Even now, here 30 years since, when I turn to the southwest in Ennis from Shannon, and head out on the peninsula that ends at Loop Head, and somewhere on that road get my first wind of turfsmoke, I remember the first time and the sense that I had then of coming home.

“The name’s good,” the man in the customs hall had said, letting my bags pass without a look. I had a hundred dollars in my pocket, the stub of a one-way ticket from Detroit to Shannon, and the whereabouts of my cousins, much removed, committed to memory: Moveen West, Kilkee, County Clare. It was February 1970. I was 21.

My knowledge of people and a home in West Clare “on the banks of the River Shannon” began over Sunday dinners at my grandparents’. To the grace he would recite before turkey and gravy, my grandfather would add, “And don’t forget your cousins Tommy and Nora Lynch on the banks of the River Shannon, don’t forget.” Then we would sit and pass the dishes, the people and place names familiar and mysterious, like prayers we learn to say before we learn the meaning of them.

He himself had never met them – Tommy and Nora, his first cousins, son and daughter of his father’s brother. His father, my great-grandfather, another Tom Lynch, had left West Clare in the 1890s and come to Jackson, Michigan, for steady work in the prison there and the Studebaker factory. He never returned to Ireland. Nor had my grandfather or father. I was the first back. My mother’s people, O’Haras from Sligo and Graces from Kilkenny, had lost all interest in or knowledge of their townlands. And my father’s people, most of a century and four thousand miles removed, hung by this little ritual thread of remembrance – Bless us, O Lord…Tommy and Nora…banks of the Shannon…don’t forget.

Some things change and some things don’t. The thatch on that cottage in 1970 gave way to slate, and the great open hearth has been enclosed and storage heaters and back boiler installed. The water that was brought by buckets from down the land and boiled in the coals runs hot and cold now in the sink and shower. There are more appliances and less cooking somehow. There’s a phone and a toilet and a TV – the great civilizers of the 20th century. But the flagstones are the same, the thick walls, the deep windows, the wind off the ocean, the dark of night, the cattle in the cow cabins, the turf in the shed, the names of the families up and down the road.

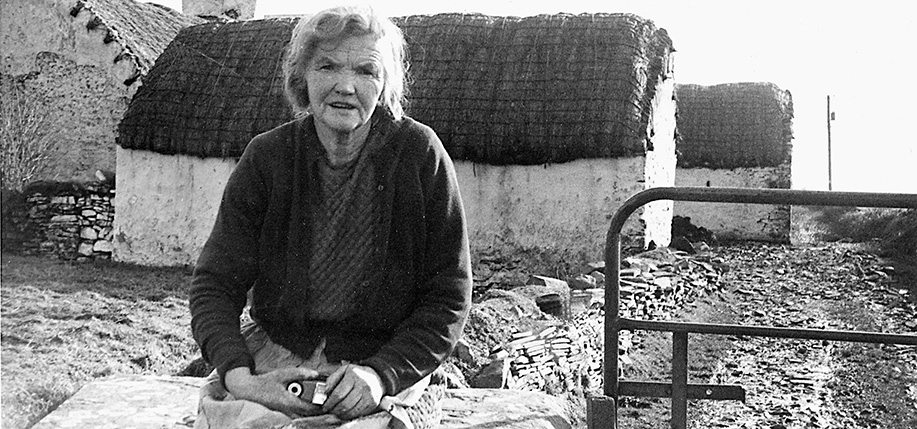

Tommy died the year after I met him and Nora lived on, a sound woman on her own there until she died almost 90, in 1992. She changed my life. I think I changed hers. I was her Yank, the one who came back, albeit generations late, and kept coming back year after year, with news of America and her American family. And after her brother died she made her first trip to Dublin to get her visa to go herself and see the place where her sisters and cousins had gone. She made five trips in all to the States, the last the summer before she died. She left the house, her home, to me. It was the home my great-grandfather left a century ago and never saw again. And sometimes sitting in the west window there, I see what that Tom Lynch must have seen, looking out at Newtown and the sea coming up in Goleen and the mouth of the Shannon agape in the southwest – a topography that he looked past for his future and the one I look on with a sense of the past. He left Clare with a tin footlocker with TOM LYNCH – WANTED on it. He left with most of his life in front of him but few choices. I return, twice a year, most years now, with most of my life lived but with many more options. I get The Irish Times online and The Clare Champion in the mail. I bring tea back in my suitcase and get books mailed from Kenny’s in Galway. I have email and phone calls from my neighbors in West Clare. Here or there I’m never far from home.

And sometimes, sitting there, warming my hands to the fire, I think of Nora sitting, warming hers, and remember how her faith was informed by doubt and wonder. “I wonder if there’s anything at all,” she’d say. “I wonder if He hears us when we pray.” Nora had a fierce heart, long years and the sense that life repeats itself. “‘Twas Tom that went,” she’d say, “and Tom that would come back.” ♦

_______________

From Bodies in Motion and at Rest by Thomas Lynch ©2000, W.W. Norton & Company. Reprinted with permission.

Leave a Reply