The English Catholic martyr, St. Edmund Campion, lived in Dublin for a while in 1569 and here is what he wrote about the Irish: “The people are thus inclined: religious, franke, amorous, irefull, sufferable of paines infinite, very glorious, many sorcerers, excellent horsemen, delighted with warres, great almes-givers, passing in hospitalitie: the lewder sort both clarkes and laymen are sensuall and loose to leachery above measure. The same being vertuousle bred up or reformed are such mirrors of holiness and austeritie that other nations retaine but a shew or shadow of devotion in comparison with them.”

If you’re Irish, you’re searching for yourself in Campion’s wide-ranging assessment. Are you religious one minute, “sensuall and loose to leachery” the next? Amorous, but still a mirror of holiness? Much depends on where and when you grew up. If, like me, you were raised in mid-century Ireland, you had to think twice before engaging in sensuality and lechery and if you did there was nothing for it but confession on Saturday.

My Ireland was known the world over as “poor and priest-ridden.” The Irish were marrying so infrequently and emigrating at such a rate that an alarmed American priest wrote a book entitled The Vanishing Irish. We were poor. We were priest-ridden. And de Valera-ridden.

These were the ingredients of our lives in the lanes of Limerick and, I’m sure, in lanes in every town and city in Ireland. But especially in Limerick because this was the one major city in Ireland without a university, a community of independent thinkers and scholars. Dublin, Cork, Galway, Belfast – all enjoyed social and intellectual benefits of higher education, but not Limerick. There was an intellectual (and spiritual) vacuum – and the Church filled it.

There was no political vacuum: de Valera had already filled that with his various obsessions, his dreams of a Gaelic-speaking people digging joyously in the fields by day, dancing in the dusk at the crossroads, Irish dancing only, leaping lads ready to die for the creed and country, dimpled maidens so chaste they put the lie to Campion’s sensuality and “leachery.”

Why go on about this? It’s old stuff and haven’t Irish writers, from Joyce to McGahern, exhausted this vein? No, you can’t exhaust it because that Ireland, with its tricolor, its crucifix, its various blood sacrifices, has affected generations of Irish even unto seven times the seventh generation.

And the irony is that even Irish Americans may have been affected by the psychological climate of the mid-century Ireland. That’s easy to spot: there’s the accent. When they say, “Gee, what a cute brogue,” you have to respond, to adjust. You’re in America and you’ve been labeled “Irish.”

You didn’t have to think about that in Ireland but you’re in the States now, pal. And when you think about being Irish, what comes to mind? If you’re a cub of the Celtic Tiger will you go along with St. Edmund Campion and admit that you are, indeed, amorous and ireful? Whoopee and musical beds and there is Mother Church in the comer, her head hung, weeping.

Irish-American? That’s another story. Here is virgin territory for the social historian, not the history of Irish Americans, but their relationship with the folks back home. Of course we brought baggage from Ireland. We brought our stories, our songs, our hymns, our sense of place. We barged into the Brahmin enclave of Boston and never took no for an answer. Daniel O’Connell had told us, “Organize, organize,” and if we were slow to act in Ireland, we seized the day in the United States. We dominated politics and the church and set up an educational system of parochial schools and universities which seems to have escaped the attention of our historians.

Simply put, we saw power and took it.

All along we looked back over the years and across the ocean and deferred to the history, the tradition, the land. Look at the richness of Ireland’s culture, all that history, all that suffering, and a song for every event, every battle, every lost love, every sailing away, every drop to ease the pain. At any party in the States the Irish would sing loudly, merrily, endlessly, while their Irish-American brothers and sisters served the drinks and, in their ignorance of their own achievements, wished they’d been hurt into that kind of music.

Then something happened. Damn! Who is this Michael Flatley, this Seamus Egan, this Eileen Ivers, this Joanie Madden and her Cherished Ladies? And who do they think they are, coming to Ireland and, not only sweeping the competition but, talented, pushing their way into the culture of their ancestors? Who is this Mick Moloney, a Limerick man at Villanova University, who gives equal time and grace to the musical traditions of the narrowbacks?

The Atlantic has become a puddle which poets and musicians leap without a second thought. Irish-Americans are discovering their own turbulent and rowdy history and the songs that go with it. They’re throwing the overalls in Mrs. Murphy’s chowder and splashing Finnegan with whiskey to wake him.

Michael Patrick McDonald takes us on a heartbreaking tour of his South Boston family while William Kennedy guides us through the heart and soul of an Irish, and American, Albany.

So…what is it to be Irish nowadays?

It is to live on either side of the Atlantic Ocean, or anywhere else, and to be able to say, “You’ve come a long way, Michael or Maggie. You’ve come singing and dancing and remembering St. Edmund Campion, you may be ‘mirrors of holiness,’ ‘great almes-givers,’ and ‘passing in hospitalitie.'” ♦

_______________

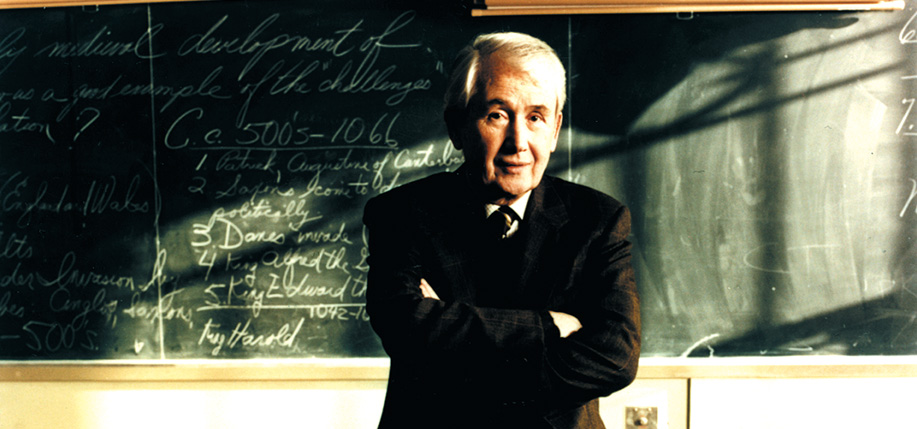

After a long career as a schoolteacher, Frank McCourt won the Pulitzer Prize in 1997 for his memoir Angela’s Ashes.

Leave a Reply