William Kennedy on his unsung origins.

My grandfathers, George Kennedy and Peter McDonald, died before I was born. I came to know something of them through talks with my parents and other relatives, a few artifacts, death certificates and obituaries, and two photographs that defined them for me forever. Both photos are working-class portraits.

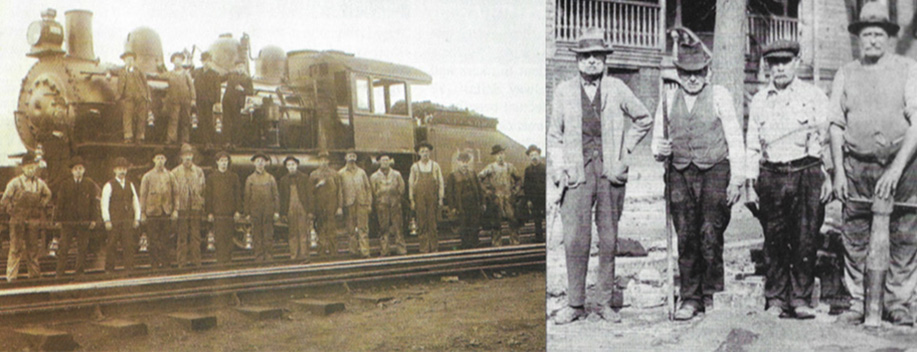

The portrait of George Kennedy is with three other men who are, I believe, from the Albany Water Department. They are pausing in their work on the granite blocks and water lines of an Albany street to pose with their tools – shovel, pickax, two-handed valve wrench, wheelbarrow – and George, second from left, holding a pry bar. He has a stubble of white whiskers in the photo, looks hunched and grizzled, and was probably near the end of his life. He is wearing a vest and a gold-plated chain for his pocket watch. I inherited the chain, perhaps also the watch, but I can’t be sure the watch was his. The chain is functional; the watch (whoever owned it) doesn’t work.

George had come to Albany in 1880 at age 20 from County Tipperary, worked as a laborer and risen to become yardmaster at the George H. Thacher & Co. foundry, which made railroad car wheels for the New York Central Railroad. He eventually brought over two of his brothers and two sisters, who all settled in Albany. He died in March 1923, of lobar pneumonia at age 63. His wife, Hannora Ryan (remembered as the sweetest of women, and who came from the next town over from George in Tipperary), had died in February 1896, also of lobar pneumonia, at age 29. My father, William, said she never recovered from the birth of his sister, Mary, some months earlier.

The Kennedys lived on Van Woert Street, a long, almost solidly Irish block at the edge of Albany’s Arbor Hill but considered part of North Albany, when my father was born in 1887. They later moved to a house next door to an ice house. In 1890, when my father was three, somebody torched the ice house; the Kennedy house went with it and the family lost everything. George moved from yet another home on Lawrence Street so my father wouldn’t have to cope with the horse and carriage traffic when he went to school, and finally, he moved back to Van Woert Street and stayed there.

In George Kennedy’s photo with the work gang his days of authority as yardmaster are behind him, as is his time as foreman at the Rathbone, Sard & Co. foundries (500 men employed, among them my father, who did piece work as a stove mounter, but quit when the wages per piece dropped from $1.35 to $.55). The iron and steel business went west toward the coalfields, and the coal stoves my father was mounting were made obsolete by the advent of gas. The times turned against George Kennedy, and in his late days he was again a simple laboring man.

I have a photo of a slightly younger George with his daughter, Mary, taken in 1917 when she was 22. George is at his social best: clean-shaven, hair tidily combed, wearing a dark suit, striped shirt with a white collar, dark tie, and the watch chain. He looks strong; he is square-jawed and handsome in this photo, but there is a grimness to his mouth and his eyes are sad. He lived the last 27 years of his life without his sweet wife, without a woman in the house, except when one of his sisters came by to clean the place. He could not raise baby Mary and also work, so he raised only my father, a wild, electric boy who was nine when his mother died. Hannora’s maiden sister raised Mary until she married.

The street photo of George came to me from Mary in the 1960s, and I was so moved by it that I thought of having it blown up to poster size as a way of advertising my origin, but that seemed as pretentious as trying to deny an origin. So I let it go unsung until now, when the chance to write about it thrust me into a search of the family archives and led to my first conversation with Mary Craig Hurley, 89, who lived on Van Woert Street, directly across from George.

Mary remembers George from 80 years gone. She sees him about 1912, when she is nine and he is 52, at a Van Woert Street house party – “all of Van Woert Street would be there” – and again at the annual clambake in Donovan’s backyard. George is always dancing and singing “The Stack of Barley,” an Irish reel.

“He did a marvelous dance,” Mary says, “and he had a good singing voice. I remember the words that he sang: ‘Oh my little stack of barley was the cause of all my misery…’ He was a wonderful man, a good-livin’ man.”

I am sure George Kennedy knew my mother’s father, Peter McDonald, who was born in Albany and lived on Colonie Street, a block away from Van Woert.

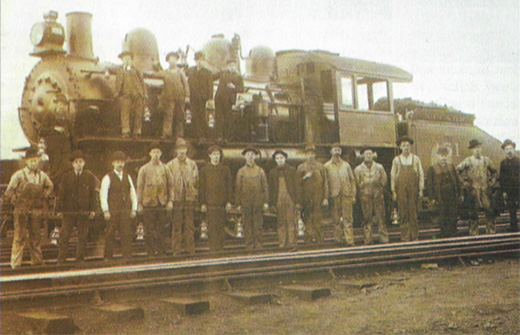

Peter’s photo, which hung in reverential space in our kitchen all my early life, is with a train and track crew, all standing with Engine 151 of the Central. (Everybody in the family played 151 when Clearing House, the numbers game, was vogue.) Peter is fifth from right, handsome, wearing a stylish scarf under his jacket and overalls, the only man in the photo so garbed. Swift Mead, an old-time boxer and saloonkeeper, said of Peter: “He was a dressed-up guy, always with a clean uniform. A hardworkin’ man.”

Peter began as a laborer and rose to become passenger locomotive engineer on Engine 151. He was given a medal for making a record-breaking run with the Twentieth Century, the Central’s greatest train, from Albany to Buffalo. The medal has been lost and the record of the run I haven’t yet found. But I believe it was a true record, for his children – my mother, Mary, my Uncle Peter, and my Aunt Katherine – would not have invented such braggadocio.

Peter fathered five children, two of whom did not survive infancy. He took sick in April 1916; the sickness lingered and he died in January 1918 of pleural pneumonia and myocarditis at age 43. His widow, Annie Carroll, the only grandparent I knew, lived with us and helped raise me. She died of complications after a stroke in 1951. I can’t remember her mentioning Peter, but I believe they had a very good marriage.

I inherited Peter’s scuffed black leather wallet in which he kept a record, during his illness, of his 107 visits to and by an Arbor Hill doctor, Marcus D. Cronin. In the last seven days of Peter’s life Dr. Cronin came to the house twice a day. The doctor bills came to $96, which my grandmother paid in two installments, in May and December 1918.

At the time of Peter’s death, both of his daughters were working in an office and supporting their mother and rambunctious young brother, Pete. I have very few memories from any of the three about their father. They were effusive in their love for him, but his death was four decades gone when I began to ask questions. I did inherit that wallet and his railroad pass for 1913, and military enrollment papers for World War I; also a postcard he sent to my mother in 1913 when she was at Camp Tekakwitha on Lake Luzerne in the Adirondacks. “Howdy toots,” he wrote her; “Don’t get drowned.” He said he was taking an engineer’s exam Monday and signed it P.A.P.

A clipping with his obituary was also in the wallet. “Mr. McDonald was stricken with an attack of pleural pneumonia about six months ago and it greatly weakened his heart. He had made a wonderful fight against great odds for the past few months, but his condition had been gradually growing worse up to yesterday when his heart finally gave out.” They don’t write obits like they used to.

The photographs of Peter and George are close to being terminal images: George, old in his 60s; Peter in his prime, at his career summit, a few years from a wasting early death. If you block off the chin stubble, George looks like my father. Peter looks like his son, Peter. My father inherited from George the love of song and dance (he was a prize waltzer), and Peter and his sisters inherited the wit that kept me laughing all my life. Neither inheritance shows up in the photos, but what is there are starting points for a continuity of family and meaning. These men – widower and widow-maker – are emblematic of what their children became and of what they passed on to us, the next generation: a veneration of ancestors, an appreciation of the working class, a bemusement with genetic gifts.

We really can’t know how guardedly, how limitedly, they lived, any more than they could have imagined life in the space age. Even my father didn’t believe it when men walked on the moon. “You damn fool,” he told me when we were watching them on television in 1969, “you can’t get to the moon.”

The streets and houses and people my grandfathers knew, the jobs they held – most are gone now, or obsolete. But George and Peter aren’t. There they are, standing for their portrait photos, offering up the gift and the challenge of creative memory. They look into the camera and say to us, “We were, now you are.” Anything after that is found gold. ♦

_______________

William Kennedy won a Pulitzer Prize for Ironweed, one of his six novels. Other novels in his “Albany cycle” include Legs and Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game.

Leave a Reply