Ethnic casting issues in movies.

Our moviegoing experience would be much diminished if we had never had the chance to see Liam Neeson as Oskar Schindler, Peter O’Toole as Lawrence of Arabia, Greer Garson as Mrs. Miniver, Pierce Brosnan as James Bond, or Kenneth Branagh as Henry V. We would have been equally impoverished if we had not seen Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind, Maggie Smith in the starring role of The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, Daniel Day-Lewis as Christy Brown in My Left Foot, or Alan Rickman as Eamon de Valera in Michael Collins.

The actors in the first list are Irish-born but created memorable characters of different ethnic backgrounds, from the German businessman who rescues Jews in Schindler’s List to the quintessential British secret agent in three James Bond movies. The second list is comprised of non-Irish actors who have given equally splendid performances in Irish roles. But if some purists had their way, all such castings would be discouraged.

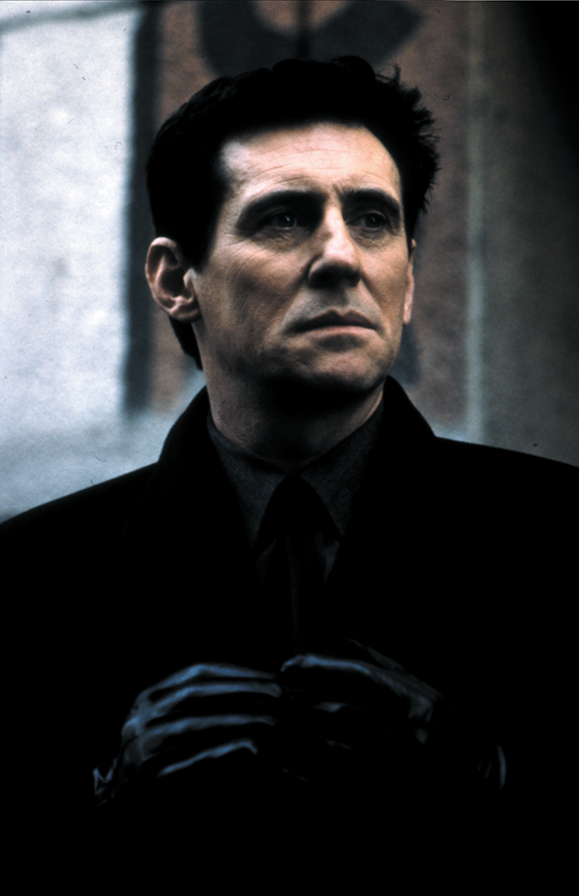

When Irish actor Gabriel Byrne was profiled in the February/March 2000 issue of Irish America, he provocatively raised the issue of appropriate ethnic casting, focusing attention on what he considered the inauthenticity of last year’s film version of Angela’s Ashes:

“I’m tired of English and American actors playing Irish roles, because the reverse is not true. There are a lot of really brilliant Irish actors and actresses that never get a chance to do anything. Frank McCourt wrote a brilliant book that deservedly became a worldwide phenomenon. But is it fair to say that it’s an Irish movie? An Englishman — Alan Parker — directs it. It’s financed outside Ireland. The screenplay is by an American writer [Laura Jones, who wrote it with Parker]. It’s produced by an American [actually it’s by two Americans, Scott Rudin and David Brown, as well as Parker]. It has a Scottish actor [Robert Carlyle] playing the role of the father, an English actress [Emily Watson] playing the mother. Why could they not have made it with an Irish actor, an Irish actress, and an Irish director?”

Byrne is a fine and versatile actor, and I am personally indebted to him because he came to my defense during the Patriot Games controversy in 1992. When my negative review of that virulently anti-Irish film was publicly attacked by my own editor at Daily Variety, Byrne wrote me a letter of support. I didn’t know it at the time, however, because the letter he mailed to Daily Variety somehow never reached my desk. Byrne’s fierce involvement in cultural and political issues befits his passionate involvement in his actor’s art.

So if I disagree with Byrne on this issue, I do so with respect and with appreciation of his concern for the integrity of Irish culture. This is one of those issues with two sides that don’t cancel each other out but instead recall the wisdom of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s dictum, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in the mind at the same time and yet still maintain the ability to function.”

Those who contend that only Irish actors should play Irish characters must accept the unwelcome corollary, that Irish actors should be restricted to Irish roles. Only recently has this issue emerged, accompanying a general rise in Irish pride and ethnic consciousness both in Ireland and among the Irish Diaspora. But long before “political correctness” became conservative code for attacking liberalism and its demands of equal opportunity for all citizens, there had been similar controversy over the miscasting of characters from other minority groups, especially African-Americans and Native Americans.

In the early days of American films, black characters were not played by black people but by white actors in blackface, following a tradition established in minstrel shows. D. W. Griffith’s groundbreaking but racially infamous 1915 film The Birth of a Nation cast a white actor, Walter Long, as the would-be rapist Gus, one of its black villains. To contemporary eyes, that bizarre casting makes plain the true subtext of The Birth of a Nation, that the sexual and racial anxieties and prejudices of Caucasians tend to be projected onto African-Americans.

It’s a measure of how segregated Hollywood was in 1950 that when Sidney Poitier first set foot on the Twentieth Century-Fox lot, the only other black person there was the man who shined shoes. African-American actors have made considerable strides since then but they still have far to go, as Spike Lee makes clear in his new film Bamboozled, a satire of racism in the television industry. Damon Wayans, playing the only person of color working for a fledgling network, comes up with a hit series sending up racial stereotypes in outrageous fashion, Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show.

Casting whites as Indians is among the most glaring flaws of old Hollywood movies. Among the most egregious examples are Don Ameche in Ramona, Robert Taylor in Devil’s Doorway, Burt Lancaster in Apache, and Katharine Ross in Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here. Eventually a few authentic Indian actors were given chances to play Indian roles, including Chief Dan George in Little Big Man and Graham Greene in Dances With Wolves, but those parts unfortunately still stand out as novelties. Real Indians hired as bit players in Hollywood Westerns sometimes compensated by mischievously making obscene comments when asked to speak their own language on screen.

African-Americans and Indians were not alone in being insulted by moviemakers, as was demonstrated by such notorious miscastings as John Wayne as Genghis Khan in The Conqueror, Mickey Rooney as a Japanese in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Alec Guinness as the Indian Professor Godbole in A Passage to India (a casting choice Guinness considered “absolute madness”), and Katharine Hepburn as a Chinese in Dragon Seed and a Russian in The Iron Petticoat. Hepburn asks Bob Hope in The Iron Petticoat, “Vy you are smilink?”

What is known in the theater as “non-traditional casting” – giving minority actors roles written for other races – is a more complicated issue in movies. Most movies present themselves as realistic rather than stylized portrayals of the world. Today few people would accept a white actor playing a black character, with the possible exception of a classical role such as Shakespeare’s Othello, the Moor of Venice, who has been portrayed on screen by such Caucasian actors as Orson Welles and Laurence Olivier, whose 1965 film performance went way over the top with its blackface makeup and exaggerated ethnic mannerisms; Welles told me that Olivier’s Othello reminded him of Sammy Davis, Jr. The most recent screen Othello was the African-American actor Laurence Fishburne in 1995.

Women were not allowed to appear on stage in Shakespeare’s day, so men played the women’s roles. Eventually women were able to assume male as well as female parts in Shakespeare plays; most famously, Sarah Bernhardt played Hamlet on both stage and screen. Women traditionally have played James M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, including Betty Bronson in the silent film version, Jean Arthur on Broadway, and Mary Martin on both stage and television. Katharine Hepburn disguised herself as a boy in George Cukor’s deliciously daring Sylvia Scarlett (1936), and Linda Hunt won an Oscar for playing a man in The Year of Living Dangerously (1983). Men often have masqueraded as women in movies, mostly in farces, such as Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis in Billy Wilder’s 1959 masterpiece Some Like it Hot. Male actor Jaye Davidson played a groundbreaking transsexual role opposite Irish actor Stephen Rea in Neil Jordan’s 1992 film The Crying Game.

During the heyday of the Hollywood studio system and beyond, it was an accepted convention that American-born actors would play people from other countries, often including Ireland. Such complacency occasionally backfired. It’s no accident that Parnell (1937) was the biggest flop of Clark Gable’s career. Ryan O’Neal seemed too indelibly American in the title role of an Irish rogue in Stanley Kubrick’s film version of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon (1975).

Three English actors (Sarah Miles, Trevor Howard, and John Mills) and two Americans (Robert Mitchum and Christopher Jones) filled the principal roles of David Lean’s unsuccessful Irish extravaganza Ryan’s Daughter (1970). That film’s critical and box-office disappointment was due more to its overblown romanticism than to its casting. Howard and Mitchum are particularly fine in their roles, but today such casting would not be so automatically accepted. As recently as 1992, Ron Howard’s Irish immigrant saga Far and Away was marred by the stage-Irish performance of American superstar Tom Cruise. In her essay “No More Blarney: Understanding the Irish Through Movies” for my Book of Movie Lists, the native Irishwoman Ruth O’Hara points out, “Cruise’s wife, Nicole Kidman, has a more than credible rural Irish accent in the movie; however, it’s a totally inappropriate accent for the daughter of landed gentry.”

With the recent upsurge in world interest in Irish culture and the flowering of the Irish film industry, Irish actors have become increasingly prominent on the international film scene. Neeson, Brosnan, Branagh, and Byrne are names big enough to carry a Hollywood production, and such character actors as Richard Harris, Colm Meaney, Stephen Rea, and Brenda Fricker are in demand for roles in international films. But many fine Irish actors and actresses still have not managed to make such breakthroughs.

Byrne’s objection to casting non-Irish people in Irish roles seemed to be directed primarily at international films rather than at indigenous Irish films that may or may not find an international audience. While it’s important to encourage a purely indigenous Irish film industry, the difficulty those films often have in finding a wider audience is a separate issue and a problem shared by all non-Hollywood films that do not use international stars. It’s a chicken-or-egg situation to some extent, since the only way to become an international star is to be seen by a world audience. And even Fricker’s best supporting actress Oscar for My Left Foot has not led to roles of comparable quality.

Adding Meryl Streep to the cast of Dancing at Lughnasa may have helped that film receive wider distribution, but it can be argued that her personality as an American star who plays a wide range of elegantly accented characters watered down the authenticity of Dancing at Lughnasa, an objection that cannot be made against British character actor Michael Gambon’s beautifully nuanced performance in the same film. Certainly Julia Roberts’s presence opposite Liam Neeson in Michael Collins, as Collins’s Irish lover Kitty Kiernan, seriously hurt that film because she seemed so glaringly out of place and was unable to summon up the craft to make herself believable. Anjelica Huston’s casting herself in the title role of her film Agnes Browne, based on Brendan O’Carroll’s novel The Mammy, also stirred some controversy, but Huston has a solid claim to Irish authenticity. Although born in California, she grew up largely on the estate of her father, director John Huston, in County Galway. I’m glad no one discouraged her father from casting Anjelica as the Galway-bred Gretta Conroy in his last film, The Dead (1987), based on the classic short story by James Joyce.

Gabriel Byrne’s complaint about inauthentic ethnic casting seems further qualified by the circumstances of his own career. His roles include the Italians Christopher Columbus and Vittorio Mussolini in 1985 TV movies; the German-American Professor Friedrich Bhaer in Little Women; and the Polish-American baker Bolek Pzoniak in Polish Wedding. Byrne also has played such prominent British characters as Lord Byron in Ken Russell’s Gothic and the loyal knight Sir Lionel in the animated film Quest for Camelot (in which Brosnan does the voice of King Arthur). Byrne even incarnated Satan in End of Days, for which he was careful not to use an Irish accent.

No one, presumably, would object to a versatile actor like Byrne playing a multinational gallery of characters. Ruth O’Hara praises Byrne as “most convincing” in his “scholarly but passionate” role as Professor Bhaer. Part of what keeps Irish and British actors in demand is their classical training and their resulting facility with accents, which helped Neeson win the role of Schindler over such American stars as Warren Beatty and Kevin Costner and enabled Emily Watson to play a working-class American woman so believably in Cradle Will Rock.

While I’m glad we didn’t see Costner as Schindler or Michael Collins, another role he coveted, my primary criterion for casting is simply whether the actor fits the part, regardless of his or her national origin. I would hate to impose rigid rules on casting, because a good actor should be able to play the widest possible range of roles, and filmmakers should be free to roam far from the beaten path in their casting choices.

Byrne does raise a valid concern about the high level of non-Irish involvement in the film of Angela’s Ashes. If it had been made with greater care for authenticity, and greater fidelity to the seriocomic tone of McCourt’s memoir, it probably would have reached a wider audience. Watson is a cipher in the thanklessly conceived role of the mother, one that an Irish actress might well have imbued with greater vitality and believability. But I found Robert Carlyle superb as the father, a character given more nuances than in the book. And the claim that a director should not be allowed to tackle subject matter outside his own ethnic group seems dangerously misguided, particularly since Alan Parker did a fine job with his 1991 film version of Roddy Doyle’s novel about working-class Dubliners forming a rock group inspired by black musicians, The Commitments.

Like Byrne objecting to Parker directing Angela’s Ashes, Spike Lee denounced Steven Spielberg for directing Amistad, a film about Africans rebelling against their captors on a slave ship. But Lee also has insisted that an African-American director should be able to make a film about Irish-American President John F. Kennedy, just as the white director Oliver Stone did with JFK. Therefore, by the same logic, a white director should not be barred from making a film about black history. Lee should not object to Stone making his proposed film about the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

It’s understandable that members of minority groups remain sensitive to the general pattern of the majority co-opting their histories. No one would quarrel with the appropriateness of Lee directing Malcolm X, and Irish director Neil Jordan probably did a better job with Michael Collins than a non-Irish filmmaker would have done, flawed though both of those films were. Nevertheless, it is always unfair, and dangerous, to advertise that “No [insert name of ethnic group] need apply.”

It would be wonderful if every ethnic group had greater access to the mass audience as actors, writers, directors, and producers. There still are far too few African-American and women directors. Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans are even more shamefully underrepresented as actors and directors. But the cause of diversity will not be served by a new brand of exclusionism. Such attitudes only tend to encourage the reluctance of studio executives to make films dealing with ethnic issues or controversial historical subjects. And ultimately it is the audience that suffers when creative artists are blocked or inhibited from expressing their talents to the fullest. So, bring on Daniel Day-Lewis as William Butler Yeats, Emily Watson as Kitty O’Shea, Brenda Fricker as Queen Victoria, and Gabriel Byrne as Tony Blair. ♦

Leave a Reply