Some thoughts on being Irish-American.

As a proud Irish-American, I begin with a simple assumption: there is no way to precisely define that elusive, complex human category called the Irish-American. The tools of sociology are as inadequate to the task as the forms of the Census Bureau, and the jeweler’s art of the lexicographer can’t come close to an answer. This should be no surprise.

It’s difficult enough to define the Irish or the Americans without being faced with a hyphenate, and that goddamned hyphen raises more questions than it answers. Is it wedged there as a sign of separation? Of dual loyalties? As an affirmation or a pejorative?

Millions of other Americans have been forced to struggle with the meaning of the hyphen. We speak easily of Mexican-Americans, and Chinese-Americans, and Korean-Americans; blacks now call themselves, with deserved pride, African Americans, but have managed to dodge the hyphen. And yet we don’t ever speak of English-Americans or Dutch-Americans or Canadian-Americans.

My friend the novelist Evan Hunter is the descendant of Italian immigrants, and he resists being called Italian-American. He felt no sense of ethnic betrayal when he changed his name from Sal Lombino to Evan Hunter; it was only a matter of being able to function in the literary marketplace of the late 1940s, when anti-Italian bigotry was still rampant.

For him, the Italian-Americans were the immigrants, those who arrived from Italy and became naturalized American citizens. Their children are just Americans. It’s a distinction I admire. But even Hunter told me that when he first visited Naples many years ago, he felt he had come home. I felt the same way when I first saw Ireland in 1962, swelling with an emotion as powerful as any I’ve ever felt. The writer John McNulty once wrote a piece for The New Yorker about his own first journey to Ireland and expressed that emotion in his title: “Back Where I Had Never Been.”

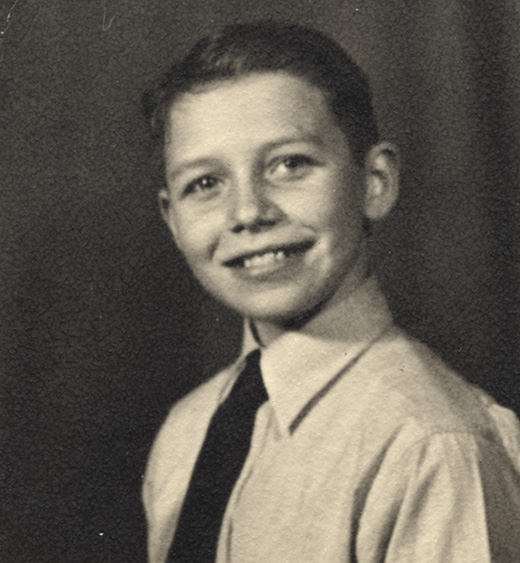

In the most obvious way, my feelings of Irishness were inevitable. My parents were Catholics from Belfast, who made their separate passages from the North in the 1920s and met some years later at one of the dances organized by immigrants in New York. I grew up in the years before television worked its leveling power on so many Americans, and so, from earliest consciousness, Ireland lived in my imagination. Ireland was in the songs sung by my father in bars, at weddings, at christenings and wakes.

Ireland was in the stories my mother told, and the Celtic myths she remembered. It was in the letters from Belfast during the blitz of World War II. When the war was over, Ireland was the destination of the CARE packages sent to unseen relatives. It was in the talk around kitchen tables filled with uncles and aunts and cousins, the Irish and their American children. My parents always called it the “Old Country.”

For me, as a child, it was a distant place where life resembled a kind of movie. In Belfast, in the neighborhoods of my own father and mother, British army boots still echoed on cobblestones. I.R.A. men in trench coats and cloth caps still moved on dark streets, and on any morning brave men might die in the foggy dew. The ruler was a dreadful man named Basil Brooke, who called himself a lord, and would never let Charlie Steele out of the prison ship in the harbor.

Sometimes my mother and father would join others on the Hudson River piers to protest the arrival of some person they called a bigot. Sometimes my father would sing a mournful rebel song. At the Minerva Theater, I saw Victor McLaglen in The Informer and realized that the informer was the worst form of human life. I saw Odd Man Out and thought that James Mason looked like my father. I knew even then that the movies were not life, but they did have power. My parents were Irish but were also American. They had rent to pay in Brooklyn and children to feed and clothe and educate, far from the Short Strand and the Falls Road. On Mondays they still went to work. Movies were for Saturday mornings.

In the years that followed, I read much about Ireland and then went to see it for myself. In the 1960s, I lived for two long periods in Dublin, and as a journalist covered the unfolding of the long and terrible war in the North. I was with my father in Belfast when John F. Kennedy was killed in Dallas, and saw Catholics and Protestants equally reduced to tears and wailing.

I learned much, and one of the things I absorbed was the attitude of the Irish, north and south, to the Irish-Americans. In those years, we weren’t considered Irish at all, an experience shared by the children of all other immigrant groups. If they went to Palermo or Warsaw, to Accra or Cork, they discovered that the hyphen didn’t exist. They were Americans.

Sometimes, Irish-Americans were greeted with affection by the Irish of Ireland. Sometimes they were objects of comedy; everybody had a story about some Returned Yank, gone for 40 years, who ran his hired car head-on into a bus while driving on the wrong side of the road.

Sometimes they were objects of malice, particularly in the bars of Dublin, where the prevailing begrudgery was the last defense of the colonialized mind. Sometimes they were subjected to primitive con games, with some pile of rubble in the countryside identified as the place from which some grandfather set forth for Boston or New York (these were frequently offered to visiting American politicians whose cynicism would accept anything). I’d like to think I was different; I’m certain I wasn’t.

But my journeys to Ireland did have a serious purpose that I’m sure was common to many other Irish-Americans. In part, I was attempting to learn more about Billy Hamill and his wife, Anne Devlin, to understand the forces that had shaped them and urged them to emigrate. Each carried a private template that was cut in Ireland, and lasted all their days. If I could understand them better, I might know more about myself.

I knew that their myths were not mine. My father carried Sinn Féin in his head and memories of long games of soccer with his friend Michael McLaverty, who became a fine Irish writer. He was full of rebel anthems and English music hall songs, the pubs of Leeson Street and the school where he had gone as far as the eighth grade.

My mother remembered the sound of horses at night and the beauty of the glens of Antrim she saw on one summer holiday and the silent movies in the theater where her mother was a ticket taker. Her father was dead by the time she was five. He was an engineer on the ships that traveled to Central America and Asia; she could hold his seaman’s papers in her hand, and recite the litany of places he had seen from the stamps in the book: Vera Cruz and Rangoon, Panama and Yokohama. All her life she had a curiosity about the world beyond the places where she lived. She remembered too the sounds of mobs swirling down darkened Belfast streets, prepared to kill in the name of Jesus.

My myths were different. They were primarily about Captain Marvel and Bomba the Jungle Boy and Jackie Robinson, a compost of comic books and classics from the library fertilized by radio serials, and images of the great American West seen in the darkness of Saturday morning movie houses.

The Irish part of my life was submerged in a vast American context; John Wayne, Al Capone, Billy the Kid, Gene Autry, the Durango Kid, Alan Ladd, Errol Flynn marched through my days and nights. My mother sometimes woke suddenly from an exhausted nap, startled and fearful, because in her dream the Murder Gang had smashed a door down in her house on Madrid Street.

The characters in my bad dreams took other forms: Nazi saboteurs led by the Red Skull into the war plant where my father worked; German bombers pounding Brooklyn; tidal waves at Coney Island; the gaunt skeletons of Buchenwald (after I saw the newsreels at the end of the war); ballplayers in pinstripes swaggering down from the Bronx to devastate the sacred grove of Ebbets Field. Those mythical differences were themselves the point. After all, one reason for my parents’ immigrating to America was to make certain that their children would not repeat their own bad dreams.

But because I was American, I was most powerfully shaped by influences that were not Irish. They were absorbed in school, on the streets, and later in the United States Navy. Even in our flat in Brooklyn, Franklin D. Roosevelt was more important than Éamon de Valera or Michael Collins.

During the war, and in the years immediately after the great Allied victories, we listened on the radio to Edward R. Murrow, Fulton Lewis, Jr. and William Shirer, and also to “The Make Believe Ballroom” and “Rambling With Gambling.” The voices and the ideas and the music were all American. So were the stories in the newspapers and the history taught at school. Americans wrote the stories; the world was seen through American eyes.

If I looked at a Norman Rockwell cover on the Saturday Evening Post I usually didn’t see my parish in Brooklyn, but I did see America. That’s what it was like, I thought. That’s what America was, and I was part of it. Ireland was important to my parents (although they naturally held some bitterness towards Belfast, and never once spoke about going back to stay) and therefore was of some interest to me. But as year after year passed, they became more and more American themselves.

In the late 1950s, I started to learn the craft of writing and that turned me more seriously to Ireland. I found my way to Jonathan Swift and Oscar Wilde, to Yeats and Joyce and O’Casey. I didn’t read them to affirm my Irishness, or to pretend that I understood every line they wrote, or to wrap myself in their unfurled banners. I never thought that because they were great writers, I could become one too. They weren’t even guides to conduct, models for the way a writer should live his life. I read them because no writer – and no educated human being – could not read them.

But they were not all that I read and were not the works that made me want to write. I was already living in a state of confused loyalties. The Irish part of me hated Elizabeth I and all her works, but I loved Elizabethan poetry, read it out loud during bouts of unrequited love and wished I could write with such power and beauty. The first show I ever saw in a theater was Hamlet, a gift on my 11th birthday; Maurice Evans was the star and though I did not fully understand what I was seeing I was swept away by the glorious language of Shakespeare. The English language.

I was trained to stay away from Protestant churches, but in the Brooklyn Public Library I saw clearly that the King James version of the Bible was one of the greatest of all human works, infinitely better written than the Douay version imposed in those years upon Catholics. I was not supposed to like or respect the English, particularly the rulers of Great Britain. But I loved Dickens. I was chilled and scared by Willkie Collins. I was enthralled by Robert Louis Stevenson.

All of those British masters (and many more) came with me as I set off on the road to becoming a writer. In one of his essays, Stevenson had urged writers to read like predators, and for a dozen years, I sat down to some extraordinary meals. They were, in fact, as varied as the restaurants in New York: French (Flaubert, Dumas, Maupassant, Balzac, Hugo, Stendhal and Camus); Italian (Dante, Boccaccio, Marcus Aurelius, Cesare Pavese, Alberto Moravia, Elio Vittorino, Ignazio Silone, Curzio Malaparte); Russian (Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekov, Turgenev); Brazilian (Machado de Assis); Spanish (Cervantes, Juan Ramón Jiménez, García Lorca, Camilo José Cela); Mexican (Carlos Fuentes, Juan Rulfo, Agustín Yañéz). I didn’t try to write like any of them, but all of them left some mark on me. In my imaginary library, a vast room full of the writers as well as their books, they shared the space with the Irish.

But all those writers were secondary to the Americans. In the 1950s, the greatest figure in American literature was Ernest Hemingway, and I was among the many thousands of young writers who succumbed to his spell. I discovered him in the library of a navy base in Pensacola, Florida, and quickly read everything he had published. Not once, or even twice, but over and over again. Hemingway created the notion of the writer as expatriate, rolling around the romantic places of the world from Paris to Pamplona. He had worked for newspapers; he knew James Joyce and lived like Lord Byron.

Hemingway led me to Pound and Eliot and Gertrude Stein, to Sherwood Anderson and Dos Passos, and back again to Mark Twain. It took me a while longer to “get” Faulkner, and I couldn’t read Henry James until I was in my forties.

But Hemingway was the one whose work urged me to try to write. At the same time, his dominance made me search for someone who was not like him (for in my youthful arrogance I did not want to be a mere Hemingway imitator). And then I began to read those other Americans who had come after him: Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, and Bernard Malamud.

Many of these writers were Jews, as were the critics and poets, and they began shaping me too. To begin with, they gave me, and many other Irish-Americans, the gift of irony. Reading them (and later, Joseph Heller, who did more to debunk the Hemingway myth than any critic) made us all more conscious of the difference in America between what was promised and what was delivered. They too were the children of immigrants. They too were the children of cities.

In the 1950s, no writer could avoid the triumph of Jewish ideas, art, and attitudes, but Irish-Americans were particularly susceptible. Too many Irish-Americans had retreated from their origins into a tight-lipped conservatism, nodding pious assent to such sour zealots as Cardinal Spellman, while condemning such splendid Irish-Americans as Paul O’Dwyer.

The Jews, in contrast, were loose and liberal and irreverent; that is to say, confident in their American identity and able to write Yiddish shtick too. They were much more like the Irish than they were like John Foster Dulles. Their freedom, wit, and intelligence created a sea change in American culture. It could be seen in many places, from Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad comics and Jules Feiffer’s brilliant cartoons in the Village Voice to the poetry of Delmore Schwartz. The Jewish sensibility drove most American comedy, from Jack Benny to Sid Caesar, Mel Brooks to Lenny Bruce. It could be felt in the movies and in popular music and even on the sports pages. And so, to be Irish-American in the 1950s and 1960s was also to be in part Jewish.

At the time, the only Irish-American writers I had read were F. Scott Fitzgerald, John O’Hara, and James T. Farrell. I thought The Great Gatsby was a masterpiece (and still do) but it had nothing to do with my own experience as an Irish-American. O’Hara was a fine writer, with the greatest ear for the nuances of American speech of anybody before or since; but his Irishness was often defensive and surly and he had a reverence for the institutions of WASP Americans (particularly their schools and clubs and inner sanctums) that was unhealthy for any writer. Farrell was Irish-American, and though I never tried to emulate his work, he did (along with Paddy Chayefsky) help me to understand that the life I knew in Brooklyn might be the proper subject of serious writing. It was not necessary to write about war or bullfighting or smuggling in Key West. The world could reveal itself right up the block.

I realize that being an Irish-American writer is not the same as being an Irish-American businessman or cop or designer or school-teacher. But I do think all Irish-Americans born during or after the Depression were subjected to the same American influences. Not all studied painting, as I did, or went off to Mexico on the G.I. Bill, as I would do at 21. But in addition to the influences of the Jews, all of us were shaped by the music made by African Americans. If we lived in New York, Chicago, the Southwest, or California, that influence includes the branch of African-rooted expression we call (too broadly) Latin music. From early jazz to rock and roll, there was a powerful black component in American culture. And it entered all of us.

To be sure, the attitude of too many blue-collar Irish-Americans towards blacks and Latinos was ugly. Too many sneered at the “sp**s and n*****s,” occasionally acted brutally towards them, or fled to the suburbs at the sight of black faces in the neighborhoods. In my experience, this was more true of third- or fourth-generation Irish-Americans than of the children of immigrants. Those who had served in World War II were part of a segregated army. The black migration to the North was just beginning and so they had no contact with blacks in schools.

Worse, these Irish-Americans had no memory of the anti-Irish bigotry endured by earlier generations of the Irish in America. They knew very little about the prevalence of Irish crime in the 19th century, and how the prisons were packed with the Irish, and how the established New Yorkers reacted with anger, fear, and racist prejudice to the arrival of so many Irish men and women. If they had known any of that, they’d have realized that what they were saying about blacks and Latinos was almost word for word what the WASPs said once about the Irish.

Not much immigrant history was taught in public or parochial schools. But these Irish-Americans made no effort to learn their own history, to read the narratives of African-Irish alliances that led to violent rebellions in South Carolina, Philadelphia, and New York in the 18th century.

Nor did they know of the shameful behavior of some Irishmen during the Draft Riots of 1863, when mobs of louts set fire to the Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue, or of the heroic actions of Irishmen who rescued those children from being burned alive.

For too long a time, in short, there was a mixture of willed ignorance and amnesia among too many (but certainly not all) Irish-Americans, a condition worthy of close analysis by scholars. Some of it surely came from too long an immersion in the culture of blame. Your unhappiness or failure or continued marginalization must be somebody’s fault, but never your own.

It was the fault of the British. It was the fault of the landlords. It was the fault of the Protestants (or the Catholics, if you were Protestant). It was the fault of Roosevelt and the New Deal and the liberals. This was often combined with the deep, abiding conservatism that attaches itself to country people of all nations. That conservatism was understandable; a farmer must know that the sun will rise at a certain time and the rains fall in a certain season. He does not want change. Certainly no changes in weather or climate, and preferably no changes in society. For people who live off the fruits of the earth, change of any kind is a danger; it can bring tumult and disruption and hunger. For city people, change is the only certainty.

So in my experience as an Irish-American, there were few bigots descended from immigrants who came from Dublin or Belfast, Cork or Derry. Their people were from cities and therefore accepted – even embraced – the notion that there were people who were Not Like Us.

Two immense forces began to shift the psyches of Irish-Americans of my generation. One was the arrival in 1947 of Jack Roosevelt Robinson to play at Ebbets Field. He didn’t simply integrate baseball; he integrated the stands. And the bigoted reactions of some ballplayers in Robinson’s first season forced the children of all immigrants to ask the first moral questions of their lives.

The other great shift was black music. From the 1940s on, black musicians and black music entered the mainstream in the same way that black athletes did: through sheer force of talent. Nat King Cole and Billy Eckstine had delirious white fans. At night, I would listen to the disc jockey Symphony Sid and began to absorb the high art of bebop: Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Max Roach.

I listened to Basic and Ellington, to the extraordinary saxophone of Ben Webster, to the amazements of Roy Eldridge on trumpet, to the cool brilliance of Clifford Brown. Billie Holiday eased into my mind and stayed forever. I lived into the nights with Louis Armstrong and Champion Jack Dupree and went drinking with Bessie Smith. I was Irish-American, but all of that was mine too.

All of those artists shared a quality that Irish music at the time did not possess: authenticity. After listening to Lady Day, who could yearn for “Mother Machree”? After dancing to Basie’s “One O’Clock Jump” who the hell wanted to listen to “MacNamara’s Band”? There were too many Irish songs about rural Ireland, about houses with thatched roofs and weepy grandmothers, too much syrup and sap, too many comic turns in the shameful tradition of the Stage Irishman. I didn’t want to be like Dennis Day, who sang “Clancy Lowered the Boom” for Jack Benny, I wanted to be like Duke Ellington.

The truth was that until the arrival of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem in the early 1960s, most “Irish” music was Tin Pan Alley slush (the story of that music is marvelously told in William H.A. Williams’ study, ‘Twas Only an Irishman’s Dream; Indiana U. Press. 1996). Written for the immigrant market, and used, as was the Stage Irishman, to ease WASP fears, this music was the equivalent of the green beer and shamrocks and kiss-me-I’m-Irish nonsense of St. Patrick’s Day, and its most sustained American voice was that of Bing Crosby.

The music could have its sentimental appeal, and Crosby was a gifted man. But in comparison with black American music, when measured against the blues, or the country music of Hank Williams, Webb Pierce, and other Southerners who worked out their own variations on an Irish musical base, it felt like a lie. Mainly because it was a lie. No wonder that my Irish-American friends and I pledged our fealty to Frank Sinatra, who was making an authentic urban music infused with stoicism. No wonder we still make a break for the door whenever anyone breaks into “Danny Boy.”

Such reactions were not a rejection of Ireland. They were a rejection of falsity and self-delusion. And they were a rejection of the narrow, conservative, tight-lipped definition of Irishness that had become quasi-dogmatic in the 1950s. In the 1960s, the dam broke. There was a growing insistence by some young Irish-Americans that to be Irish was not always to be Catholic. The civil rights movement in the United States found an echo in Northern Ireland, with young university-educated Catholics singing “We Shall Overcome” on the roads of the North.

The Calvinistic pieties of J.C. McQuaid’s Irish church, with its book bannings and mutilations of films, its sustained assault on every form of modernity, looked more and more absurd, and helped get people killed in the North. The hip young Irish were also listening to Lady Day and Charlie Parker, to Sinatra and the blues. In spite of censorship, they were finding Joyce and all the other banned writers, and being shaped too by the high art of Flann O’Brien.

And from the North as the dam burst, here came Seamus Heaney and Derek Mahon. Here were Seamus Deane and Paul Muldoon, Michael Longley and Ciaran Carson, all building on an Irish foundation, on Yeats and Swift, on Patrick Kavanagh and Austin Clarke, but informed by the poetry of the world. Young readers looked more carefully at Louis MacNiece, liberating him from Auden’s shadow; they discovered the brilliant, heartbreaking Protestant Irish visions of John Hewitt, which had been there all along. And on jukeboxes in Belfast, you could hear Aretha Franklin, demanding respect, along with the sly baritone resistance of the Dubliners.

The North, the goddamned North: men and women and children dying, Catholics dying, Protestants dying, old women dying, soldiers from Liverpool or Leeds dying. Bombs shattering buildings. Armalites fired in the night. Ambushes on the roads near Strabane. Who in that time and that place could sing about the Rose of Tralee? Or urge Paddy Reilly to come back to Ballyjamesduff? The music of the North was rock and roll.

All the blood, all the sacrifice and heartbreak, strongly affected the Irish in what was increasingly referred to as the Irish Diaspora. Irish-Americans were forced to think about the word that preceded the hyphen. Some honorable Americans simply gave it up; the events of the North were an embarrassment, a murderous 17th-century quarrel that was beyond all rational solution. Others were forced to think, and some, to act. They wrote for newspapers. They wrote to congressmen and presidents. They insisted, like the wife of Arthur Miller’s Willy Loman, that attention must be paid. And yes, some raised money for guns.

But the shift of Irish consciousness was irreversible. Ireland was no longer some isolated misty offshore island; it was part of Europe. In the past six or seven years, the great advances in the Irish Republic have impressed the world and can’t be dismissed with glib jokes about the Celtic Tiger.

Irish-Americans have been a part of those changes, with business investments, with political support for the peace process that was so galvanized by Bill Clinton, and with a growing sense of discovery of Irishness that is deeper and more authentic than the banalities of the past.

As the Catholic Church began losing its secular power in the Republic (for complicated reasons), there was a greater awareness among hyphenated and unhyphenated Irishmen of the pre-Christian past. This was enriched by Irish archaeological discoveries and scholarship, and the publication of splendidly illustrated books. Even the nature of tourism changed; the nonsense about Irish pubs and Joyce’s tower remained in the advertising, but many Irish-Americans also found their way to Newgrange. Nobody, after all, went to Ireland for a tan.

But the changes were swifter and wider than anyone could have anticipated. Irish theater rose from its status as a kind of musty museum of the theatrical past. Superb Irish films could be seen all over the world and received all the important awards. Irish music changed, drawing deeply on the Celtic past. Riverdance was only one of a number of cross-fertilizing events that forced all Irish-Americans to think in fresh ways about what is so carelessly described as their heritage. The days of my youth, when we thought the Marine Corps Hymn was an Irish tune, are long gone, and bad cess to them.

The modern world also changed the nature of emigration. Membership in the European Union allowed the young Irish, longing for a world beyond the parish, to study or work in Italy or France or other countries in Europe; they did not have to choose between Boston or New York, or as Evelyn Waugh once said, “between hell and the United States.”

Even those who came to the United States were different from their predecessors; they were more urban than rural, better educated than any previous generation, more at ease in cities. Because of the airplane, it has been a long, long time since any Irish family gathered for an American wake. Now there are more Irish returning to Ireland than staying in America. They go home with computers instead of pensions from the telephone company or the police department; and if they stay they read The Irish Times on the Internet. All changed, changed utterly, man.

And because of all these changes, because of the prolonged effect of the killing in the North, and Ireland’s own swift embrace of the modern temper, nobody can define the Irish-American. I think of myself as typical of Irish-Americans of a certain generation, shaped by World War II, by poverty, by family, by Buchenwald and Hiroshima, by the influences of American Jews and American blacks. I was also deeply affected by living in Mexico, where I was the marginalized man, I was the minority, I was the newcomer. That is, I’m not one neatly categorized person, and neither is any Irish-American. We are triumphantly plural.

But mysteries persist. We all know that there is no genetic definition of any ethnic group; to say, for example, that the Irish have a genetic weakness for alcohol is scientific and intellectual rubbish.

But I do believe we are shaped by history – shared history and the histories of our individual families and clans. And there is, in fact, some mysterious current flowing in many ethnic groups; a few psychological theorists of varying levels of respectability call this secret river “genetic memory.” This also might be nonsense, a function of the power of the human imagination rather than something encoded in DNA. But one thing can’t be denied: it is present in many Irish-Americans.

I have felt that secret current while walking on Broadway or wandering through Chapultepec Park in Mexico City. I hear something else first: a fragment of song, a certain accent, a woman’s murmurous voice, the roll of a drum. Then the secret music flows, transcending time and geography, reaching me from all the lost centuries of Ulster. It touches me in some secret place, penetrating a part of me that no other sound or art or music can even locate. Sometimes it’s provoked by the sound of rain on granite. Or an abrupt flight of city birds. Or a bluish cloud scudding across a sky at dusk. And for that long moment, I am who I am: my parents’ son, out of Belfast and the wrong side of the lough.

My mind tells me I’m an American. But I also feel that I’m a tiny fragment of a much longer story, perhaps a mere noun, but carrying with me all that pain and passion, all that sacrifice that did not make a stone of the heart. I wander with Leopold Bloom. I fall bleeding with Cuchulainn. I am brandishing a pike on a blasted hill and waving my defiance. I am dancing, wild and naked, under a scarlet moon.

And, yes: I am of Ireland. And I am not alone. ♦

_______________

At the time of writing Pete Hamill was on the staff of The New Yorker. He was finishing a long novel about New York called Forever, and a television documentary about Leonardo Da Vinci. He died on August 5, 2020. He was 85.

**What I have come to know about being Irish I learned from Peter Quinn.

Emigrants

for Peter Quinn

One hundred thirty now,

the lingering years gone

since my Moran fled

the pathetic coast

of Mayo, longing toward

some imagined redress.

Today, faces so like

my own, familiar as

whistle and harp notes,

ask, “Have you been?”

and “When will you get

home again?”

Sadly, I cannot say except,

I know I will be there soon.

And when I am, at last, I will

bend to kiss that ground

softly like the forehead

of an aging mother,

Shake hands with a thousand

cousins, listen for the poems

trapped in hill and bog.

I might cast a slackline

for a silver rainbow, smell

the grass at the chapel wall.

Standing before the cliffs,

I’ll raise a warm pint of ebony

and foam, and face myself into

the bite of the briny breeze.

To the memory of all my dead,

I’ll call out to the back of the sky,

Allowing my blue eyes to moisten

with the pains of the leaving.

I’ll recite in tender meter every regret,

and wonder from the bare heights

of the lonesome Connacht shores,

at how it was the wind had

carried us so very far away.

Daniel Thomas Moran

Wow! Lovely complicated tribute to being Irish American!