Three generations return home.

℘℘℘

A summer journey fills the pockets with scraps of nothing and bits of everything. The boarding coupon for seat 33F. A receipt for two crunchie bars, a ticket from that play in Galway, a few 20-pence pieces, a flat lake stone for skimming. And that slip of paper, scrawled with the name Dad mentioned as we traveled through Ireland in July.

“No one slept. Eight of us in the one car. We drove all night from Sneem to Cobh, May 19, 1949,” said Dad. “The tender left for the ship at 11 a.m. It was an old troop carrier. Frank sent me the ticket from Rhode Island.”

“Wait a minute. Who had the car?”

“A fellow named Sonny Mountain drove us,” said Dad.

I had never heard of Sonny Mountain, indeed, had never inquired about the details of Dad’s voyage from Ireland to America. To hear the driver’s name suddenly gave the moment an insane cosmic heft. What if Sonny had been stuck on the day at his regular job driving the turf truck to the bog, and Phil Dwyer had missed that boat, thus throwing off the life-calendar that put him in an American G.I.’s uniform a couple of years later at the Caravan Dance Hall on 59th Street, in time to sweep Mary Molloy around the floor and the two of them into each other’s lives?

“I suppose his real name was Sonny Sullivan,” said Dad. “But Sonny Mountain was what he was always called.”

Of course. So many O’Sullivans roam southwest Kerry that they are nicknamed by the color of their hair, or the place where they live, or a grandfather.

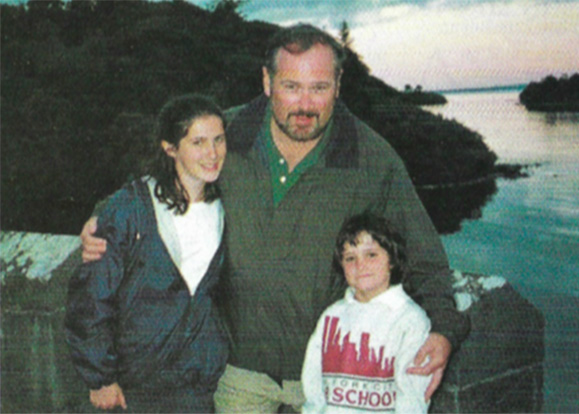

In the back of the car, my girls Maura, 14, and Catherine, 7, dozed. The night before, a string of unflyable planes pinned us to the ground in New York for hours. That made it all the sweeter, on a sparkling July afternoon in the first year of the new century, to make Ireland once more.

“Counting the time at the airport waiting, we were eleven hours traveling,” noted my father, more in wonder than in complaint. “That was as long as it took us 39 years ago to get here.”

With that, the grandchildren stirred in the back, wondering what a span of 39 years could possibly be like. The smaller one spoke to me. “Daddy,” asked Catherine. “How old were you when Grandpa brought you here the first time?”

I was four, and my brother Pat was seven in 1961, when Phil Dwyer carried two of his New York children home to visit his own father in Kerry and our mother’s people in Galway. That air journey across the Atlantic, however long it lasted, has vanished from memory. So, too, has my infected thorn, a famous howling trauma in its day.

That time, that trip, was threaded into the events that could be gripped by a small boy’s hand: the tedious magic of butter rising from a churn; the number of potatoes, spaded from the garden, that filled a pail; the tantalizing horror of otter pelts curing on wooden racks. The days ended with the old grandfather saying, “Aaay-zee now” and tip-tapping an ash stick as he herded cows and led American grandsons down the lane. I still can hear the creak and water dip of oars, pulling us into Kenmare Bay on a hushed evening fishing trip. And lodged somewhere between my wrist and elbow is the memory of a tug on a fishing line, the fight made by an angry, silvery mackerel that someone secretly lipped onto my hook. The proud trophy would be grilled for my breakfast by Aunt Mary.

My parents left rural Ireland more than a half century ago, then found each other in a city of migrants and pilgrims and tourists. For most immigrants, leaving home is like splitting the atom, unleashing waves of energy that propels a generation or two into the future. Phil Dwyer and Mary Molloy raised four sons in rent-controlled Manhattan. You knew you were Irish because everyone was something. That one is Puerto Rican. There’s an Italian. This one’s a Jew. You do not realize, as a child, that these lineages are deep, rich wells; that being Irish or African or Asian is a gift that time gives.

As kids, we dwelled in the émigré culture of Irish dances and Catholic schooling, of civil service for the parents and compulsory college for the children. Later, depending on your line of work, you might imagine Irishness to be some hoped-for trait: a quality of strength or language or craft. It may be any of those or none.

For me, being Irish simply meant we were the children of people who had wandered from country places, beyond the hands of modern clocks, but keeping time all the same. This world still hummed and shimmered when I visited as a child. My parents had grown up in homes where the only running water was spring water, all the lights were kerosene lamps, and men and women were just themselves, canny or foolish, good-hearted or cruel, regardless of their wealth or fashion. If being poor was not a moral failure, then owning or spending fortunes could not be a mark of virtue. It is hard to calculate how often that particular home truth has provided shelter during the gales of trendiness and buzz and temptation that rain on a life in New York.

Two Christmases ago, Dad dove from robust health to feeble in the space of 48 numbing hours. Then he slowly remade himself, finding the spring in his step on long walks in Central Park and the strength in his arms on long drives from the tees at the Moshulu Golf Course. He would go home again, good as ever. Morn would wait in New York. In the summer of 2000, as the Tammany Hall evangelists once said, we seen our chances and took ’em.

We drove north from Shannon, towards a little Galway village called Ower, near a northern finger of Lough Corrib. My father first called on the Molloys in 1954, when he was a recent groom visiting his new brother-in-law, John, and his wife, May.

“I wore a jacket and tie. That was what you did in those days,” said Dad, who favored a zippered gray sweatshirt this time. “John Molloy told everyone I was President Eisenhower’s personal doctor, home from America. A few of them believed it.”

The Molloy home is a kind of spa for the soul, a warm place you feel better for having visited even if there was nothing wrong in the first place. Seamus Heaney could have been speaking of John, May and their tribe when he wrote of a beloved neighbor:

…Being with her

Was intimate and helpful, like a cure

You didn’t notice happening…

– “At the Wellhead”, by Seamus Heaney

“What did you do here when you were a kid?” Catherine asked me.

“One morning I watched Uncle John milking the cows. He didn’t look up from the pail, but he squirted me right in the face from 15 feet away with the cow milk.”

John showed the girls the spot in the front garden where Richard Molloy had set up his forge 200 years earlier. The girls had tea in the garden with our cousin Bernadette, who brought us to a ball alley, three standing walls of an old gristmill. We played handball. Family called to the house. In Galway City we stopped, as always, at Kenny’s Bookstore and Gallery, then ate in an outdoor cafe, swam at Leisureland, and saw the brilliant Macnas performers stage The Lost Days of Ollie Deasy, a version of Homer’s Odyssey built around a vanished all-Ireland hurler. Late in the evening, we had beverages at Greenfield, a little pub on the shores of the Corrib. To the west, the last rays of the sun were tangled in the Twelve Pins of Connemara.

On the long road south to Sneem, in County Kerry, there was more debriefing.

“What did you do in Kerry?” asked Catherine.

“I found the hen’s eggs under the bush, and rushed into the kitchen, and smashed them all,” I admitted.

“Did you get in trouble?” she asked.

“No, they practically gave me a medal. Great-grandpa Dwyer said, `Great mon James.'”

She cackled. “Ye’re a great mon James!” she mimicked.

The old Dwyer farm in Reenroe, outside Sneem, is no longer inhabited; instead, the place inhabits those who knew it. Built on a low bluff over Kenmare Bay, the hull of the first house sits roofless and grass-floored in sunny dignity. Here was the hearth, where the pots hung from a crane over the fire. Here was a kind of cabinet niche built into the stone. Once, a bed had been made from an ornate old wooden door, rescued when the landlord’s big house was torched. Sons and daughters would return from New York or Rhode Island or England with other furnishings. On the same land, two other houses are going back to nature. In the mountains behind us, the bay at our feet, the fir trees planted by Mike, the last Dwyer to live in Reenroe, there was a kind of aching, lonely grandeur.

“But what games did you play, Grandpa?” Catherine asked.

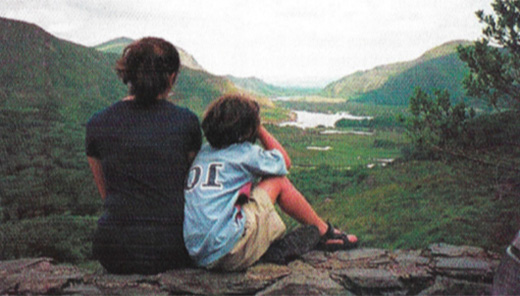

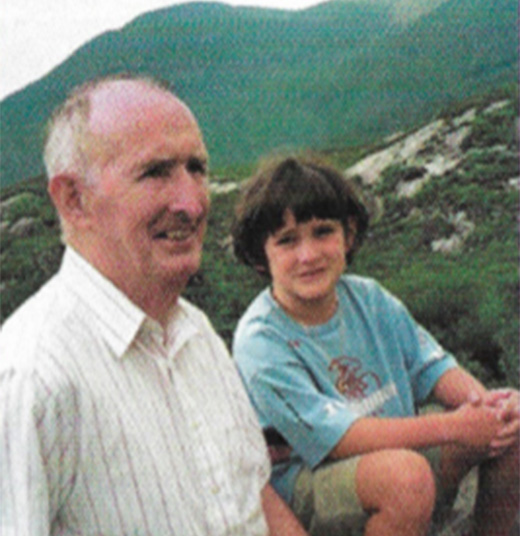

He plucked a purple flower with a big bell mouth, and showed her how to make it pop. We climbed down to a tiny harbor called Bannow, and found little periwinkles on the rocks. At a strand, we scooped up a baggie of coral sand to take home. Dad sat on a rock with Maura and told her who had been here, names and ranks, destinations and destinies. From the driftwood of wrecked ships, they had salvaged nails to build the last house. In the long winter nights of World War II, when even candles and kerosene were out of reach, they had burned strips of bog deal in Reenroe, freeing the light trapped in the ancient oak.

The July night sky was clear as January. At breakfast, I reported to the children on the dizzying pinlights of low planets, satellites, a shooting star.

“Did you make a wish?” asked Catherine.

“I did and you were in it,” I said.

“I hope it included me growing two feet taller.”

In Sneem, the girls ran off for chips with newly-met cousins. We strolled past the town museum, a collection of farm tools and lost jars and unusual papers. A great, roaring Kerryman named Tim O’Reilly hoarded these things over the years, each one pedigreed with a yarn.

“Come here now and I’ll show ye something very interesting,” said O’Reilly.

He pointed to a blurred photograph on the wall, eight people dressed for travel.

“Can ye name anyone in that picture?” asked O’Reilly.

No, I said.

“I’ll give ye a clue. That woman is my sister. That fellow there, he is called Sonny Mountain.”

Sonny Mountain. The unknown but unforgotten wheelman who made it all possible.

“Is this in Cobh?” I asked.

O’Reilly nodded.

Dad stood next to me, gazing at the picture.

I’m looking for the face I had

Before the world was made.

– “Before the World Was Made”, by W.B. Yeats

He had been a young man at the time, and he had not yet left Ireland nor returned to be hailed on a country lane in Galway as Eisenhower’s personal doctor; had not met and married, fathered and grandfathered; the rays of his life had not fanned out.

Someone had kept this forgotten old photograph for half a century. In the back row I could see Uncle Mike and Aunt Ab, who had come from Sneem to Cobh to wave goodbye. The date was May 19, 1949.

And yes, there, first row, far left was Phil Dwyer, a ticket to America and $5.90 in his pocket, ready to board the boat. It was nothing more than a fuzzy old picture of an atom, in the instant before it split. ♦

_______________

Jim Dwyer, a columnist with the New York Daily News, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1995.

Leave a Reply