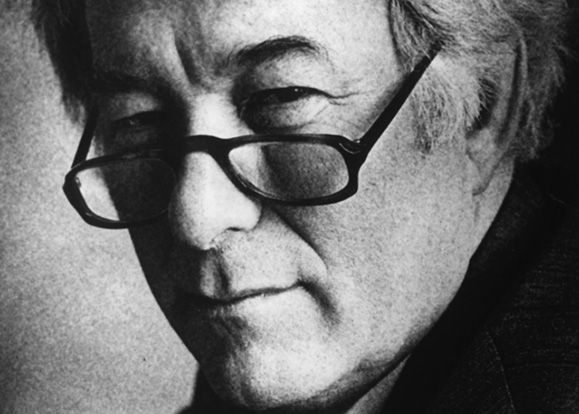

A native of Northern Ireland, Seamus Heaney won the 1996 Nobel Prize in Literature. The following excerpts are taken from interviews conducted with him in 1986 and shortly after he won the Nobel in 1996.

Poetry summons you. That’s been my own experience. The real difficulty about being a poet is not in the writing. It’s surviving the silence, surviving lack of inspiration, and the feelings of fraudulence that are upon you when you go for, say, six months and you haven’t written anything. If you start to think about it you could panic and never write another line. Most poets live in a state of panic. And that’s what’s really so difficult and sore. And it’s in store for all poets, that time when poetry leaves, when you know you’re not writing as well as you used to.

At a certain stage of being established a writer can publish anything, alas! and on the whole it will be greeted all right. If by the age of 50 you’re in the anthologies and you’re still producing, well, you can keep dawdling it out forever and unless you yourself know, nobody is going to help you very much. But you know when you’ve done something good, and you know when you’ve done something bad, and it’s surviving that knowledge that is the real test. – May 1986, Kate O’Callaghan

There seems to be something in the Irish that makes them partial to poetry.

There’s a tradition, a value system, which is given a historical myth or truth that predisposes us as a community and as individuals to trust in poetry. If a poet publishes a poem in a newspaper in Ireland, the judges will read it, the Taoiseach will read it, the Protestant bishop will read it, and the name of the poet will be a possession. I think it’s a matter of some indifference whether they are equipped in any special way to read or judge poetry. We are talking about the actual role of the poet in society, and in Ireland there is no doubt that the role is alive and contrasts vividly with what will happen if a poet publishes a poem in the Times of London, or in The New York Times. So, fearful as I am of talking up romantic notions about Ireland, I think you have to concede that there is public, psychic, and artistic reality in this, which is a genuine positive cultural possession of the country.

Do you still see yourself as a citizen of the North?

The image I have is of the ripple going out, which is an image you can find in Joyce’s work: for him it was Sallins, Kildare, Ireland, British Isles, Europe, the universe – for me it was Derry, St. Columb’s, Queens, Berkeley, Wicklow, Harvard, Oxford, it’s the same soft of ripple. There’s a part of you that’ s still an extension of the original self moving at the circumference of your adult cognition and realization.

Do you think living in Ireland is essential to your poetry?

I don’t think it’s essential but – I don’t know the answer. The last 25 years have been so stressful and crucial it would seem to me that I couldn’t have knit myself into something workable without staying in Ireland. – May / June 1996, Patricia Harty ♦

Leave a Reply