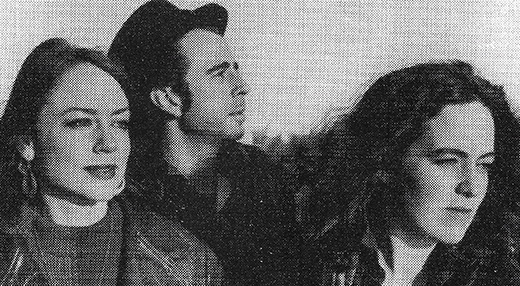

The musicians who made being Irish “cool.”

The year was 1985. At roughly about the same time that U2’s Bono was stage-diving into the massive crowd gathered for Live Aid, the charity concert organized by former Boomtown Rat Bob Geldof to help eradicate world hunger, the first issue of Irish America was being prepped to roll off the presses.

It’s been a wild 15 years for Irish music, and Irish America has been there to chronicle it for you.

Some might argue that Irish music is on a downswing – after all, U2 has been around for two decades now, and there appears to be no heir apparent. But there is strength in numbers, and the amount of Irish artists making fine music has never been greater.

1983’s album War put them on the map, but that 1985 performance at Live Aid introduced U2 to a global audience. They exuded strength and warmth that day – Bono’s chants of “No more” during “Sunday Bloody Sunday” were echoed by the hundred thousand strong in Philadelphia’s aging football stadium, and countless others watching at home. They followed that up with 1987’s The Joshua Tree, a watershed album that contained powerful hits like “Where the Streets Have No Name” and “With or Without You,” landing the band on the cover of Time magazine. Some uneven efforts followed: strong albums such as Rattle and Hum and Achtung Baby were countered by duds like Pop and Zooropa. U2 fans are eagerly awaiting the release of their newest, tentatively scheduled for an autumn 2000 release, and many see it as a make-or-break statement.

At around the same time as Live Aid, a Londoner-by-way-of-Tipperary was writing songs that would enter the eternal Irish music canon. Shane MacGowan, who had skulked around London singing in punk bands, formed the Pogues with Philip Chevron. Songs like “Fairytale of New York” and “Sick Bed of Cuchulainn” were traditional music on methamphetamine, and spoke eloquently of the Irish emigrant experience in England, which was often rough, low-paying, and lonely.

Sadly, the Pogues imploded, but MacGowan continues to make hard-hitting music with his new band, The Popes.

On this side of the Atlantic, a Wexford expat and a Brooklyn cop were chronicling the American emigrant experience just as eloquently. Larry Kirwan and Chris Byrne formed Black 47 in 1989, speaking to the “new Irish” who were often illegally employed as laborers, nannies, and barmen. They got thrown out of every joint they played in until they landed a residency at Paddy Reilly’s, a pub on the East Side of Manhattan. Their gigs there became the stuff of legend, attracting figures from the celebrity and literary worlds. But they steadfastly held onto their residency at Reilly’s, opting to stay true to the regular folks who supported the band.

Byrne recently departed Black 47 to devote his full-time efforts to his new Seanchai and the Unity Squad, a driving mix of Irish music, hip-hop, and politics.

Indeed, Paddy Reilly’s became a sort-of musical laboratory for original Irish music in the ’90s. Innovators like Pat McGuire’s Speir Mor, Pierce Turner, and Susan McKeown’s Chanting House all had steady gigs there.

Chanting House was particularly fertile: one-time flautist Joanie Madden went on to solidify Cherish the Ladies, and guitarist John Doyle and multi-instrumentalist Seamus Egan formed Solas. Fiddler Eileen Ivers was a star in Bill Whelan’s Riverdance show, and she had a career breakout in 1999 with her magnificent album Crossing the Bridge.

The singer / songwriter was alive and well, too. Christy Moore has often been described as “Ireland’s Woody Guthrie,” and his self-titled 1990 release, featuring “Ordinary Man” and “Lisdoonvarna,” was one of that decade’s best. Brother Barry – Luka Bloom – impressed with Acoustic Motorbike in 1992. Eleanor McEvoy wrote a resonant anthem of loss with 1991’s “Only a Woman’s Heart.” Mike Scott moved his Waterboys to Galway in the late ’80s, and scored a winner with “Fisherman’s Blues.”

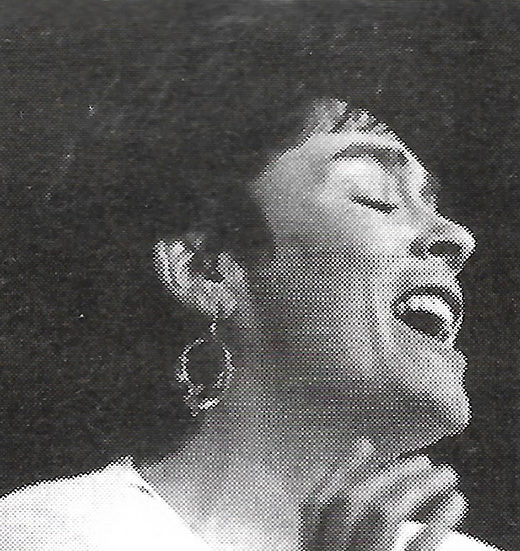

In 1988, an angry, bald-headed woman came roaring into the party, and hasn’t left since.

Sinead O’Connor impressed with her debut The Lion and the Cobra, a swirling maelstrom of funky, aggressive songs. Her follow-up, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, was just as impressive, but she was better known in the ’90s for media stunts (ripping up a photo of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live, declaring herself a priest) than for her music. But this year’s Faith and Courage is impressive, and may see O’Connor back on a focused musical track.

The Chieftains solidified their role as Ireland’s premier musical ambassadors. Their 1988 collaboration with Van Morrison, Irish Heartbeat, was a classic treatment of some well-known standards. And The Long Black Veil, released in 1995, proved the group could rock with the likes of Sinead O’Connor, Tom Jones, and the Rolling Stones. Van Morrison provided some great moments as well: 1990’s Enlightenment and 1997’s The Healing Game are modern classics. He was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1993.

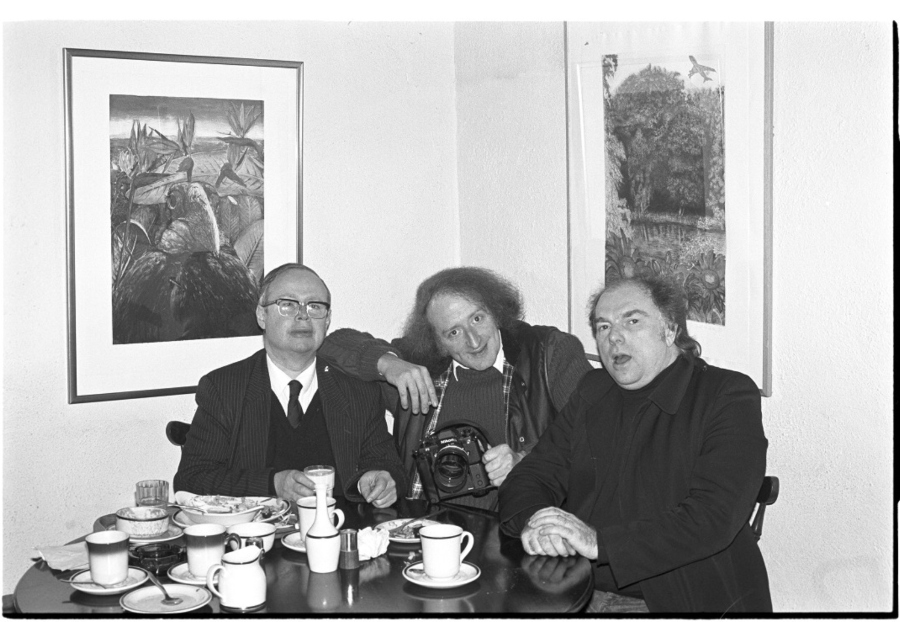

Photo: © Bobby Hanvey Photographic Archives via Boston College Digital Commonwealth

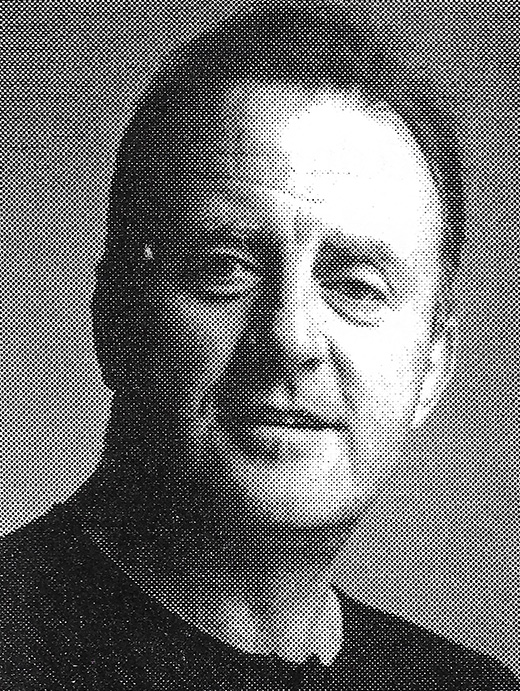

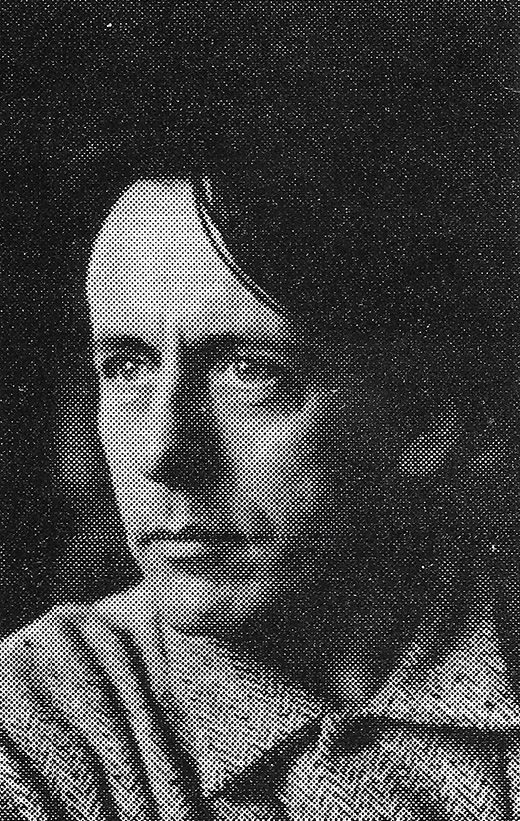

Sadly, two of Ireland’s most dynamic rockers passed on in the last decade and a half. Phil Lynott, the bass playing founder of Thin Lizzy who penned rock classics “The Boys Are Back in Town” and “Jailbreak,” died in January 1986 at the age of 36. And brilliant guitarist Rory Gallagher, whose Calling Card album is a blues classic, died in 1995 at age 46.

Shows like Riverdance and Lord of the Dance certainly brought new attention to Irish traditional music. Altan turned heads with their stellar 1990 album Red Crow, and has consistently made fine music, despite the death of founding member Frankie Kennedy in 1994. DeDanann has boasted singers such as Mary Black, Maura O’Connell, and Dolores Keane, and core members Frankie Gavin and Alec Finn continue to innovate, no matter what the shifting lineup is. Accordionist Sharon Shannon has become a modest superstar.

After DeDanann, Mary Black branched out into pop, and had an American hit with her 1994 No Frontiers album. Her latest, Speaking with the Angel, shimmers. Maura O’Connell moved to Nashville, and has embraced country, folk, and American blues. Her 1989 Helpless Heart boasts several gems, and that album’s title track is penned by Paul Brady.

So what does the future hold for Irish music? Certainly the accomplishments listed here are formidable, but many are over a decade old. At first blush, the future might seem grim, as confections such as Boyzone, The Corrs, and Westlife regularly top the charts. But there are innovators in both pop and trad that are making a new noise (see below.)

The next 15 years should be interesting. ♦

_______________

The Irish charts have been a bit bland lately. But the following artists promise to stir things up.

℘℘℘

Jack Lukeman, Metropolis Blue; Label: Razor and Tie

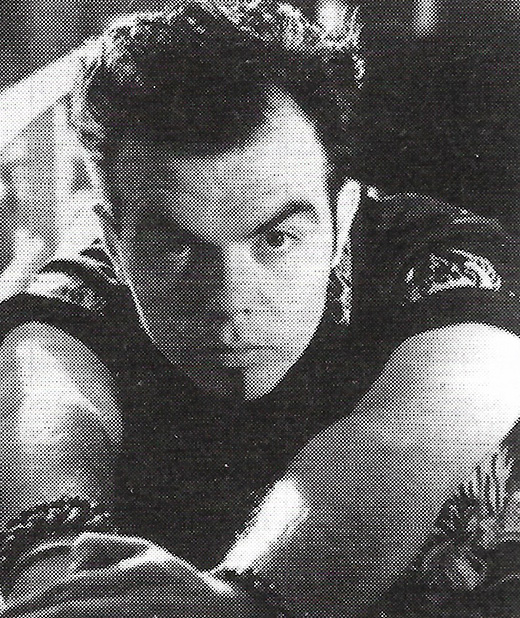

The voice grabs you. A rich, throaty croak, as thick as the fog that rolls across San Francisco Bay and as deep as the mouth of the Liffey. It’s Jack Lukeman’s calling card, and he’s not shy about letting it fly.

His newest release, Metropolis Blue, is a ten-song pastiche of post-punk ballads, ballsy torch songs, and in-your-face art rockers. Dark-alley lyrics and tremolo-dripping guitars give this songs a noirish quality: standouts are the foreboding “Taste of Fall” and the fuzzy, grab-you-by-the-lapels “Crazy.” “Ode to Ed Wood” is a gender-bending tribute to the late B-movie pioneer, and “Metropolis Blue” engages with some loping, hep-cat swing.

Songwriting partner / guitarist David Constantine leads a crack band that plays these songs with muscle and panache.

But it’s Lukeman’s voice that’ll make the greatest impression on you. He growls, he booms, he soars, and most importantly, he draws from within. Lukeman certainly cultivates the dark outsider image – shoe-black hair and some 22nd-century facial hair have put the Athy, County Kildare-born lad on some “sexiest man in Ireland” lists. But Lukeman puts substance before style, and Metropolis Blue is a strong and intriguing debut.

Part Jacques Brel, part Jim Morrison, Jack Lukeman appears to have a very large upside. Wonder when we’ll see him perform a VH1 duet with Tom Jones.

Kila, Lemonade and Buns; Label: Green Linnet

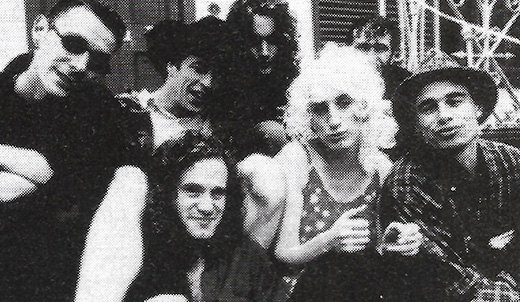

There’s no denying that the members of Kila are stellar musicians, and bring a worldly sensibility to the songs they perform.

But if there’s been one disappointment about the Dublin-based septet, it’s that their recorded performances have paled in comparison to their live set. A Kila show is a strange and marvelous thing: the group is renowned for whipping a crowd into a swirling, dancing frenzy. Their previous effort, Tóg é Go Bog é, was impeccably played, but it didn’t quite capture that elusive Dionysian vibe they stir up at their shows.

That’s not the case with Lemonade and Buns, which has a glorious live feel. Melodies and polyrhythms dart and dance throughout, taking the listener on a delightful magic carpet ride. Multi-layered percussion drives “An Tiomanai,” and “Spicy” adds an Eastern flavor to the propulsive mix. Jazzy chord changes mark the hip “Rachel’s Reel.”

But it’s not all up-tempo revelry. “The Liosterin Waltz” and “Andy’s Bar” are beautiful, pensive instrumentals – melody, countermelody, and harmony meld like Celtic knotwork. “Ce Tu Fein” is mournful and haunting. Kila has crafted a gorgeous document – Lemonade and Buns is sharp, hip, and delightful.

Paddy Casey, Amen (So Be It); Label: Sony / Columbia

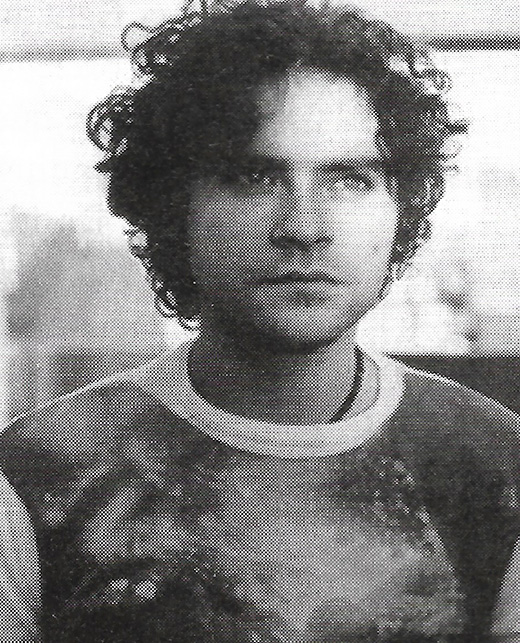

Twenty-four-year-old Paddy Casey got his start busking on the streets of Dublin when he was just 12, bashing away on a battered acoustic guitar on Grafton Street.

The experience served him well. On Amen (So Be It), Casey offers up an engaging selection of brisk, hummable tunes, drawn from his own triumphs and losses. Casey bemoans love’s fuzzy rules in “Everybody Wants,” “Fear” sees Casey praying that she’ll stay. Some of the songs are hushed (“You Can’t Take That Away from Me,” “Rainwater”); others lash out with a full band behind him (“Ancient Sorrow,” “It’s Over Now”) but they mostly stand up.

I dare you to come away from this album without humming “Whatever Gets You True.” Sure, Casey’s a bit ponderous in spots – how many 24-year-old songwriters aren’t? – but Amen (So Be It) is an optimistic, encouraging debut. ♦

Leave a Reply