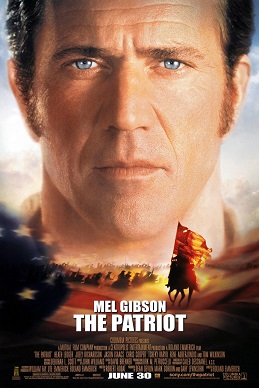

Round two of Mel Gibson’s war with the British.

℘℘℘

Jack L. Warner once said he hated the kind of movie in which the hero “writes with a feather.” Hollywood’s aversion to the quaint details of a distant historical period helps account for the scarcity of films dealing with the American Revolutionary War. But reluctance to alienate Great Britain probably had more to do with Hollywood’s longtime neglect of this fascinating historical subject. When Frank Capra wanted to film Maxwell Anderson’s play Valley Forge in the late 1930s with Gary Cooper playing George Washington, Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn vetoed the idea because he did not want to cast a bad light on England while it was under the threat of war from Nazi Germany.

During the Vietnam War, when the very concept of patriotism was under attack in America, John Ford and Capra decided to team up to film Valley Forge as a low-budget production for the upcoming 1976 U.S. bicentennial celebration. Their proposal stressed that Valley Forge would not be simply a flag-waving spectacle or an anti-British tract, but a human drama like A Man for All Seasons or Patton, appealing to audiences of every political persuasion. Columbia, however, was preparing to make what Capra called “that awful goddamn thing, that musical about the Revolutionary War [1776],” and refused to part with the Anderson play for fear of competition. After squandering those two opportunities to make Valley Forge into a major cinematic event, the studio turned it into a forgettable television movie.

Ironically, it is Columbia Pictures, now under Japanese ownership, that gives us the $100-million-plus Revolutionary War film The Patriot, a film so unabashedly anti-British that it provoked cries of indignation in the U.K., where it predictably flopped at the box office. Why has England become fair game for criticism by Hollywood during the last few years? In a further irony, with the British actively engaged in the peace process in Northern Ireland, only now can the political issues be painted in lifelike shades of gray, since it is no longer a vital part of American policy to treat the British as sacred cows. Furthermore, the end of the Cold War has made both Britain and Ireland less important strategically to American military planners, easing the pressure on Hollywood to be unambiguously Anglophilic.

Mel Gibson did not direct himself in The Patriot – that job went to Roland Emmerich – but the film seems an extension of Gibson’s own 1995 epic Braveheart, which won him Oscars as both producer and director. The stirring saga of Scottish patriot William Wallace, Braveheart is a powerful cinematic statement against the British colonization of Scotland in the 13th century (it was filmed in both Scotland and Ireland). A native of Peekskill, New York, Gibson is of Irish descent and was named after St. Mel’s cathedral in Longford, Ireland. He moved to Australia with his parents when he was 12. Gibson clearly has strong feelings about British colonialism and a genuine empathy with those who fight for national freedom. His complicated background also informs these two films’ focus on quests for national identity.

At the beginning of Braveheart, superbly written by Randall Wallace, the film’s narrator, Robert the Bruce (Angus MacFadyen), remarks, “Historians from England will say I am a liar, but history is written by those who have hanged heroes.” Nevertheless, the film freely fictionalizes various episodes – for instance, England’s King Edward I (Patrick McGoohan) did not throw his son’s male lover out a window – and imaginatively fills in many gaps in the historical record.

One of the most memorable scenes in Braveheart involves Irish conscripts in the king’s army. When asked if he wants to send in his archers to make the first assault on Wallace’s men, Edward replies that arrows are expensive. “Use up the Irish,” he says, “for they cost nothing.” The Irish charge the Scots, but both stop in the midst of the battlefield, joining forces to turn their wrath back upon the British. While the film portrays the British in an entirely negative light, the characterizations of the enemy in Braveheart still seem more three-dimensional than those in The Patriot.

Subtlety is not Roland Emmerich’s forte; the last two movies he directed were Godzilla and Independence Day. But he has a strong visual sense, and he and cinematographer Caleb Deschanel create vivid tableaux of the Revolutionary War period. Production designer Kirk M. Petruccelli and costumer Deborah L. Scott convincingly take us back in time. Yet the film has little to do with the issues of the war; it’s more about the Gibson character’s communion with “his inner savage,” as J. Hoberman put it in his Village Voice review.

Gibson’s Benjamin Martin is a well-to-do planter in South Carolina, a widower with seven children and a bloodied veteran of the French and Indian War. As a delegate to his colony’s assembly, Martin refuses to vote in favor of the Declaration of Independence. Reluctant to get involved again in warfare because he fears his own dark instincts, he wants peace at almost any price until the price proves to be the life of one of his sons. Benjamin is the kind of conflicted, self-centered warrior to whom a modern audience can relate, someone un-concerned with issues of nationalism or self-sacrifice.

Much of the blame for the ahistorical nature of The Patriot must be laid at the hands of its screenwriter, Robert Rodat. Rodat received an Oscar nomination for his work on Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, but his screenplay is the weakest element of that powerfully directed World War II film. Its central situation – a platoon sent to rescue a soldier whose three brothers have been killed in combat – never actually happened, but was cobbled together from other incidents. Rodat concocts a far-fetched moral dilemma that seems irrelevant to the war’s larger issues. He puts the climax of the war (the D-Day landings) at the beginning of the film, making it seem progressively less compelling. And he ignores the role of the British on D-Day, concentrating entirely on the American assault on Omaha Beach. Ryan ends with a gung-ho battle scene whose old-fashioned Hollywood heroics undercut the realistically somber tone of the magnificent opening sequence.

A similar tendency to embellish and exaggerate historical incidents when the actual events can hardly be topped for drama also mars The Patriot. Here the screenwriter’s historical tunnel vision is even more problematical, since for a contemporary audience unfamiliar with the Revolutionary War, any film on the subject must be, among other things, a history lesson that clarifies without oversimplifying.

The Patriot makes stabs at a balanced attitude toward the British. Their commanding general, Lord Cornwallis (Tom Wilkinson), is a complex and not entirely unsympathetic figure. Cornwallis urges restraint in the conduct of the war (“These colonials are our brethren”) before reluctantly sanctioning brutal tactics of his subordinate, Colonel William Tavington (Jason Isaacs). Cornwallis’ traditional faith in pitched battles is overcome by the colonials’ use of guerrilla tactics, a situation reversed two centuries later when the technologically superior U.S. forces lost the Vietnam War to Viet Cong guerrillas.

“These rustics are so inept – nearly takes the honor out of victory – nearly,” Cornwallis says with a smug laugh before getting his comeuppance. Then he wonders, “How could it come to this – an army of rabble.”

Tavington is luridly portrayed as a cold-eyed, sadistic psychopath. By indulging in such a melodramatic portrayal, the filmmakers surrender to the same temptation that fatally flawed America, D.W. Griffith’s 1924 film on the Revolutionary War. America has a wildly melodramatic British villain played by Lionel Barrymore, whose tedious scenery-chewing blunts the effect of Griffith’s impressive battle scenes. Such hissable villains obscure the genuine evils of colonialism by reducing them to the character flaws of individuals.

Tavington is based on Colonel Banastre Tarleton, a British cavalry officer described as “hated and dreaded” in Barbara W. Tuchman’s 1988 book on the Revolutionary War, The First Salute. Tuchman reports that Tarleton was “valued highly by Cornwallis as the spearhead of his army…. Tarleton’s heavy dragoons trampled fields of corn and rye while his and [Benedict] Arnold’s raiders plundered and destroyed the harvested tobacco and grain in barns, spreading devastation. Tarleton was charged with driving cattle, pigs, and poultry into barns before setting them afire. He was known as ‘no quarter Tarleton’ for his violation of surrender rules in the Waxhaw massacre, where he had caught a body of American troops that held its fire too long before firing at fifty yards, too late to stop the charging cavalry. After surrender, they were cut down when Tarleton’s men, let loose to wield their knife-edged sabers, killed a total of 113 and wounded 150 more, of whom half died of their wounds. Enmity flared higher when the tale of the Waxhaw spread throughout the Carolinas, inflaming hatred and hostility and sharpening the conflict of Loyalists and Patriots.”

But such real-life atrocities aren’t terrible enough for The Patriot. Hoberman noted that the film sets out to “Nazify the British army,” which is probably the real reason it raised British hackles. Taking Tarleton’s barn-burning of animals a step farther, The Patriot has Tavington burn American villagers alive in their church. This scene appears to have been based on the infamous 1944 burning by the SS of a church filled with more than four hundred women and children in the French village of Oradoursur-Glane. Such an anachronistic borrowing may reflect director Emmerich’s desire to distance himself from the villainy of his native Germany. Columbia’s press notes go out of their way to state that Emmerich was “born in Germany ten years after the end of World War II.”

Attempting to compare any other form of villainy to the ultimate evil of Nazism usually backfires. If one searches for a comparison with Nazism, Britain’s consciously genocidal policies during the Great Famine would be more apt. The ahistorical reference in The Patriot takes the viewer out of the movie and inadvertently causes the opposite of the effect intended. Perhaps that helps explain why the church-burning sequence is curiously unmoving. Filmed mostly in long shots at sunset, it tends to aestheticize what should be overwhelmingly horrific.

The Benjamin Martin character was based on the celebrated South Carolina guerrilla fighter Francis Marion, known as “The Swamp Fox” because he conducted his missions from a hideout on a river island and Tarleton referred to him as “this damned old fox.” But the Marion character was fictionalized when the filmmakers did some more research and learned that he was a slave owner. According to conventional Hollywood wisdom, a film’s protagonist, however brutal, still has to be “likeable.” Although having a Southern slave owner fight for liberty would add a layer of complexity to the film by acknowledging the contradictions of America’s origins, it was deemed advisable to soften the character.

As a result, the African Americans who work on Martin’s plantation are depicted as free men, happy to toil under his benevolent hand, even if some are killed for their allegiance to him. There is a slave who fights in Martin’s irregulars to win his freedom, but Spike Lee has rightly criticized the film’s minimizing of the importance of the slavery issue. The most absurd scene is a party held by free blacks for Martin’s family, a hoedown improbably celebrating racial harmony. To make matters worse, every time a black character appears, he or she is given corny, self-conscious speechifying about how a “whole new world” is coming. Unfortunately, The Patriot‘s view of American race relations would seem overly rosy even if the film were set in the year 2000.

The film’s true focus is on the tension in Benjamin Martin between savagery and civilization, a theme it shares with such classic Westerns as Ford’s The Searchers and Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. This aspect of The Patriot is more interesting, if not entirely successful. Martin is guilt-ridden over the savagery he exhibited when he led a revengeful slaughter of French soldiers during the French and Indian War (what he did to the Indians isn’t mentioned). Once he sets himself loose again, Martin becomes a killing machine like Wallace in Braveheart, but with less sense of a greater purpose. Neither film shies away from the brutality of war, but while the graphic violence of Braveheart is almost always convincingly realistic, The Patriot too often seems preposterously Rambo-like.

Perhaps the makers of The Patriot felt it necessary to exaggerate British villainy in order to justify the complementary violence of the American side. It’s rare that Hollywood asks the audience to face up to the ugly realities of war as waged by Americans, particularly when it involves our Founding Fathers. The great film about the Revolutionary War has yet to be made. The consolation is that there is still so much of the story left to tell. ♦

Leave a Reply