How Sinn Féin’s Martin McGuinness is adjusting to his new role as Northern Ireland’s Minister for Education.

℘℘℘

Unusually for a politician, Martin McGuinness is early. He arrives at the Irish-speaking primary school in Newry, the Bunscoil an luir, as part of his duties as Minister for Education in the Northern Ireland Executive. The Executive, and McGuinness, are back to work after a several months’ suspension while the issue of IRA decommissioning was being worked out, and the children are excited about his visit.

The eight-year-olds don’t scream when he enters the small hall – he’s no rock star, but they know he’s famous and recognize him from TV. Dozens of tiny hands fly up when he asks the children if they have any questions. The first is from a little girl who wants to know if he’s been friends with Gerry Adams for a long time. McGuinness joins in the general laughter, and describes Adams as “a rascal, who goes on about birds and plants and trees,” but who “doesn’t know as much about them as he pretends.”

The truth is that McGuinness and Adams go back three decades. They were the youngest members of the Republican delegation secretly airlifted by the Royal Air Force to meet British government ministers in 1972 and for many years have steered the Republican movement away from war and into the peace process.

McGuinness’s Republican credentials and reputation are second to none. In 1973, when he was sentenced to six months in prison for IRA membership he declared to the Dublin court: “For over two years I was an officer in the Derry Brigade of the IRA. I am a member of the IRA and very, very proud of it.” He spent most of the next year in jail, again for being in the IRA. His reputation within the organization is rooted in his time as commanding officer of his native Derry Brigade from 1971 to 1973. The city’s center was virtually flattened by months and months of continual bombing.

McGuinness’s stature as a ruthlessly efficient leader stems from those early days of the conflict, and gives him a credibility with young IRA activists no one else – not even Adams – can match. He is also widely believed to have been IRA Chief of Staff from 1978 to 1982, and a 1988 U.S. Government report called Terrorist Group Profiles named him as the leader of the IRA. But there is little in his expression that hints of a violent past – his eyes are peaceful, his face cherubic.

His willingness to enter the Northern Ireland Executive convinced many Republican hardliners that the peace process is the way forward, and he appears to have made the adjustment from militant agitation to mainstream politics without great difficulty. Northern Ireland civil servants who were nervous about working with the IRA legend are said to be impressed at the commitment he has shown to his brief, and the Bunscoil children are delighted at his visit.

He is at ease with the children, and they are keen to shake his outstretched hand, but many of his answers are complicated and political, apparently aimed more at the civil servants who accompany him than the students.

“When I became Minister for Education some people from that section of the Unionist community who weren’t in favor of the Good Friday Agreement talked about my unsuitability because I left school when I was 15 years of age,” he tells the kids, and hints at his own difficult school days. “The vast majority of teachers at the school I was at were very, very good, but there were some teachers who were very angry people and some of them took it out on the pupils…I thought I might have liked to be a teacher but I didn’t stay on – I left because of the bad experiences.”

McGuinness failed the notorious Eleven-Plus exam, which is designed to divide children at the age of eleven into those with academic potential from those without, and to split them into different schools. With delicious irony, McGuinness is set to make a decision in the next few months on whether he will abolish, or keep, the dreaded exam.

This is exactly the sort of everyday, nonpartisan issue that makes at least some of McGuinness’s job appear like politics as usual. Many middle-class Protestant and Catholic parents are lining up to defend the advantages offered by the two-tier system to children who pass, and McGuinness is being heavily lobbied to retain the test. Although the Eleven-Plus issue cuts across the Nationalist/Unionist divide, many Protestant parents and teachers are uneasy with McGuinness’s power to make such far-reaching decisions.

“McGuinness’s political views are unacceptable – his history is unacceptable and he is unacceptable to the vast majority of folk from the community I work in,” said Glenn Reilly, principal of a Protestant high school in Limavady. “It’s a dilemma for many of us who believe in peace and power-sharing to have McGuinness held up as a role model for our children.

“But we’re at a stage where it’s becoming necessary to tolerate what’s unacceptable.”

Reilly’s school is no laager of ultra-Loyalism – it has close relations with the neighboring Catholic school, and the two even field joint soccer teams.

He sees McGuinness’s importance not in his long-term impact on the education system but in a more symbolic role – “he’s a caretaker to make the politically unpalatable taste a little more acceptable before someone else – maybe from a similar political tradition to his own – takes over,” he said.

Yet Reilly concedes that it’s preferable to have “someone local” as Education Minister, even someone like McGuinness, “who understands the psyche of Ulster people,” than an English politician.

“We would not invite McGuinness to visit our school,” said Reilly. “Too many parents would object. It’s too early, too controversial, there’s been too much hurt for people to find him acceptable yet.”

But as he tours the small Newry school McGuinness is relaxed and affable: this is, after all, friendly territory. The children banter with him about football, and he signs a school chair to mark his visit.

Later, in private, he opens up about his childhood and his time at the school run by Christian Brothers in Derry. “There was corporal punishment when I was there,” he said. “Some of these Christian Brothers were not a bit slow to use a belt or strap. I can’t say I was overly mistreated, everybody got it — there were very few who escaped. This was a minority of teachers. Most Christian Brothers were not in that mindset but there were one or two who were not suited psychologically for teaching.”

Discouraged, he left school. “I went immediately to work – my first wage packet was four pounds, twelve and six in old money,” he said.

McGuinness had hoped to be a mechanic, and applied for a job with a local garage. When he told them he’d gone to a Catholic school, his interview abruptly ended. He found work in a butcher’s shop, and was soon spending his spare time with other Bogside teenagers hurling bricks and petrol bombs at the police.

Despite his lack of formal education, McGuinness has focused on the minutiae of his department’s remit with impressive vigor – approving funding for two new religiously integrated schools, supervising Northern Ireland’s largest-ever school building program, and establishing a new body to promote Irish-medium education.

The school system McGuinness oversees not only has to deal with the peculiar issue of religious segregation – virtually all children attend a school that is either exclusively Protestant or exclusively Catholic – but also the more usual problems of shabby classrooms and a lack of resources, especially for children with special needs.

Temporary, portakabin-type buildings have sprung up in dozens of Northern Ireland schools in recent years. St. Brigid’s High School in Carnhill was built in the 1970s for 500 pupils but is struggling to accommodate an enrolment of over 900, and in Belfast the Dominican College has over 30 temporary classrooms to supplement existing accommodation that dates back to the 1800s.

In January, McGuinness took key senior officials to Washington, DC to meet U.S. Secretary of Education Richard Riley and hear how the Clinton administration has approached pre-school programs, special education, and technology issues. Riley, said McGuinness, has “taken a deep interest in the peace process and has offered considerable research to us done by his department on educational underachievement and other areas. He’s opened up the doors to my officials and we’ve built a very close relationship in a very short period.”

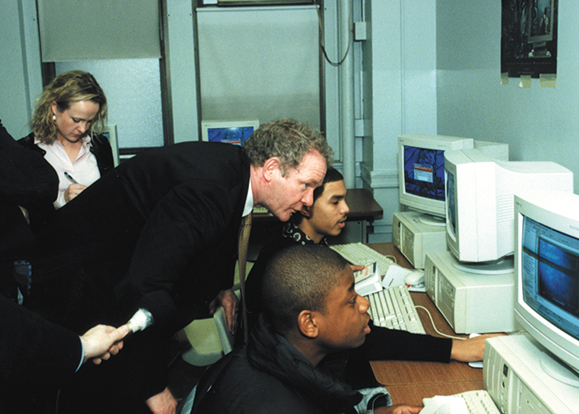

McGuinness visited several U.S. schools on the trip to get first-hand experience of how the U.S. Department of Education aims to improve academic standards in high poverty areas. One was the Edmund Rice High School in Harlem, named after the founder of the Christian Brothers order.

“First of all there was a big question about whether [the students] even knew who we were or where we came from,” said McGuinness, “but after 10 or 15 minutes you could clearly see the interest they had in us as individuals and on the political process and they were keenly interested in seeing Ireland.” There is talk of exchange visits between the school and schools in west Belfast.

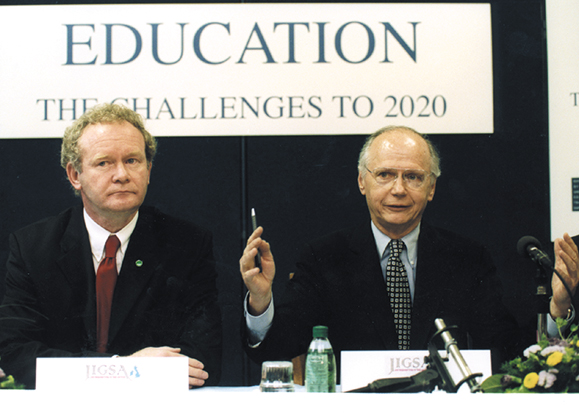

Cooperation between the two education departments has continued — a tangible “peace dividend” from the U.S. At the end of May, Riley visited Belfast to speak at an Irish American education conference with McGuinness, where the Sinn Féin leader commended the Clinton administration for its “central role in the search for a lasting peace on this island,” and noted that “Riley, both as part of the administration but also in his own right, has been to the forefront of those efforts.”

No individual has had a greater impact on the conduct of war or the achievement of peace in Northern Ireland over the last 30 years than McGuinness. And as Minister for Education, he probably has a greater influence on shaping the next generation than anyone else. “Be good students and work hard,” he tells the Bunscoil children. “Be good to your mammies and daddies and your teachers and if we all work hard together we are going to build a new Ireland.” ♦

Leave a Reply