. “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.” painted in 1944, established Bacon’s importance on the international art scene. But in 1952, when Eric Hall, the artist’s former lover and mentor, offered a painting to the gallery they had to be browbeaten into accepting it.

“It was an accident of chance – they just dropped the ball,” Dawson says, sidestepping the invitation to gloat, and echoing one of Bacon’s creeds in art and in life, his devotion to chance. It was also chance that put her in touch with John Edwards. “A friend of mine in London introduced me to Brian Clarke who is now executor of the estate, and he introduced me to Edwards.

“The studio had been offered to the Tare Gallery, but there hadn’t been much communication,” she delicately puts it, adding, “So they thought it would be better if it was brought to Dublin.”

(Last year the High Court in London removed the existing executors of the Bacon estate and named Brian Clarke as sole executor. As things stand, it may be a matter of some relief that the studio has found a home, since the estate is now engaged in legal action against Marlborough Fine Art, the gallery that represented Bacon for over 30 years, claiming they bilked him out of millions.)

“There’s nothing more depressing than the dusty saddle in the hall,” Bacon said, summing up a childhood spent in a series of big houses in and around the Curragh in Kildare where his father was an unsuccessful horse trainer. While he lived for a large part of his childhood in Ireland, no one, least of all Bacon, ever claimed him as an Irish artist. Undeniably though, his childhood experiences in combination with a powerful imagination shaped the artist he became.

Born at 63 Baggot Street, Dublin, in 1909, to Eddy Bacon, a querulous ex-British Army captain and his young stainless steel heiress, Francis was one of five children, spottily educated, who spent their time being shunted between England and Ireland by their restless parents. In Ireland they settled first in Cannycourt House near Kilcullen, where Bacon’s lifelong chronic asthmatic condition, worsened by his proximity to horses and hounds, first became apparent.

When guerrilla warfare broke out in Ireland in 1919 the family were under constant threat of attack. By now they were living at Farmleigh House, the former home of Bacon’s maternal grandmother whose third husband was the chief of police, a connection that further endangered the family’s safety. The Bacon household, however, survived the War of Independence intact perhaps because, as Bacon’s sister Ianthe believed, their head groomsman who was in the IRA was very fond of the Bacon children.

Still, the atmosphere of tension that pervaded his childhood, the constant fear of annihilation and the notion of being among people who considered him the enemy, shaped Bacon’s view of the world and his sense of being an outsider. His isolation was compounded by his burgeoning homosexuality and his father’s antagonism. According to Bacon, his father frequently had him horsewhipped by the groomsmen in hopes of making his son more manly.

Caught in the act of trying on his mother’s underwear, Bacon was banished at age 16 from the household and fled to London. Contrary to accounts by Bacon, Who was fond of injecting his life story with the same high tension he produced in his painting, he did, in fact, return to Ireland from time to time to see his family, but with the advent of de Valera’s government in 1931, the Bacon family left Ireland for good and there was nothing for him to return to.

“I have nothing in common with the Irish except perhaps a desperate cheerfulness,” Bacon said at the end of his life. Maybe there’s more to it than that. Of the exhibition he curated at the Hugh Lane Gallery, David Sylvester had this to say: “In Dublin, in these neo-classical rooms, the pictures look wonderful, they look like their true selves. Seeing them here it’s as if he has come home.” ♦

Leave a Reply