Martin Sheen, the star of The West Wing, is a complicated, ebullient tangle of philosophy, Catholicism, politics, altruism, and homespun wisdom.

It’s a disconcerting sight: The leader of the free world is, uh, combing his eyelashes with a small mascara applicator… Okay, so it’s the make-believe leader of the free world. And it’s not such a far-fetched notion that Martin Sheen would eschew being fawned over at a photo shoot. After all, the Dayton, Ohio-born actor has been arrested close to 60 times for acts of civil disobedience. He’s spent days handcuffed to chain-link fences outside nuclear reactors; he’s spent nights in jail. He’s fed the hungry in soup kitchens. An avowed left-leaner and fervent Catholic – he makes no bones about his faith, and often wears it on his sleeve – Martin Sheen isn’t afraid to roll up those sleeves and work for causes he believes in.

So the makeup artist sits on her hands as Martin Sheen tends to himself. Still, it’s disconcerting to see the faux-president – Sheen plays President Josiah Bartlet on NBC’s acclaimed drama The West Wing, for you folks who live under rocks – readying himself for his close-up. He’s breezed into this spacious Soho photo studio sans publicists and minders for this interview, claiming to have taken the subway – “I used to live right around here in the sixties, I still know my way around,” he says – and greets all around with a warm handshake. “Hi, I’m Martin,” he says to anyone nearby, delighting in smashing the all-too-common actor’s wall of ego.

Actually, he’s Ramon. Ramon Estevez, the seventh of 10 siblings, nine boys and a girl. Born on August 3, 1940 in Dayton to a Spanish-born father and Irish-born mother (“she taught me all the Irish songs”), Estevez took the stage name Martin Sheen upon moving to New York in the early 1960s to pursue acting. (“Martin” came from the last name of a casting director friend; “Sheen” from the ubiquitous TV bishop.) Unlike countless other Hollywood types, Sheen has been married to his wife, Janet, for nearly 40 years. And he is patriarch of an acting family — daughter Renée Estevez and sons Emilio and Ramon Estevez and Charlie Sheen have achieved varying degrees of fame, and infamy.

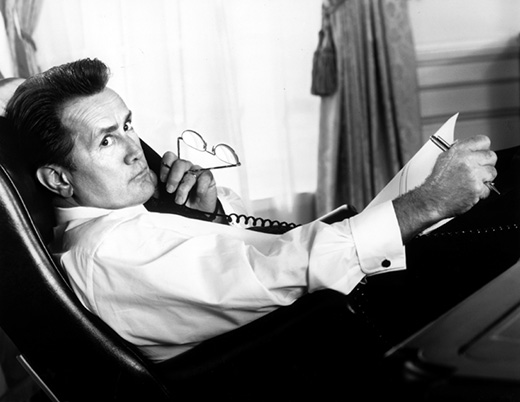

Now 60, Sheen is thicker than the sinewy youth who made his big-screen debut as a punk who terrorizes subway riders in Larry Peerce’s The Incident, in 1967. But the grip is firm, the forearms taut, the blue eyes clear and intense. And the sandy hair, now flecked with gray but still standing at attention, still evokes James Dean.

In fact, it was a James Dean-styled character that put Martin Sheen on the cinematic map. Sheen played Kit Carruthers, a brooding drifter who takes Sissy Spacek’s Holly Sargis on a killing spree through the American Midwest in Terrence Malick’s 1973 film Badlands. Sheen’s performance drew heavily from Dean, and he was cited by many critics as an actor on the rise.

He’s had other notable roles as well: Sheen played a principled plane mechanic and union leader, opposite his son Charlie Sheen, in Oliver Stone’s 1987 greed treatise Wall Street. He’s appeared in solid films such as Gandhi, Catch-22, and That Championship Season. His directorial debut about teenage mothers, Babies Having Babies, won an Emmy in 1986.

But it was his portrayal of Captain Benjamin Willard in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now that was Martin Sheen’s breakout. The film’s opening sequence, in which Willard whips himself into an alcohol-fueled dervish-trance to prepare himself for his next murderous mission, was one of Sheen’s most memorable moments on celluloid. According to the actor, he was drawing from experience. “I had the wolf by the throat – or rather the wolf had me,” says Sheen of his alcoholism.

The filming of Apocalypse Now took a heavy toll on Sheen: the shoot in the sweltering forests of the Philippines, which was scheduled for four months, actually took 18, and Sheen suffered a heart attack during filming. “It was one of the most important events of my life – I was redeemed by it,” says Sheen of his Apocalypse Now epiphany. He gave up drinking and has been sober since. “Mind you, if you had told me going in that this was going to happen to me, I’d have said, ‘No thanks, I’m out of here,'” he says with a knowing, hearty laugh.

Martin Sheen has good reason to laugh these days. His TV series, The West Wing, is a critical and ratings success, and has given Sheen a career boost as he enters his fifth decade of acting. Sheen plays President Josiah “Jed” Bartlet, a blunt, commonsense pragmatist who wrestles with his presidential decisions and his faith.

“They’ve allowed me my Catholicism, which places the issues we raise on the show in a moral frame of reference,” says Sheen. “To see the most powerful man in the world get down on the floor of the Oval Office and ask forgiveness for his sins – finally I got to do something personal.”

Why does Sheen think The West Wing has resonated so strongly with the American public? “I think we are causing public debate on some very undebated issues,” he contends. “We’re talking about gun violence, about justice, about racism, about the environment, about these issues that touch us. I think that’s what people are responding to.

“Try to describe our show to someone who’s never seen it before,” Sheen continues. “We’ve got a show with eight or ten people, who work indoors with no windows, mostly talking about politics. There are no special effects, no car chases, no computer graphics. It’s just about relationships, people talking.

“That person might say the show is a soap opera. But it’s not, it’s something much more than that,” he says.

Sheen decries the state of dramatic television these days, and is thrilled to be working on a program with such a high caliber of writing. “I think there’s still a lot of good stuff on TV,” he says. “But it’s not in the area of drama, it’s in the area of news coverage, documentaries, and sports. Television doesn’t get better than with sports. But in the area of drama, it’s below par because movies are so powerful. TV has become a lot of pap. The biggest shows are half hour sitcoms with loud exchanges, canned humor, sex jokes. There’s very little substance.”

Sheen jumped at the chance to work again with Aaron Sorkin, who is the creator, executive producer, and a writer for The West Wing. The two had worked together on the 1995 feature film The American President, and Sheen has nothing but praise for the show’s creator. “We have a saying around the set – ‘Aaron is the reason for our season,'” Sheen says. “The show has gotten better and better, and closer and closer to the edge.”

Sheen does harbor some doubts about his character, however. “President Bartlet is often a vengeful president when it comes to the Arab world, which troubles me, Martin, greatly,” he says. “I’m always fighting for diplomacy rather than military intervention. This is a constant debate we have on the show. But we do have to satisfy the other side sometimes, give a voice to the right.

“But me, I’m so radical I tend to go overboard. I’d sail the ship of state downstream, you know what I’m saying?”

The cast of The West Wing was given uncommon access to the White House in May for filming a couple of late-season episodes. “The people around [Clinton] are extremely bright and down to earth, they couldn’t have been more hospitable,” Sheen says. “I felt we were taking up a lot of their time, yet they were so generous with us. I loved the interchange.” Sheen even had a brief meeting with President Clinton; the television president meeting the real one. “I got very tongue-tied with him,” Sheen says. “But I told him that I loved him and the job he was doing.”

And did Clinton have any comment about the job Sheen was doing in The West Wing? “We’ve tried to make the show a reflection of public service, not politics. And we’ve tried to put a name, a face, an energy onto this administration in a deeply personal way. The president was grateful for that.”

Martin Sheen has made cinematic forays into the White House into somewhat of a personal cottage industry. In addition to his Bartlet character, Sheen played chief of staff A.J. McInerney in the 1995 feature film The American President, John F. Kennedy in the 1983 miniseries Kennedy, and Bobby Kennedy in the 1974 miniseries The Missiles of October.

Sheen has few regrets, but portraying Jack Kennedy is one of them. “It shouldn’t have been done, quite frankly. I was ill prepared, the company was ill prepared. He’s too big an icon to portray. It was hopeless,” he says.

Sheen turns downright evangelical in talking about the late president. “The image of that brilliant, handsome man, that young father – Kennedy sparked an energy, enthusiasm, idealism. He changed the world! He’d express an idea and it became policy. He said, ‘We’re going to the moon,’ and we got there in less than ten years! He willed it.

“The main ingredient of his administration was confidence,” continues Sheen. “He was like a cocky, streetwise Irishman. He cocked his hat. He knew he pissed some people off. He had a knowledge of the media, and he played it like a piper. He knew exactly how to get them to dance to his tune. He was charming and brilliant, and people were in love with him and he knew it.”

Playing the Kennedy brothers had a great effect on Sheen, and he still mourns their loss. “That family is indelibly etched in my heart,” he says. “JFK’s death was bad enough, then Reverend King, which was another massive wound, then Bobby. This country is still crippled by their deaths. Crippled! We lost Bobby, and got Richard Nixon. Gimme a break. We never got over Nixon.”

And what is Martin Sheen’s take on the current presidential campaign? “I admire John McCain,” Sheen says. “I wish he hadn’t thrown in for George Bush. He has no way of finding out how much the American people support him by closing up shop. Go out and slug it out with that bastard.” Sheen can’t mask his contempt for the conservative Texas governor. “Fight that money, fight that arrogance, that upper-crust privileged lad from Texas,” Sheen exclaims. “He [McCain] would scare the shit out of George W.”

Though Sheen admires McCain, he’s troubled by the Arizona senator’s reference to his North Vietnamese captors as “gooks,” and thinks McCain’s recent much-publicized return to the Hanoi Hilton was grandstanding. “He ought to realize that they made a man out of him,” Sheen asserts. “They made him as strong as he is. He still can’t let it go.”

Martin Sheen is a man who acknowledges – and celebrates – his Irish roots. He keeps a home in County Tipperary and holds an Irish passport (in addition to his American one). “I love Ireland,” Sheen says. “I think I love it too much.

“Ireland is one of the few countries in Europe that has never invaded anyone, never beat anyone up – except when they fought the British – but Ireland has never conquered anyone,” Sheen says. “What Irish flag was ever planted on foreign soil and claimed for itself? None.

“They sent missionaries, they sent writers, they sent artists, they sent nuns, they sent teachers into the world. Which is far more powerful,” he says. “I love to go to other parts of the world and meet Irish people. You go to some of the worst situations in the third world and you’ll find Irish nuns, Irish doctors, you meet Irish priests, Irish laypeople serving. You say to them ‘What the hell are you doing here?’ and they’ll say, ‘Sure, why not?’ It makes perfect sense.”

His late mother, the former Mary Ann Phelan, fostered a sense of Irishness in the Estevez home. “She was so feisty, so cocky. I learned all the Irish songs from her,” says Sheen, fondly.

“We were all kind of suspicious why she left Ireland,” continues Sheen. “She had an education, she spoke Gaelic, she went to Dublin to study. They came from a poor village but they had a pub. My brother Manuel was born above the family pub, Phelan’s, on Mill Street in Borrisokane.”

According to Sheen, there’s a certain brand of Irish logic that suits him just fine. “They don’t make a bit of sense, which is fine with me because I don’t make sense either,” he says. “What’s it called when somebody says one thing one day and the complete opposite thing the next day and they’re both right? Irony? That’s Ireland.”

Sheen recalls an instance of that Irish logic while filming a television version of Hugh Leonard’s Da in Dalkey a decade ago. “We were shooting this scene, and up on the hill in the background was this drunk and disorderly fellow, he was destroying the sound.

“[Director] Matt [Clark] sends one of the assistant directors up the hill to get this guy out of the way. When the kid gets up there, the drunk guy yells at him, and we think there’s going to be a fight. The kid comes back down the hill, saying, ‘I can’t move him.’

“So along comes a Garda, and he goes up the hill to try to get the guy to move. They talk for a while, but the officer comes back down the hill as well. So Matt says to the Garda, ‘Why didn’t you throw him out of there?’ The officer says, ‘Ah no, sure he was here first.’

“And that’s Ireland,” Sheen says. “Never mind that there was a movie going on. That drunken lad was an Irish citizen and his rights weren’t going to be taken away to please us, movie or not. Man, it made me love the country even more!”

Sheen then went up the hill, and was able to coax the man down by showing him around the movie set. Turns out the fellow was a fisherman, and he later provided the film a valuable service. “He was the one responsible for getting all the fishermen to help us shoot the scene at night, with the storm at sea and the poles in the water and so forth. This guy was responsible for all of that. He became our friend,” Sheen says.

After the movie wrapped, director Clark ribbed Sheen about the drunken fisherman incident. “Matt said as soon as you went up there, the man realized he was talking to the President of the United States, John Kennedy. That’s who made him come down – not you, Martin,” Sheen recounts, with a hearty laugh.

Humorous anecdotes aside, Sheen is well acquainted with Northern Ireland politics, and is not afraid to opine on the topic. “If David Trimble had half – a third – of the courage Martin McGuinness and Gerry Adams have, we wouldn’t be where we are today,” he says. “I’m terribly proud of Clinton’s foreign policy. I could nitpick, I suppose. But we would not have a Good Friday Accord if not for the president. He took some real chances.”

While on the subject of Northern Ireland, Martin Sheen recites a poem titled “Heaven of Freedom” by the Indian philosopher Tagore, which he learned while filming Gandhi. (He’s changed the word “mind” in the first line to “heart,” claiming it translates better that way.)

“I recited this to Gerry Adams, and he had the words painted on the walls of a community center over there,” he says. It reads:

Where the heart is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by Thee to ever-widening thought and action;

Into that heaven of freedom, my father, let my country awake.

The photographer is ready. One gets the sense that Martin Sheen, a complicated, ebullient tangle of philosophy, Catholicism, politics, altruism, and homespun wisdom, is truly gratified by the impact The West Wing has had on the American viewing public. “Our agenda is to debate tough issues, and people are getting a foothold on the debate,” he says. “There’s a saying – ‘You can’t unring a bell.’ That’s what we’re doing – we’re ringing a bell.” ♦

_______________

Tom Dunphy is a regular contributor to Irish America. He has had his work published in the Irish Voice, the Bergen Record, and LiveMusic magazine.

Leave a Reply