My south London schoolmates and I struggled with our Irishness during the 1970s. Nearly all of us had Irish parents who had settled in England in the 1940s and 1950s, but we had been born and raised in London. Did that make us English or Irish?

Most of us made regular summer trips to Ireland, looked Irish, even knew a few Irish words. Some of us just felt Irish – all our relations were Irish, as were most of our parents’ friends, our priests, and our teachers.

But identifying yourself as Irish was problematic. The I.R.A. was attacking London – in the 12 months starting with October 1974, the British capital was bombed, on average, once a week. The explosions forced us to choose whose side we were on. To many of our teenage minds, being Irish meant being experts on Ireland and supporting the I.R.A.

We tested each other on Irish trivia – what license plates do they have in Wexford? How do you say the “Hail Mary” in Irish? Is Bomber Liston a Kerry footballer or an I.R.A. man? (One kid impressed the playground by brandishing the leather bracelet his uncle, a prisoner in Long Kesh, had made for him.)

We learned the words to rebel songs and read books about Easter 1916, thinking it made us more Irish. Our special hero was I.R.A. leader Seán Mac Stíofáin, a London Irish boy who’d been imprisoned for Republican activity before he’d ever even set foot in Ireland. In the early 1970s he was the head of the Provisional I.R.A., one of us, Cockney Irish.

On a school trip to Ireland in 1976 some of us made the pilgrimage to Dublin’s G.P.O., genuflected at Wolfe Tone’s grave, and stood to attention for the Irish national anthem in a Limerick cinema after all the locals had bolted out the door.

We insisted to kids in Laois that we really were Irish, despite our accents. “Look at the heroes of 1916,” we said smugly. “James Connolly, Tom Clarke, Eamon de Valera – none of them born in Ireland.” The Irish kids laughed at our pretensions.

Some of us joined underage Gaelic football teams in London. In 1979, I captained the “county” of London against New York in an early round of the All-Ireland Championship (our team barely touched the ball). We were Irish wannabes, derided by Irish relations as “Plastic Paddies” for not being the genuine article.

And London Irishness was different from Irish Irishness or American Irishness. Cousins in Dublin or Boston weren’t surrounded by English people, and couldn’t understand why it was difficult – even dangerous – for us to wear shamrocks on St. Patrick’s Day. For our parents’ generation, the bombings made things even more complicated.

Their accents immediately identified them as Irish in a city where Irish people were killing civilians. They were keen to show suspicious Londoners that the I.R.A. didn’t represent them, and missed few chances to denounce the bombings. “We don’t bite the hand that feeds us,” said many Irish people who had earned livelihoods in England for 30 years. Irish clubs across London banned I.R.A. songs – modern or ancient – from their dances lest there be any doubt about their loyalties.

On weekdays my dad worked as a postman, and when one of his workmates had his fingers blown off by an I.R.A. letter bomb we were scared he would be next. At weekends he moonlighted as a cabbie, and we waited in silence for his safe return every time a news flash interrupted evening television to report another random bombing in central London.

When we reached our late teens, most of my schoolmates and I were faced with the Great Passport Decision. Those of us with Irish parents had the choice to be British subjects or Irish citizens. It was an official, legal choice. You could be one or the other.

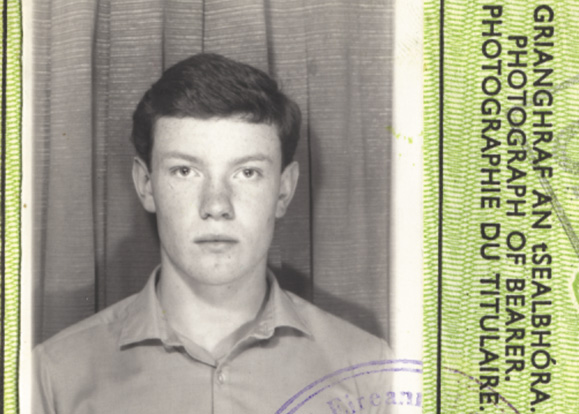

Some opted for an Irish passport because it was a few pounds cheaper, but for others it was a decision loaded with political significance. The weekend of my 18th birthday, Bobby Sands began his hunger strike, and I chose an Irish passport.

The arrival of an Irish passport was the ultimate validation of our claims – there it was, in green and white, our national status legally declared. True, we had not been born in Ireland, but we had chosen Ireland in a way our Kerry cousins had never done, and surely that made us even more Irish?

A few years later, things became easier for London Irish teenagers. Random bombings in the city were rare, and while militant Republicanism still has its pull for some youngsters (Londoner Diarmuid O’Neill joined the I.R.A., and was shot dead by police in Hammersmith in 1996), modern Irish London offers more than a miserable anti-Englishness.

The success of The Pogues helped legitimize being Irish in London, and even made it trendy, while soccer stars like Tony Cascarino and Andy Townsend replaced Mac Stíofáin as the new Cockney Irish heroes. Today’s London kids with Irish parents are free from the edginess of the 1970s, and now the Irish or English dilemma is far more likely to be argued in the context of sport or music than political violence.

I left London many years ago, and now live in Ireland, more at home than I’ve ever felt in my life. Living in Ireland is all I hoped it would be when I used to dream of it 25 years ago. I play soccer in the local sports club, where I’m known, inevitably, as “the English fella.” ♦

Deep! Thank you for those insights. My mom’s family is Irish American. for me tudying The Troubles has a disturbing echo in America today.

As a proud ‘plastic paddy’ myself, born and raised in South London I prefer your ‘cockney Irish’ Irish expression and will use the term from now on, really enjoyed reading this so thank you