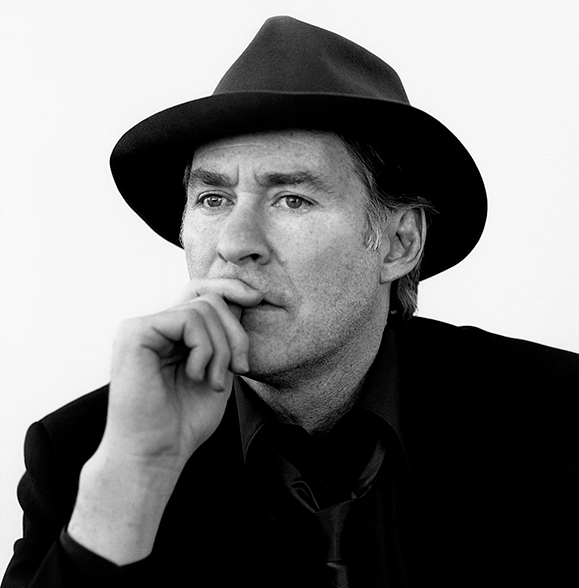

Kevin Kline is seriously funny. Blame it on his Irish side.

Settling back into a plush maroon velvet banquette in the restaurant of the Mark Hotel on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Kline sips his cappuccino, then leans forward in a conspiratorial fashion and smiles. “She was definitely in charge.”

Agnes Kline, his mother, was of Irish descent and a Catholic, and Robert, his father, was Jewish. Since Kevin had attended an all-male Catholic prep school, the St. Louis Priory, while growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, one might assume that Robert had lovingly deferred to his wife’s wishes throughout their 55-year marriage.

“Deferred?” Kline asks incredulously. “Well, that’s a nice word for it. My father cowered, is what he did,” he laughs. “We all deferred to my mother.

“She was a very powerful woman. She was very nurturing and loving but she could also be angry and tormented. That was the Irish in her. You know what they say about the Irish – they would rather fight than win.”

Although it was in 1978 that Kevin Kline leapt to stardom in the Broadway hit musical, On the Twentieth Century, it was his film debut, starring with Meryl Streep in Sophie’s Choice in 1982, that first aroused the media’s fascination with Kline’s background.

“I did an interview with the New York Times and it came out that my mother was Catholic and my father was Jewish, something that hitherto seemed just sort of incidental to me and not of great import.”

However, as trifling as his mixed background seemed to him then, Kevin admits, “I’ll probably be trying to work out which genes to attribute to my best and worst traits for the rest of my life. In fact, after this interview for Irish America, l have to rush off for another one with the Jewish Light,” he jokes.

“My mother’s father was from County Louth in Ireland. A lout from Louth,” he quips. “His name was Delaney, which is my middle name. My grandmother, his wife, was also from Ireland. Her maiden name was Kirk,” Kevin explains.

“My grandfather was a tavern keeper in St. Louis during prohibition,” he says smilingly, “so try and Figure that one out.” Kevin becomes serious. “It’s a bit sketchy because my grandfather died when my mother was only six years old, so she didn’t know him very well.” Kevin’s mother knew tough times as a child, growing up with five siblings and without a father, but she displayed a resilient and passionate character. Then, despite having been raised a Catholic and going to Mass every day, she still fell in love with and married a Jew. “It think it was music that brought my parents together,” Kline surmises. “They shared a passion for music. My grandmother didn’t go to their wedding, but that wasn’t because my father was Jewish, it was because he was – unimaginable and inexcusable – divorced!

“My father wasn’t at all religious.” Kline continues. “He was somewhere between an agnostic and a pantheist. In fact, he used to come with us to Mass and just sit there. He believed that Jesus was an interesting fellow who had a lot of good things to say. My father would say, `I’m not sure that he was the Son of God, but I do think he was a great leader and a great thinker.’ But as far as going to church nowadays, I feel that having gone to a Catholic school and attending Mass every day for six years has me covered for a lot of Sundays.” Kevin smiles. “Actually, I still go to Midnight Mass occasionally and Easter services.”

Kline’s acting genes came from both parents. “For years I thought it must be my father because, in his youth, he wanted to be an opera singer; he played the piano and he sang. There was always music in our house.

“But,” Kevin continues, “it was really my mother who was the genuinely histrionic one. She was the drama queen, very outspoken, very reactive, a complete character for the occasion, every occasion. It’s funny, only recently a friend of mine was looking at our wedding pictures and asked `Who is that old actress? I remember that face. She’s famous, who is she?’ I had to tell him, `That’s my mother,'” Kevin laughs.

The music-drama split runs through Kevin’s veins and destiny. “Although I always loved drama, my real ambition was to conduct and compose music,” he reflects. Indeed, Kevin pursued his ambition by studying music for his first two years at the University of Indiana before switching to drama studies and earning a degree in speech and theater.

Why the change? “I found sitting in a practice room for hours a very lonely activity” Kline answers. “But the truth is, if I’d practiced my Bach more seriously as a child I might be a musician today. When I reached college I found I was way behind the other students who’d taken the whole thing seriously from the age of five. The realization sunk in that, while l was hammering away for all I was worth, l would end up being a mediocre musician.”

That attitude reveals the key to Kevin Kline’s success as an actor. Mediocrity is not, and never was, acceptable. “My mother had the highest expectations for all four of her children,” he remembers. “She was full of Irish sayings like `If you live like a horse all you will get is grass.’ What she meant was that you must aim high. However, when need be, she’d soften a bit, saying things like `Oh, well, grades aren’t all that important, Einstein never did get a good report card.’ Alas, you just knew that she was dying inside if you brought home a C or a D.”

It wasn’t just at home that Kline’s intellect was challenged. In most prep schools while pupils are preparing a nice production of As You Like It for their end of year effort, Kevin’s Benedictine monk headmaster tossed out a far more daunting recommendation. “He blithely suggested we put on a play written in 184 B.C. by the early Roman comedy dramatist Titus Maccius Plautus and thought that we ought to do the whole thing in Latin!

“We managed to convince him that a bit of the subtle comedy might be lost on our audience with their questionable grasp of the language.” Kline reflects, “The Benedictines were great educators; this was a classic facility. I was not a great student, I was too easily distracted, but I got a good education in spite of myself.

“I learned the things I liked. I loved languages. I speak French, Italian and Latin although I don’t exactly pore over archaic Latin texts. Mathematics and the sciences, other than biology, eluded me completely.

“Maybe that’s the Irish in me, that love for words.”

After graduating from college Kline moved to New York and enrolled in the first drama class that producer/director John Houseman formed at Juilliard, a school primarily celebrated for its music curriculum, but now also renowned as a drama school. “I remember studying the character of the Russian people for a play I was in,” he recalls. “The director told us that Russians have these enormous mood swings – going from unbridled joy to the very depths of despair. Then we did an Irish play, The Hostage by Brendan Behan, and another director told us that the Irish have these enormous mood swings, they go from unbridled joy,” Kline laughs, “to the depths of despair.”

Upon graduating from Juilliard, Kline along with fellow actors, including Patti LuPone, became founding members of Houseman’s new professional group, The Acting Company. “It was a great way to launch a career,” enthuses Kline. “We were touring primarily, then doing four-week runs in New York. I was playing marvelous roles in Shakespeare, Chekhov, and Marlowe,” he continues happily. “The gypsy life was fabulous!”

Kline left the company in the mid-70’s, to face the grim reality of life as an independent actor. “I was offered a part in the musical, On the Twentieth Century,” he recalls “but, at first, I turned it down. I’d been playing leading roles and thought the part was too small for me.”

Turning down an opportunity to be in a musical by the legendary Cy Coleman and to be directed by Hal Prince, might seem a pretty bizarre thing to do. “I was actually returning the script to Hal Prince’s casting director, Joanna Merlin, when she persuaded me to take the part, thank God. It was my big break, it really put me on the map.”

Of those days Cy Coleman recalls, “Kline’s part started out small but he was remarkable. He blew us all away. He’d come into rehearsal every day with ten different suggestions on how Prince should direct him.” Recalls Cy, “He was so great looking, so physical and so inventive. He was actually climbing the walls and hanging by his feet,” he laughs.

“His part grew in leaps and bounds. We finally gave him a number of his own. He stole the show.”

“Yes,” agrees Kevin, “I had to come up with all these idiotic acrobatics.

“Well, that’s the Irish in me, I was desperate. I hadn’t worked in nine months, and I was determined to make something of this.” What he made of it was a 1978 Tony Award-winning performance.

As Cy Coleman sees it, “Like other great artists that I’ve come across, Kevin was completely focused, he had a great intensity and could pinpoint exactly what he wanted. He used to meditate before every performance. Basically, he seemed to me a sort of inward person who let it all out on stage.”

Hearing this appraisal, Kevin seems surprised. “That’s funny, I’ve always felt completely unfocused. In fact, I find myself going to bed at night with ten books under my arms. I jump from one to another. I think of that as an Irish thing or maybe it’s a Jewish thing.” He manages to look mildly confused. “There is so much to learn and so little time. I feel huge gaps in my knowledge of history and literature. I was a bit of a goof-off during my academic years and I’m paying the price for that now. You know, when I beat up on myself, it seems like a really Irish thing.” He clowns around and adopts a brogue, “Ah, the shame, the f—- shame.

“I hardly feel focused, but it’s true I do meditate. It was something I learned to do to discipline myself when we were touring in rep. It gave me energy, and relaxation, and – yes, I guess – focus.

“When I work, especially in a physical comedy, I guess I do literally bounce off the walls. It’s a manic sort of thing, really.” Has he ever felt close to madness? “Only during interviews,” Kline responds with a crazed look in his eye. “No,” he continues seriously, “though I do feel as though I’m skittering on the edge of madness most of the time. I see the outrageous possibilities in just about any situation.”

And is this the part of Kevin Kline that allows him to express himself as a comedic actor?

“It’s the part of me that wants to do something utterly inappropriate, to do or say something really shocking, absurd, silly, even childish,” he admits. “That’s probably why I’ve always loved the Pythons.”

When Kevin saw the British comedy team Monty Python’s Flying Circus in their first film, And Now for Something Completely Different, he was knocked out. “I thought, who are these people? They are doing this just for me,” he laughs.

“It was a very private feeling, I just felt connected with them immediately. It was like a beacon of silliness that shone right on me and I just loved them.

“Then when they started showing them on TV on PBS, I watched them religiously every Sunday night. That was in place of going to church, I suppose,” he adds whimsically.

By the mid-80’s, having notched up his second Tony Award for The Pirates of Penzance (1981), Kline followed up his success in Sophie’s Choice with another hit movie, The Big Chill, playing alongside Glenn Close and William Hurt.

Although he now was very much in demand in Hollywood, he strangely shunned the roles that might have led to superstar status. “I can only do what really interests me,” reasons Kevin. “That is why I accepted the role of Otto in A Fish Called Wanda although people warned me against doing it. They said, `The humor is too English, it won’t work in the States so it won’t help your career.’

Otto wins an Oscar: Kline receives an Academy Award for his role in A Fish Called Wanda

Kline plays a Brooklyn Jew in Sophie’s Choice.

“I didn’t care if it didn’t work,” he insists. “Just to have the opportunity of playing alongside John Cleese and Michael Palin, whom I consider two of the funniest guys in the world, was enough for me.”

Not only did A Fish Called Wanda (1988) have a very positive effect on Kline’s career – he won an Oscar for his role – but it also proved to be a psychological breakthrough prompting him to change his whole attitude towards his craft.

“It was such a wonderful experience for me because, while I’d acted in numerous comedy roles on stage, I had never done a strictly comic role on film, let alone one actually written for me. When Cleese and I were working together on the western Silverado, John saw me goofing around in rehearsals, and then getting very serious when the camera rolled. One day John said to me, `I had no idea you were so silly,’ and then went on to create a part in his forthcoming film where I could be as silly and outrageous as I pleased. This turned out to be the part of Otto, a character John claims he loosely based on Gordon Liddy, the former FBI agent who was such a central figure in the Watergate scandal.

“It’s funny, but only about a week ago I found an old T-shirt that John had had made up for me while we were shooting Wanda. It says `Who Am I?’ because hardly a day of shooting would go by without my asking about my character, `Who is this guy?’ There seemed to me to be something so illogical about Otto; he was completely brain-dead stupid but then he could crack a safe, scale tall buildings and do seemingly impossible feats.

“Then Cleese developed this idea that Otto read and quoted Nietzsche but invariably got it all wrong. Now, that,” he explains, “really shows John’s true genius, to be able to create a comic character who had such outrageous contradictions and not just he the usual one-dimensional figure.”

Kline’s mental shift in acting technique came when “John told me to break all the rules. Up until then, during the five or six movies I’d made, I’d had to contain all those silly impulses, and now here was John saying to me `Appall yourself, see how broad, how cheap and how far you can go doing what you think is genuinely funny!’ and that is just what I did,” he announces proudly.

“I broke all the rules I had had instilled in me in acting school and by other directors. I had already started to break all these rules on stage, but I was afraid to do it on film. You see, I thought film acting was only about underplaying, but John showed me that if something is full and real it really doesn’t matter how big it gets,” he adds excitedly; “the camera and the screen can contain it.

“For years I had labored under the delusion that everything I had learned about stage acting was somehow not applicable to films, and I realized that I had in fact imposed an idiotic restraint on myself.” He concludes, “The fact is that acting is acting.”

During the 1990’s Kline scored financially and critically in Dave (playing a dual role as the U.S. President and his doppel-ganger), French Kiss (a romantic comedy, opposite Meg Ryan), In and Out (another comedy), and The Ice Storm (a more serious drama). He also starred with Michelle Pfeiffer and Rupert Everett in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream before teaming up with Will Smith in Wild, Wild West.

Where would he rather be performing – stage or cinema? “It’s not that I’m longing to be back on stage. What I long for is the material that the stage provides,” he admits.

“My favorite playwrights are Shakespeare and Chekhov, and I love Eugene O’Neill. In fact, when I saw A Moon for the Misbegotten recently, Gabriel Byrne just blew me away! I thought, God, this is what I’ve heard about for years, how film provides certain opportunities but the stage, especially the classics, does something else. I saw an actor there that I’ve never seen on film,” admits Kline. “In fact, I immediately called my agent to find out who was replacing Byrne but, alas, the play was just closing. Normally, I always refuse to replace anyone, but I was so enthralled by what I saw Gabriel Byrne bringing to the play, that I thought, God, I’d love to try my hand at that part, too.”

If Kline displays ego here, he shows humility when he describes the qualities in life he admires. “Ideas, originality and beauty certainly excite me. Also, athletic talent.

“I loved watching the young Russian gymnast Olga Korbut doing extraordinary things. And ballet dancers or anyone who does difficult physical things that require tremendous effort and concentration and, at the same time, restraint and discipline.

“I admire people who push into the beyond because most of the time the rest of us are mired in a limited realm and we see how finite and how sad our little lives are.

“But if you think about it, history is defined by those very people who have broken through and have done extraordinary things, people who refused to believe that their place was down here and said, `No, my place is up there.’ Those are the people who find cures for polio, win the Grand Slam in golf, or write the genuine masterpiece. Those are the ones who make real changes in the world, the martyrs who dedicate themselves to helping other people.

“What about talent?

“Well, of course, talent is a requisite, but it must be applied,” he reasons. “If I have a talent for acting, it was not that apparent at first. In fact, remember I was a music major at college and when I first started acting, my acting friends were quick to say, `You should really stick with the music.'”

As far as future goals in his career are concerned, Kline admits, “I’d love to play Lear and Falstaff on stage. And, in terms of European directors I’d love to work with the film director Bertrand Blier, he’s so insanely talented and outrageous.”

Any regrets at turning down a role? “Regret is too strong a word, but I sometimes wish I hadn’t turned down a meeting with Ron Howard who was interested in me doing the movie Splash. Tom Hanks ended up with the part and I thought it was a very charming movie.

“l never feel completely satisfied with what I’ve done. I tend to see things too critically. I’m trying to get over that. I’ve got the Jewish guilt and the Irish shame and it’s a hell of a job distinguishing which is which,” he laughs.

“Maybe it was because my parents were very proud of me but neither of them could ever quite figure out my success,” he recalls. “It was a few years after I’d made several movies when my mother, sounding astonished, told me, `We had a call from Mrs. Jones, across the street, who saw your movie and she just thinks you are her favorite actor and she really loved you and the film!’ So I said to my mother, `Why are you so astounded that someone in your family could actually be good at something? Stop sounding so f—— surprised!’

“They even walked out of one of my films,” Kevin recalls, even now sounding a bit shocked. “It was Grand Canyon. My Mom mentioned in a phone call that they were planning to go see the film. After that the matter didn’t come up in a few subsequent regular Sunday calls, so I finally broke down and asked point blank if they ever got to see it. `What did you think of it?’

“`Well,’ my mother kind of spluttered, `We saw it but we didn’t see all of it. We left. We just didn’t get it, it seemed kind of stupid.'” Kevin’s eyes widen. `Didn’t get it?’ I told her. `Jesus, never mind that you didn’t like it, I’m in it! Lie to me! Tell me you liked it. How can you walk out on a movie your own son is in?'” Kline laughs and then softens.

“The fact is Grand Canyon did have kind of a dreamlike quality, a phantasmagoric feel about it. Perhaps its poetic tone eluded them,” he reasons.

Reminding us that his parents’ artistic discriminations were the very reason for his own integrity and individuality, Kevin laughs and says, “Yes, that’s it, they were the source of my integrity, my neuroses, my mercurial swings from self-loathing to delusions of grandeur, but it’s that conditional love that makes you really psychotic. I could go off like a rocket at any minute!”

Kevin continues in a more serious vein, “What really saddened me about it was that implied provincial notion, shared with most people, `Well, anyone can act,’ and the real tragedy is that, in fact, it’s true. Models, athletes, journalists are all cast, and movies can make almost anyone look like an actor.”

Pursuing this line, Kline declares, “I believe in elitism. American culture is an oxymoron. I’d like to launch a campaign, `Elitism for Everyone!’ We are oversated with advertising slogans yelling `Go See the Number One Movie’ or `Tune in to the Number One TV Show.’ I’d like the pendulum to swing back the other way so that people would be influenced by an ad that quietly said: `Go see this film, everyone else hated it!'”

When asked about which film most affected him, Kline reflected, “Certain films touched my heart for various reasons. Sophie’s Choice moved me most. Not only because it was my first film but to work with Meryl Streep and Alan Pakula on that material, a film version of William Styron’s superb novel, was, in itself, remarkable.

“It was so intense, so exhilarating just to go to work every day, yet so difficult and frightening because it was my very first movie.”

Did Kevin feel any special identification with his character in Sophie’s Choice, a Brooklyn Jew. “No,” insists Kline, “because I never felt particularly Jewish. My father wasn’t religiously Jewish in any way, and I’d been brought up as a Catholic. In fact, I knew so little about the religion and the ethnic heritage, I had to do quite a bit of research into just what it meant to be a Jew living in Brooklyn in 1947.

“You see, Sophie’s Choice was all about guilt. The guilt of the survivor, Sophie, and about the guilt of the man who hadn’t participated, the outsider, in this particular case a schizophrenic Jew.”

It’s only now that he feels more of an affinity with his father’s heritage. “It’s funny, but living in New York, being in the theater, you become sort of an honorary Jew, whatever your background,” Kevin grins. “You start picking up certain Yiddishisms and eating lots of deli food.” Then, more seriously, he adds, “I’ve become very fond of the religion and I’ve begun to study it closely.”

Kevin lives in New York with his wife, actress Phoebe Cates, whom he married in 1989, and their two children. “Phoebe’s father, the late producer Joe Cates, was Jewish and her mother, like mine, was a Catholic. We’re bringing up the children a little Catholic and a little Jewish,” he says, “so they can decide for themselves what they want to accept when they are older. They are so young that, right now, to them I’m God, and I’d hate to disabuse them of that notion.”

Speaking proudly of his beautiful wife, they starred together in Princess Caraboo in 1994. Kline says, “Phoebe is very musical, in fact she had a recording contract with Columbia Records but she sort of lost interest in that. However, our son is studying the piano and the clarinet and our daughter piano and violin.

“I’ve even had the opportunity of fulfilling my fantasy of conducting an orchestra,” he says excitedly. “Skitch Henderson has invited me to conduct the New York Pops three times at Carnegie Hall! Now, how’s that for a cheap misuse of celebrity?”

As far as celebrity is concerned, Kevin admits, “At first I was very self-conscious about being noticed or stared at like a zoo animal, but now I don’t notice it. I sort of walk around in my own bubble,” he laughs.

“I love going to the Knicks games and there is sort of an American kind of familiarity where someone will yell out, `Hey, Kevin, I guess you’re tired of hearing this, but I really loved your last movie.’ I don’t resent this, it’s nice,” he admits.

“Maybe there is something wrong with me, but I never tire of hearing a compliment, that I have given people some pleasure. It’s really important, since my kind of work requires an audience to complete it. If you’re getting through to people in some way, making them feel something, or making them think a little, that’s really quite satisfying.

“Because so much of life is dehumanizing, I think that one of the functions of art is to remind us of our humanity and to bring it all back into focus.” Kevin adds cheerily, “I’m glad I’m part of that process, but it’s also so sad, in a way. It’s sad that it’s the only thing that I have any gift for. There’s the Irish in me again.” Reminded that he has also shown a lot of courage in his career, he firmly resists. “No, being brave in life means risking everything, and I never have done that.” He glances at his watch and, seizing a large brown envelope from the table, leaps up and says, “Oh, I must go. I have a meeting about my first film directing project.” He grins. “Now, that is something that for me is quite daring and bold. That’s where you risk everything!” ♦

Leave a Reply