As all those who read this column know, my Da loved being Irish. He sang all the songs, craved potatoes and strawberries, and cooked huge breakfasts every Saturday morning. He loved words, mesmerized people with his seanachie storytelling and had merry blue eyes that always seemed to be twinkling over some private joke. He was fiercely patriotic and prone to religious debating. His brothers and cousins were sportsmen — jockeys, hockey players and boxers -and he even climbed into the ring himself for a brief period while in the air force during WWII. Now and then, he liked a drop o’ the crature too.

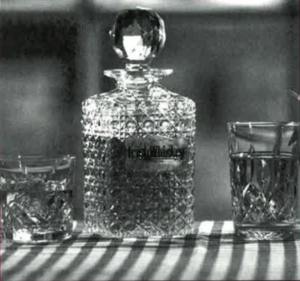

Whenever guests came to dinner, before we sat down to eat, Dad broke out the Irish whiskey and our special tumblers which were reserved solely for the purpose of whiskey sipping. As he poured the amber liquid, the cut crystal sparkled. When everyone toasted each other, the glasses clinking sounded like little bells. With the naivete of youth, I was awed by such ceremony and thought that the people must be really important. It was many years before I learned that sharing a glass of whiskey with visitors was yet another august Irish custom.

Scholars believe that monks of the Mediterranean region discovered the art of distilling spirits sometime in the 11th century. Such liquors were used as medicinals in monasteries which operated hospices to treat the sick.

Since the heady liquid seemed to have some remedial effect especially for pain, it was called aqua vitae or “water of life.” No one knows exactly when the process reached Ireland, but many theorize it was introduced by Irish clerics who had traveled abroad. When the Latin term aqua vitae was translated to Gaelic, it became uisce beatha, which in turn was eventually shortened to simply “whiskey.”

The first written record of Irish whiskey appears in the Annals of the Four Masters where it is stated that Risteard Mac Raghnaill, who had been the heir apparent to the chieftanship of Muintir Eolais, died on Christmas Day from drinking too heavily. To the entry, the scribe Mageoghagan noted wryly, “Mine author says it was not to him aqua vitae, but aqua mortis.”

Despite his lordship’s untimely demise, usque baugh continued to be used as a medical treatment for whatever might ail. Curative properties aside, Irish whiskey won most of its admirers with its superb taste, and by the time Elizabeth I ascended the throne of England, Irish whiskey was widely respected. The British writer Fynes Moryson described it thusly: “The Irish aqua vitae is also made in England, but nothing so good as that which is brought out of Ireland.” Irish whiskey of Elizabethan times was, however, not the drink we know and love today. As Moryson noted, “…the uisce beatha is preferred before our aqua vitae because of the mingling of saffron, raisin, fennel seed and other things.” Moryson was not alone.

The English were, in fact, so fond of Ireland’s whiskey that it could help a man win friends at court. In 1585, Mayor White of Waterford sent a certain Lord Burghley a girl of two bed coverings, two green mantles and a barrel of Irish.

Ireland’s English overlords noted too that Irish whiskey’s popularity posed a serious problem: the Crown was not earning any money from it and the financial potential was immense. That changed on Christmas Day, 1661. A tax of fourpence was levied on every gallon. Immediately, a new problem arose: how to find the distillers.

Used extensively for medicinal purposes, to celebrate good fortune, and to show hospitality, whiskey making remained a cottage industry for nearly 300 years, and by the 18th century there were more than 2,000 stills (mostly illegal) in the country. Realizing that huge profits were slipping through their fingers, savvy business folk launched Ireland’s whiskey industry.

Jameson, Ireland’s most important export brand, was established in 1780. The original distillery at Middleton, County Cork, which has been totally restored, is open to the public for tours that include a look at the world’s largest pot still (30,000 gallons). Bushmills, though founded four years later, holds the distinction of having been the first distillery to receive an official government license. James Power founded his distillery in 1791. Within 50 years, Powers was producing 33,000 gallons annually, and it is yet the most popular brand in Ireland.

When commercial product began appearing, the public noticed that the flavor had changed. Distillers didn’t add exotic spices. Consumers didn’t take to this new taste easily, choosing to add their own measure of lemon, cloves, nutmeg, and honey. Often the concoction was heated before serving.

Thus was born Ireland’s famous whiskey punch that even now is a favorite winter drink.

But it is the pure taste of fine Irish whiskey that most of us know and love — a taste that is distinctly different from its main competitor, Scotch whiskey. Though staunch Scots will undoubtedly argue otherwise, it is likely that the secret of distilling was carded to Scotland by Irish missionaries. Both Irish and Scotch whiskey share an identical distilling process, yet they are markedly different in flavor.

The twofold answer to this conundrum lies in the earth. After being mixed with water and left to germinate, malt (the base ingredient of both whiskeys) is dried. Though Ireland and Scotland each use turf cut from their peat bogs as a domestic fuel source, no peat is used to dry Irish malt which also occurs in a closed kiln, creating a purer flavor. The second, and perhaps even greater difference, is the water itself. In Scotland, especially the lowlands, water filters through the peat bogs and carries a heavy peaty flavor which passes on to both the malt and the whiskey. Irish water, on the other hand, filters through the island’s underlying limestone bedrock and has not even a trace of peat taste. Thus, Ireland’s whiskey is sweeter and more delicate than Scotland’s robust product.

How Scotch whiskey came to be such a strong competitor to Irish is also interesting. In the early 20th century both countries had many distilleries. Then, three things happened: America’s prohibition period, the Great Depression of the 1930’s, and Word War II. When the Prohibition Act was passed in the United States, whiskey consumption plummeted. Also, smugglers got a better deal from Scotland than Ireland and so brought in more Scotch whiskey than Irish. Both occurrences seriously hurt the Irish distillers. Then the Depression hit, and many Irish distilleries were forced into bankruptcy. But perhaps the most serious damage to the industry occurred during World War II. Ireland remained neutral to the conflict, and American troops were billetted in Britain where Scotch whiskey quickly became their favorite drink. Once the war ended and the soldiers returned home, they brought a love of Scotch with them and during the exuberant 1950’s it became one of America’s most popular spirits.

Slowly but surely, Ireland has regained a share of the whiskey market. Many of the old distilleries are reopening, some independently and some under the corporate umbrella of the two largest distillers, Bushmills and Jameson. Only a few are currently distributed in the United States (Tullamore Dew, Paddy’s and Kilbeggan), but when travelling in Ireland be on the lookout for: Tyrconnell, Coleraine, pure pot-stilled Jameson Redbreast and Green Spot, and the spectacular Bushmills single malts.

Sláinte!

Recipes

Whiskey Punch

1 ounce Irish whiskey

1 tablespoon honey

6 whole cloves

Boiling water

Slice of lemon

Pour the whiskey into a heatproof mug. Stir in the honey and whole cloves.

Fill the mug with boiling water. Squeeze in the lemon juice. Serve immediately because alcohol causes hot water to cool quickly. Makes one serving.

Whiskey Sauce

1 cup fine curd cottage cheese

1/2 cup Irish whiskey

4 tablespoons honey

1 cup heavy cream

Place the cottage cheese in a blender and whirl until smooth. In a small saucepan, bring the whiskey and honey to a boil. Remove from the heat and stir in the cream. Cool to room temperature, then add the whiskey mixture to the cottage cheese a little at a time, being sure to blend it in thoroughly with each addition. Makes 2 cups.

Recipe: In an Irish Country Kitchen, by Clare Connery.

Leave a Reply